“Speak No Evil” is a throwback to the 1980s-’90s era of medium-budget thrillers like “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle,” “Unlawful Entry,” and “Fatal Attraction,” in which representatives of supposedly respectable bourgeoisie society were menaced by dangerous outsiders who smelled weakness in them and/or wanted to punish them for their sins, perceived or real.

As written and directed by James Watkins (“The Woman in Black”), adapting a much bleaker but same-titled Danish original, it’s a fun audience movie, best enjoyed on a Friday or Saturday night in a packed theater where shouting, “Get out of there, you dummy!” at the screen is not only tolerated but expected. The movie might also be of interest to therapists who tell their patients that they need to listen to that inner voice that tells them they need to leave an abusive relationship and not let themselves get talked into staying. There are a lot of teachable moments here, some involving homemade weapons.

The main characters are a family from the United States who relocated to London for professional and personal reasons but have fallen on hard times. Husband Ben Dalton (Scoot McNairy), wife Louise Dalton (Mackenzie Davis), and middle school-aged daughter Agnes (Alix West Lefler) are further traumatized by a betrayal within the family, whose details will eventually be disclosed once the Daltons get themselves into a pressure cooker situation.

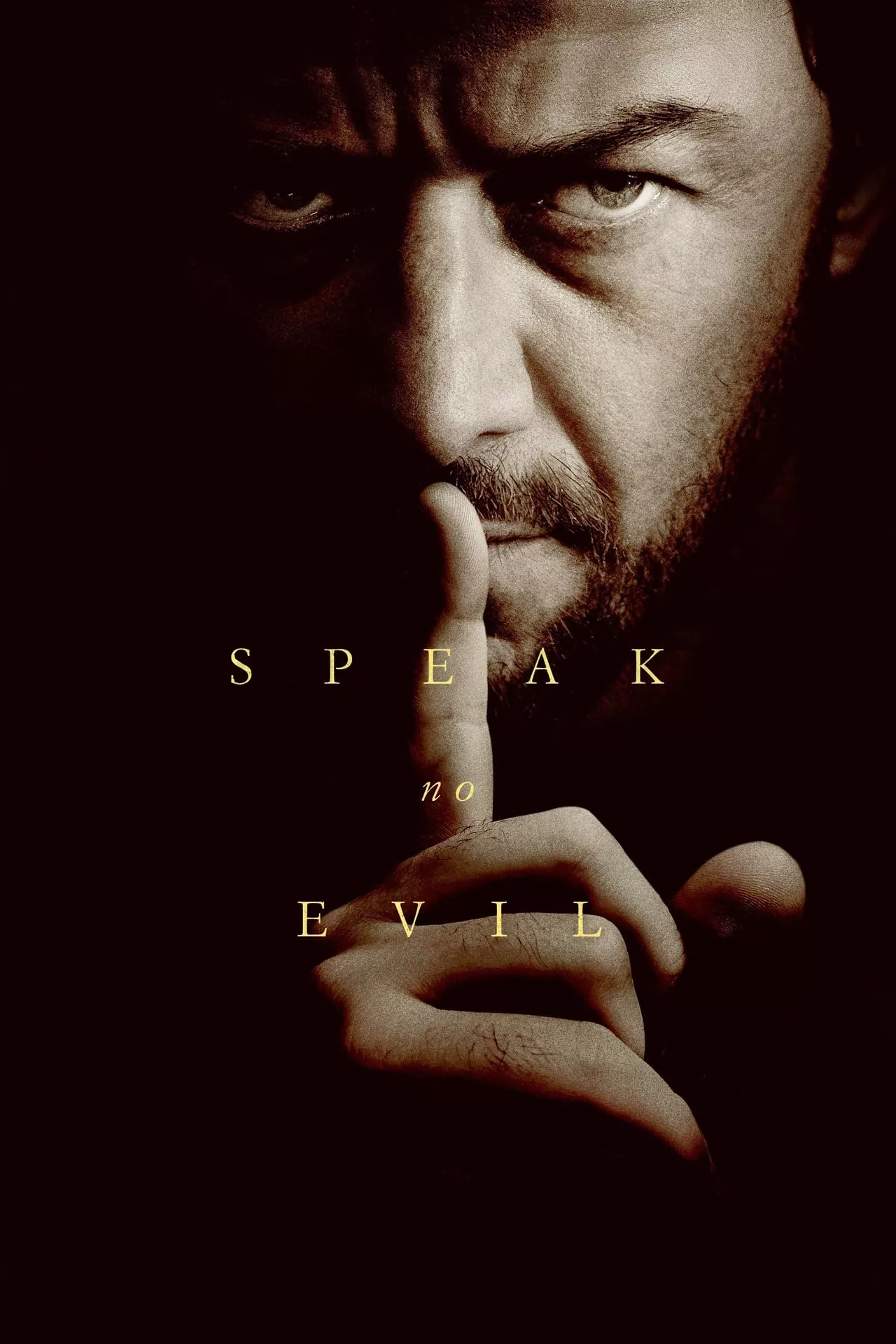

That would be the unexpected and insinuating arrival of another family, consisting of a fortysomething father and physician named Paddy (James McAvoy), his much younger, Eastern European wife Ciara (Aisling Franciosi), and their son Ant (Dan Hough), who’s about Agnes’ age but can’t speak clearly due to what Paddy describes as a birth deformity of the tongue. The families meet on vacation in Italy and make enough of a connection for Paddy to invite the Daltons to his spacious but somewhat decrepit old house in the countryside a few hours outside London. They’re supposedly going to hang out and enjoy home-cooked meals and go swimming in the local pond and walk in the woods and do lots of other things that sound like fun until you figure out that your hosts are scarily unhinged, which happens more quickly than you might have expected.

It’s here that the audience’s tolerance of stupid behavior will begin to vary and manifest itself in hooting and hollering. There are a lot of points in the movie where the Daltons could conceivably look at some social infraction or another, whether it’s Paddy insisting that the avowed vegetarian Louise takes a bite of slow-roasted goose or Ciara pretending to go down on him at a dinner table for shock effect and announce, “Oh, my goodness, look at the time!” and get as far away from these people as possible. Part of the fun here, if it’s your cup of tea, is watching the Daltons talk themselves into remaining in a bad situation or returning to it after having left, each time digging themselves deeper into a hole that could eventually swallow them up.

As mentioned, “Speak No Evil” is based on a 2022 Danish film by Christian and Mads Tafdrup. Not too many people saw it, but if you did, you may be irritated by what’s been done with it. The result borders on those behind-the-scenes stories (often attached to the production of ‘80s and ‘90s thrillers, interestingly) where filmmakers ended a tale in a perfect but upsetting or even horrific way, but test screening audiences rebelled and demanded that the bad people be punished violently, whereupon a new ending was shot and the movie made a ton of money and everyone went away feeling like the right decision had been made because their bank accounts were fattened. Aficionados of imported art-house psychological horror may even look at the original “Speak No Evil” and the remake and be reminded of a similar situation from over thirty years ago, when the masterfully bleak 1988 Dutch film “The Vanishing,” aka “Spoorloos,” was remade by its own director for an American studio and given a much happier ending.

