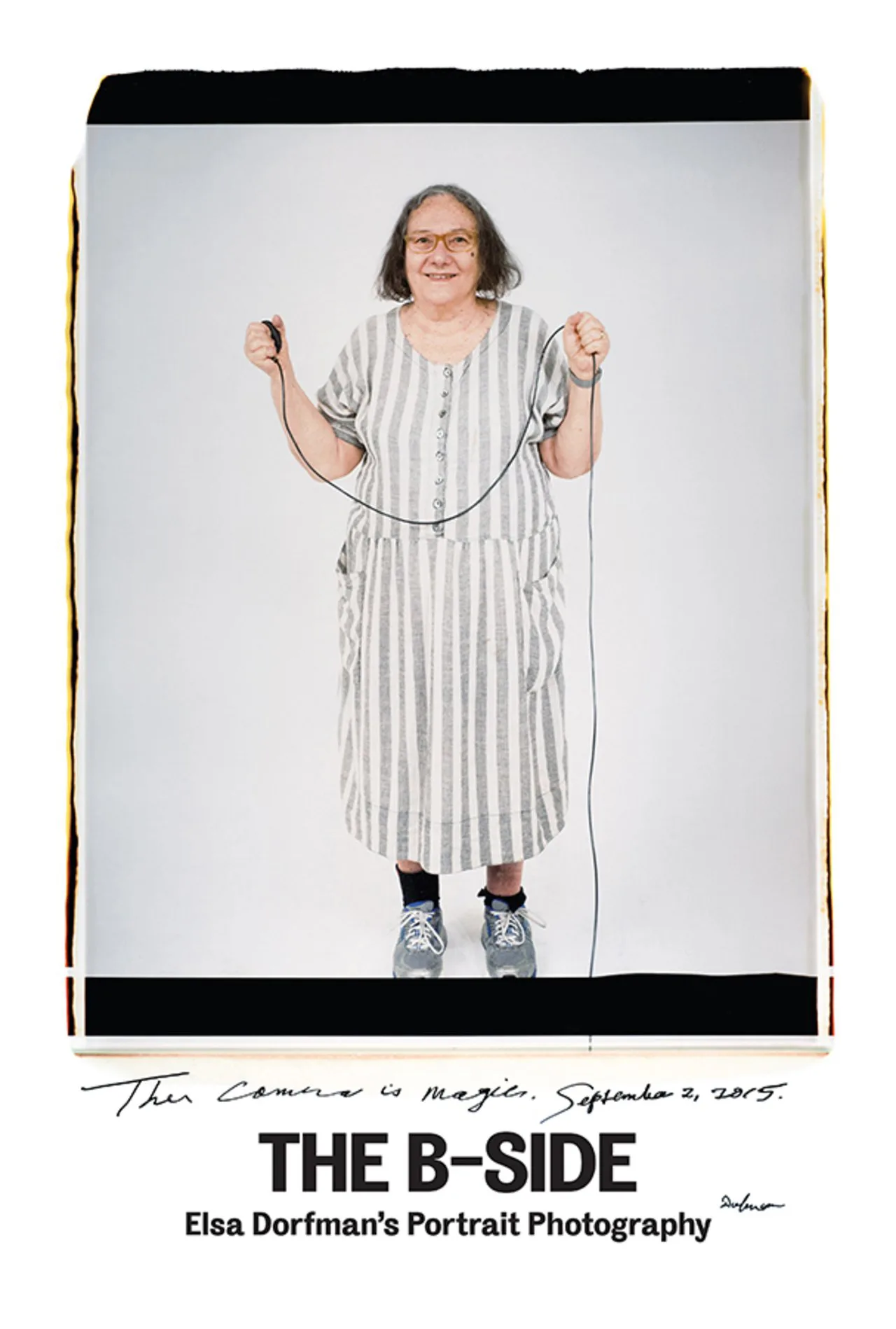

Errol Morris’ documentary “The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography” is a sideline glimpse of mid-twentieth century literary history, told partly through the lens of its title character, a photographer whose most notable work was done on large-format Polaroid film. It’s also an affecting account of the friendship and mutual respect between artists (Morris has known Dorfman for decades) as well as a fine-grained (no photography pun intended) look at the way that the development of an artist’s style is usually intertwined with the technology and materials that she chooses to embrace.

Dorfman, a Cambridge, Mass. native, started shooting literary figures after a brief stint at New York City’s Grove Press, home of many writers of the Beat generation. After moving back home, Dorfman called herself “The Paterson Society” and began organizing readings for Grove writers. In the early 1960s, she got a job at the Educational Development Corporation in Cambridge where her supervisor George Cope put a camera in her hand and told her to start taking pictures. She was a natural. As she moved through the next couple of decades, honing her art while also getting married and having a son, she took pictures of some of the most significant literary and artistic figures of mid-twentieth century America.

