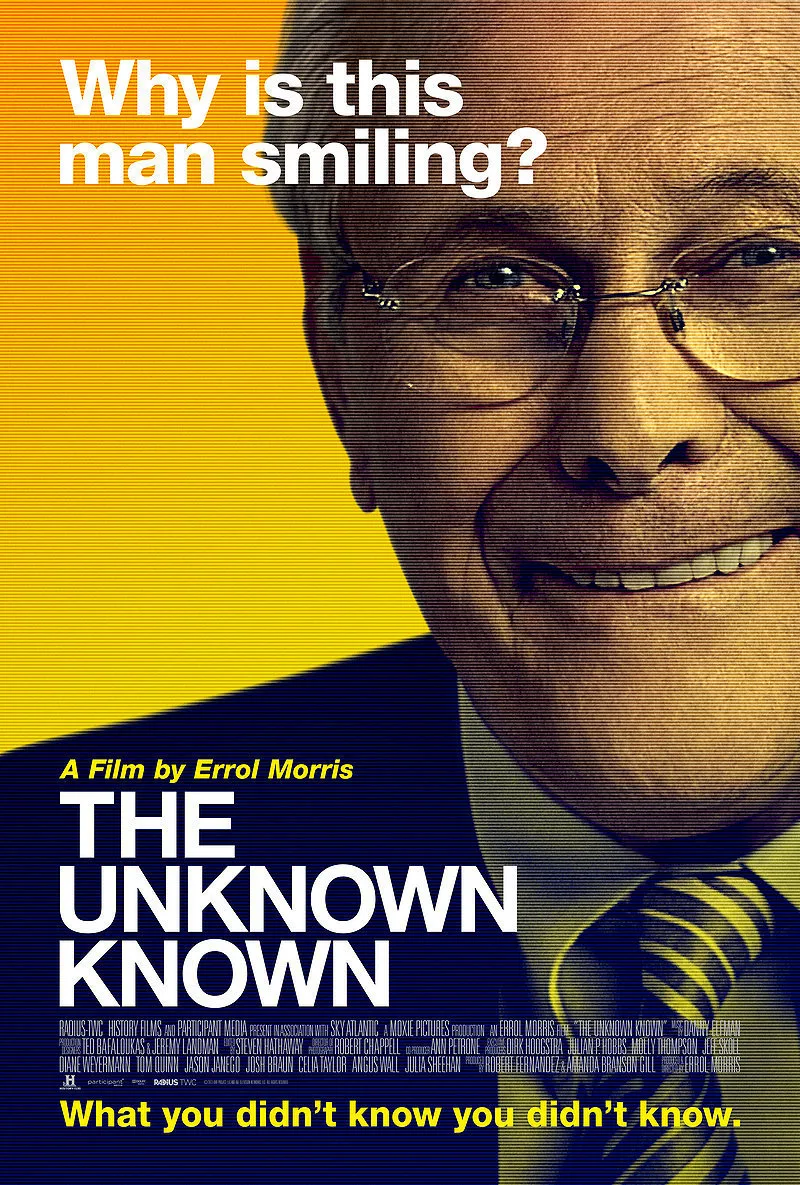

In 2003, documentary stalwart Errol Morris released his celebrated, Oscar-winning portrait of Vietnam-era U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, “The Fog of War.” This week brings the release of what’s effectively a companion piece to that work, a portrait of Iraq War SecDef Donald Rumsfeld, a film that perhaps would have most accurately been titled “The Fog of Words.”

That it is called instead “The Unknown Known” shows why: the expression is an infinitesimal speck in the cyclone of verbiage that almost visibly circles Rumsfeld’s head at every moment, like moons whirling around Jupiter. The grinning politico famously split verbal hairs by enunciating the differences between known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns and unknown knowns—pettifogging distinctions that needn’t be rehearsed here. Suffice it to say that, somewhat bizarrely, Rumsfeld seems to spend more time talking about words than the things they refer to, a characteristic that can make Morris’ film feel stubbornly frustrating.

At first glance, that is. More than any film this reviewer has seen in ages, “The Unknown Known” richly rewards a second viewing. The first time through, it’s all too easy to focus on the many issues Rumsfeld’s verbal miasma obscures rather than reveals, and to fault Morris for not pressing and pinning down his subject more effectively. The second time, one can’t help but reflect that these bafflements are what the film ends up being about, really, and that they may be a more worthy and fascinating subject than the officious man who generates them.