The original “Speak No Evil” was mostly acclaimed, deservedly so, but only made about a third of its budget back at the box office, probably because it had one of those endings that was thematically right but made you want to go straight home and crawl into bed and stay there for two days. Watkins’ adaptation follows the original pretty closely except for the ending, which is considerably longer and gives the Daltons a chance to work through the specific problems that brought their family to the brink of collapse and do it while fending off their hosts with guns, cleaning supplies, hammers and such.

Most thrillers of this type end with a small number of people battling for their lives in a dark house. “Speak No Evil” embraces that cliche with gusto. Here, too, you can appreciate it as an audience picture. I laughed a lot with (and sometimes at) the movie, mainly when Watkins was turning the movie into an inverted version of another English countryside thriller “Straw Dogs.” Davis’s intensely physical performance revs into high gear during this section. She and McNairy have some wonderful nonverbal exchanges where wife and husband look at each other, and you can intuit a whole hour’s worth of marriage counseling notes.

The performances are all superb, bordering on impeccable. It helps that three of the four leads (McAvoy, McNairy, and Davis) have previously played characters who are somewhat similar to this, if only in terms of their plot functions; you know immediately that you’re in good hands with these actors, and that they’ll find subtle colorations in a situation that you knew can really only end in one way.

McAvoy, in particular, makes a powerful impression. He has slowly but surely turned into a kind of movie star over the decades, and he brings his wicked yet subtle charisma to bear here, at times in a way that may remind viewers of an early performance by Russell Crowe, where you couldn’t immediately be sure if you were seeing a hale-and-hearty bloke’s-bloke who was a bit rough around the edges but fundamentally decent or a monster. Paddy’s both. His warmth, insecurity, extreme sensitivity to perceived disrespect, and ostentatiously acted-out demonstrations of love for his wife and child seem absolutely sincere, but there’s always a lurking subtext that undercuts any possibility that the film is excusing or glamorizing him: it knows that some of the worst people who ever lived love their families, or say they do. Davis and McNairy and, to a lesser extent, Franciosi (only because her character is comparatively underwritten) act as support and/or foils for McAvoy’s grinning jack-in-the-box energy.

As for the film’s tendency to keep giving the Daltons an “out” and then having them somehow end up back in that drafty old house, telling themselves they’re doing the right thing, well: that’s also what happens in an abusive relationship. The movie’s very structure mimics that cycle. I don’t know if that’s enough to dissuade people from complaining that these folks had a dozen opportunities to get out of there permanently and never took them; it didn’t quite work on me, honestly. But I think it’s a conscious choice on the part of the movie, and worth bearing in mind as you argue about its merits and drawbacks.

See this one opening weekend.