If you’re interested in that period, the sheer number of notable photos shown here is reason enough to see the movie. Besides Dorfman’s friend Allan Ginsberg, whose death is movingly recollected by Dorfman with the aid of old answering machine messages, we see photographs of writers Anais Nin, Audre Lorde, Anne Sexton, Jorge Luis Borges, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and musicians Jonathan Richman, Steven Tyler and Bob Dylan (whose first appearance is heralded by shots of the singer as seen from the back—Dylan’s slender, hatted silhouette is so unique that you know right away whose face you’re about to see).

Except for Ginsberg and, briefly, Dylan, none of these people are examined in any detail. We often don’t know if any of them meant anything to Dorfman personally, beyond the fact that she took their pictures. Intriguingly or frustratingly, depending on what you want from “The B-Side,” it’s just not that kind of movie. Dorfman and Morris concentrate mainly on what sort of camera and film were used during the shoot. We get a few of the usual anchoring details, such as when and where the pictures were taken and how they fit into the photographer’s life at that point, but not too many.

The film becomes more special in its final third, when Morris’ attention shifts mainly to non-famous people whose portraits were taken by Dorfman: individuals, couples, extended families, none well-known or connected to the arts. But here, too, we don’t get a lot of contextualizing information about the subjects of the pictures (much less names or dates).

Morris is mainly interested in situating the work within the timeline of his subject’s life. The balance between personal and technical detail is a bit fuzzy at times, though. We can sense Morris’ enthusiasm for the subject, but it doesn’t always translate into a film where you feel as if you’re really inside of the world he’s showing you, understanding it on an emotional as well as technical level. Photography gearheads are going to love this movie, and there are points where they would appear to be the film’s primary audience, though Dorfman does such a good job of explaining what photographic chemicals do to paper and to the image itself that if she had her own YouTube Channel where she did nothing but talk about cameras and developing, I’d watch it.

The deeper Morris has gotten into his career, the more he’s focused on notions of truth and fiction as they relate to the image. There are sections of his films where it feels as if you’re inside the mind of a brilliant college professor with an eye for beauty, seeing the images that flash through his mind as he ponders the deeper meaning of the material he’s arranging into a story—or more accurately, a portrait. Many of Morris’ best known films are, in fact, partly or mainly portraits, ones that aren’t meant to be strictly representational, but rather glimpses of the person that Morris sees when he thinks about the meaning of his subject’s life and perhaps his own, too.

This is a more laid back, at times almost free-form-seeming feature than we’re used to seeing from Morris, the restless mind behind such seminal nonfiction movies as “Gates of Heaven,” “Vernon, Florida,” “The Thin Blue Line,” “Fast, Cheap and Out of Control,” “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. MacNamara,” and “The Unknown Known” (about former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld). Morris’ decision to shoot the movie in the super-wide CinemaScope ratio, often through skewed or just counter-intuitive angles, results in some abstracted moments where we might prefer a plainer approach that makes us feel more personally connected to Dorfman. There are also quite a few awkwardly framed images (particularly when he crops into old home movie images that were originally square), which is not a complaint I ever expected to make about a film by Morris, who is so attentive to light and framing that he’s occasionally accused of being too fussy. Paul Leonard-Morgan’s score comes across as a lighter, sweeter version of the hypnotic scores that Philip Glass has done for Morris, but there’s so much of it that it can feel coercive, as if you’re being prodded to feel the way you’d probably feel anyway. As much as I like “The B-Side,” there were moments where I wanted the the more hardcore intellectual Morris, the philosopher-ethicist-explainer, to tell this story, instead of Morris the pal.

Still, Dorfman is so charming and her work so rich that none of that is a deal breaker. The movie’s modesty and brevity are rare in current nonfiction cinema. The title is a reference to the sorts of pictures that Dorfman is showing us: ones that her subjects or patrons decided not to buy or take home, for whatever reason. It’s a reference to the so-called b-sides of singles, where musicians put songs they liked but that no one expected to be hits. The quality of Dorfman’s work is so high that it’s hard to tell why the pictures that got left behind were considered less good than the ones that were taken home. Sometimes even Dorfman doesn’t know. This movie is itself a b-side. It might be interesting to see it as part of a double-feature with “Vernon, Florida” or “Gates of Heaven,” which are filled with the sorts of people that Dorfman shot when she wasn’t photographing the titans of the arts.