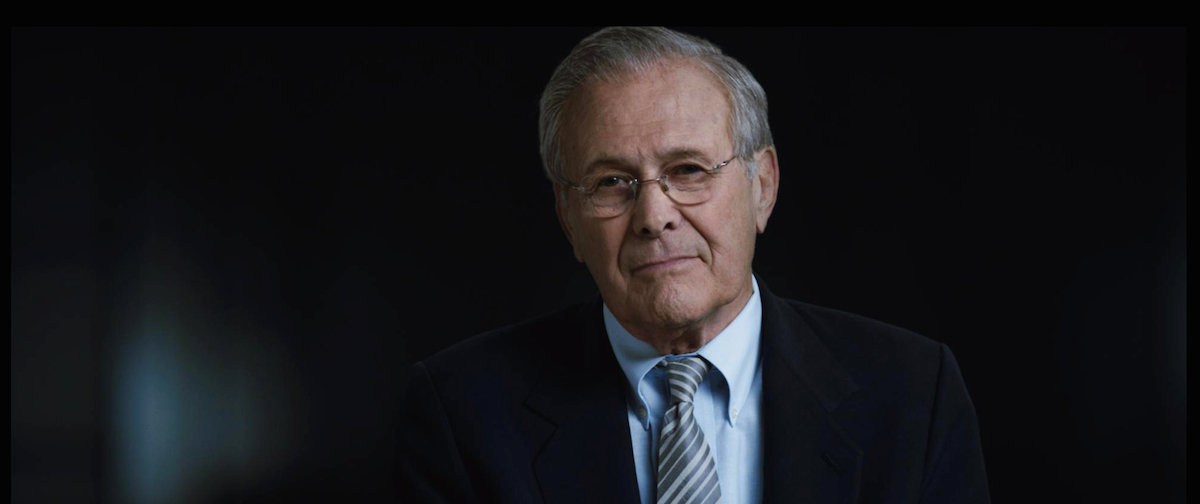

Morris certainly knows his film isn’t going to give many viewers what they will be hoping to find in it. In the first part of “The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld,” a verbose but worthwhile four-part essay recently published in the New York Times, he notes, “When I first met Donald Rumsfeld in his offices in Washington, D.C., one of the things I said to him was that if we could provide an answer to the American public about why we went to war in Iraq, we would be rendering an important service. He agreed. Unfortunately, after having spent 33 hours over the course of a year interviewing Mr. Rumsfeld, I fear I know less about the origins of the Iraq war than when I started. A question presents itself: How could that be? How could I know less rather than more?”

Indeed, “Why were we in Iraq?” will be uppermost among the questions people carry into the film, and like Morris, many viewers may well come out with the weird feeling that they know less than when they went in. It is also possible to see in this a degree of failure on Morris’ part, a sense that he might have channeled his inner Mike Wallace to fashion a more aggressively incisive interrogation of Rumsfeld.

Yet it’s not as if Rumsfeld is deliberately stonewalling the filmmaker, at least in any conventional sense. You feel like he thinks he’s being perfectly candid and forthcoming, or even better: all these zealously mined and minted words, all the trips to the Pentagon dictionary to nail down their meanings as precisely as possible, all the tens of thousands of memos he once spewed out and can now revisit at will – this colossal outpouring must add up to something of monumental significance and clarifying value, mustn’t it?

Well, no. Not here. The more precise and articulate Rumsfeld becomes, the more we lose the thread. It’s as if he’s spent his life generating a brilliant smokescreen that has ended up swallowing and suffocating precisely what it was meant to protect: the truth.

Morris’ film deploys all his trademark high-end mannerisms – lush Danny Elfman score, pristine cinematography, selective newsreel footage, dreamy slo-mo views of abstracted land- and seascapes – and its narrative covers more than just its subject’s turns as SecDef. After hearing Rumsfeld’s recollections of 9/11 (he was in the Pentagon when it was hit) and the lead-up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq (he learned about it by hearing Dick Cheney inform Saudi Prince Bandar!), Morris turns back to trace his political rise.

Elected to Congress at the tender age of 30, he was brought into the executive branch by the Nixon White House. Yet because Nixon’s inner circle mistrusted him (Kissinger thought he was too cozy with the New York Times and Washington Post), he was sent abroad and thus escaped being a casualty of Watergate. Under Gerald Ford he served as White House Chief of Staff and then the nation’s youngest SecDef. For a moment it looked like he might be Ronald Reagan’s running mate, which could have propelled him toward the Presidency itself, the trajectory eventually taken by the first George Bush, his rival in the Republican ranks. After serving corporate interests for a couple of decades (a subject Morris doesn’t explore at all, unfortunately), he returned to public life under the second President Bush, eerily declaring that he didn’t want to preside over the post-mortem of another Pearl Harbor, which he ascribed to a “failure of imagination” in the nation’s defense establishment.

His memories of all of this are curiously impersonal. You never hear him describe or say he liked somebody, and it’s easy to believe that nobody much liked him. He sometimes notes odd details (President Ford bumped his head, Chevy Chase-like, not long before Sarah Jane Moore tried to kill him), but never discusses ideas or principles. The consummate Republican apparatchik, he’s a good soldier whose chief virtue lies in never questioning his orders, though he constantly fusses over the words they contain.

He seems impervious to the irony that he presided over a Pearl Harbor-like failure of imagination (i.e., intelligence and its analysis) not once but twice: in not anticipating al-Qaeda’s attack on 9/11, and in not seeing that Saddam Hussein had no weapons of mass destruction, which sparked a war that killed tens of thousands of people. How could this have happened? How could Colin Powell have declaimed such bald-faced misinformation to the United Nations? “I think he believed it,” Rumseld blandly intones. When all is said and done, was American right to invade Iraq? “Time will tell,” he shrugs.

You might think that such failures, ones that cost so many innocent lives and (in the case of the war) trillions of dollars that America could ill afford, might provoke a little soul-searching. But here it’s tempting to conclude that there’s not much of a soul to search. Rumsfeld gets teary-eyed once, recalling a wounded U.S. soldier he saw in Walter Reed hospital, but there’s no guilt in his self-analysis, and the only shame is connected to the photos of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, which caused him to resign not once but twice. (Bush refused those requests, but later fired him.)

“The Fog of War” and “The Unknown Known” are a strikingly matched pair, one a modernist masterpiece, the other dizzyingly post-modern. Robert McNamara’s testimony in the first film offers the satisfactions of a genuinely deep and penetrating self-analysis, and that’s obviously because he came from a world where there were clear distinctions between right and wrong, good and bad, success and failure – words that at one time actually meant something and had real personal consequences. Rumsfeld in contrast belongs to a world in which there is no real accountability, either public or private, in large part because words can be bent to mean anything, or nothing. The proof of this in “The Unknown Known” amounts to a valuable if tremendously damning commentary on our current political culture.

Morris dedicates his film to the memory of Roger Ebert, an early champion of his work.