“Starbuck” is one of those high-concept yet formulaic, sitcom-like comedies that gets by on charm and speed. It is manipulative and ingratiating ut totally worth your time if you manage to pass one crucial test: Does French-Canadian actor Patrick Huard’s smile make you happy? For me, the answer is yes.

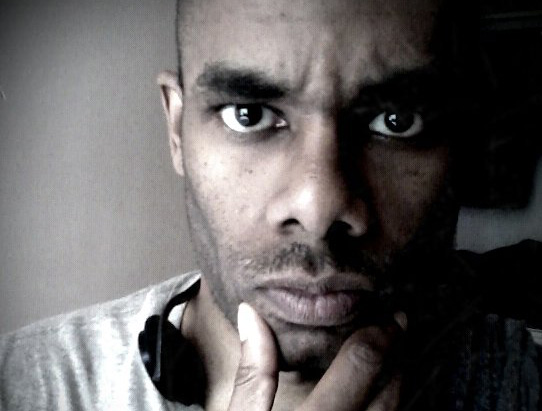

Huard reminds me of something director Paul Thomas Anderson once said about John C. Reilly, that the mere sight of his longtime collaborator — that genial, rubbery Reilly mug — makes him smile. Comparisons tend to cheapen things, but what the hell: Mash up Francois Truffaut, Daniel Auteuil and Judd Nelson, and you get Huard’s homely/handsome/comical face. It’s those kind Truffaut eyes, radiating warmth and passionate concern, that sell this movie’s humanist spirit, despite its lack of bite or great surprises.

Huard plays David, a perpetual screw-up in his early 40’s who finds out he is the father of 533 children. See, when he was a young slacker, he made tons of quick cash as a sperm donor—over 600 times. Since he used an alias, Starbuck, 142 of his now-adult offspring are filing a class-action lawsuit to get the sperm bank to divulge their father’s true identity.

The suit couldn’t come at a worse time for David, who is ducking violent loan sharks he owes bigtime, whose girlfriend is pregnant and whose job delivering meat for his father’s butcher shop is always imperiled by his complete incompetence. Yep, it’s one of those movies, the kind of reality-flavored comic fluff Ho’wood once factory-milled for “SNL” alumni every few months, before Judd Apatow took over the market last decade, adding a bigger dash of improvisatory salt.

David emerges as a character who has has been outlawed in movies, a lovable guileless fuckup. The fashion in popular films has been more along the lines of “As Good As It Gets“-through-“Silver Linings Playbook,” where the hero who starts off sour and mentally unstable ends up sloughing off the traumas and disappointments that made him so.

“Starbuck” is interesting mainly because of its investment in a character who doesn’t have to be mean to be interesting. David knows what love is, and that’s his problem. He seems to have no concept of time or self-preservation once he gets absorbed in the work of helping somebody whose plight has touched his heart.

Screenwriters Ken Scott and Martin Petit take the safest route through these familiar situations, but director Scott’s dynamic staging and tendency to let Huard carry the scenes with screwball aplomb keep us focused on David’s universal predicament. Any single man who has found himself suddenly facing the prospect of fatherhood should relate. David’s girlfriend knows nothing of his secret Starbuck identity but assumes that he is unfit to raise the one child she knows he’s fathered: hers. Unaccomplished and aimless at 42, he seems, in her estimation, certain to go along with her plan to raise the child alone.

Contrived as it is, the long midsection of the film covering David’s awakening to the glories of fatherhood is often unavoidably profound and moving. He gets a dossier containing the identities of all his adult children and goes snooping into their lives. Each stock “messy” situation (the drug addict, the dour goth kid, the disabled kid) and proud moment (David discovering he’s fathered a soccer star, a musician, an actor and a lifeguard) plays out with all the hugging and learning you’d expect from pre-Larry David television dramedy.

Yet I found myself awash in the same awkward emotion that accompanied the end of “Saving Private Ryan.” Remember when elderly Ryan had a heart-to-heart at the grave of the man who saved his life back in WWII? The mob of descendants lined up behind him in soft focus? It was so transparently mawkish, what Steven Spielberg was up to in that scene, and yet it was so devastatingly powerful. All those generations of Ryans who simply wouldn’t be if not for an unfathomable chain of events — but also if not for a few clear, moral, compassionate decisions made in faith.

“Starbuck” has several moments like that, and they are honest ones. Forget about the silly plot; it’s all in the eyes.