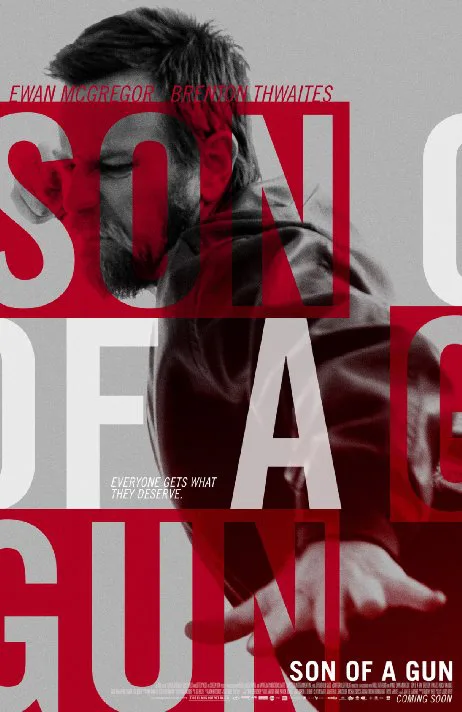

The release of a Michael Mann film has evidently become such a cinephile event that A24 pushed the release of Julius Avery’s Mann-influenced crime thriller “Son of a Gun” until after the similarly delayed “Blackhat” was finally granted a release. It’s not hard to see why they were waiting for “Blackhat” to lead by example, “Son of a Gun” is a not quite fish, nor entirely fowl. Entering a cycle of Australian neo-noir that includes the likes of “The Square,” “Snowtown” and “Animal Kingdom,” Avery sets himself apart by piling on the hardware and fireworks, but what really keeps things interesting is the novelty of watching generic convention cut with a quiet reverence for the human beings shooting it out with the police. The break-neck momentum and gangster film shorthand make it difficult to think too long about what’s happening, forcing you instead to wonder who, why and how.

Big-eyed Brenton Thwaites plays JR, introduced having his shaggy hair cut off by prison barbers. Before he’s even made it to his cell, he’s begun looking around for a way up the ladder. He doesn’t want to be scared anymore and impressing the imposing Brendan (Ewan McGregor) looks to be a quick way out of the dark. As usual, that means taking on a few new responsibilities. Soon he’s breaking Brendan and his gang out of jail via stolen helicopter and helping them plan a gold heist. But “soon” is frankly putting it a little too mildly. Avery books it through the first act, most interested in the relentlessness of the criminal lifestyle, a road that Brendan has to be pave as he drives on it. The film mimics the rush felt by its young hero by only living in the moments that get his heart rate up (heists, prison brawls, getting a peak into the decadent lifestyle enjoyed by kingpins), but it keeps its theatrics uncharacteristically muted. That means no slow-mo, no fourth-wall breaking & music only when a change in dynamic needs to be ushered in (Aside: there needs to be a moratorium on using Bon Iver on movie soundtracks yesterday). The action speaks for itself. Avery just wants to know what’s really at the end of the rainbow for these guys, and that means being honest about every step they take. Ambition is a drug for which crooks are still figuring out the proper dosage.

The Mann-influence is heavy as a bag of bricks, from the carefully choreographed gunfights to the quickness with which a simple fight can become unbearably ugly. The film plays like a kind of mash-up of “Heat” and “Thief,” with their tales of men on the wrong side of the law, fighting purposelessness by weighing the next big score against an escape into domesticity. The sense that the world has a lid on it that tightens with every bullet is straight out of Mann. There’s even a crib from Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Le Deuxième Souffle,” one of Mann’s stylistic ancestors. Of course, there is no duplicating Mann’s singularly charismatic images and rhythms, so the film feels like a lightweight coming out in the wake of “Blackhat.” Avery’s more than capable behind the camera, he just needs to be met halfway by his screenwriting, which dwells in overly familiar territory.

There’s an anarchist’s cookbook tactility to Brendan’s scheming that takes you by surprise. You believe that JR’s insane prison break could work because Avery connects the dots so thoroughly. It makes all the madness much less difficult to believe when you’ve witnessed every step of the planning in as sober a fashion as possible. Thwaites shines whenever JR has to bluff his way through endless meetings with every breed of lowlife in Australia. He’s constantly in over his head (a scene of him following the femme fatale into the ocean is a bit on the nose), and he has to recalibrate his version of real every few minutes. There’s a shot of Thwaites staring agog at Damon Herriman, playing a mulleted meth-head arms dealer, that’s priceless. JR tries and fails to look unfazed in the face of the wild action movie going on around him. His pretty, expressive face betrays him when he needs it most. Though frankly, he’s got nothing on the pulchritude of his co-stars.

McGregor’s unfairly pleasing visage is used to great effect as a mask for Brendan’s insanity. McGregor has never been allowed to play dangerous and he attacks the part with palpable delight. His mood swings are just controlled enough to be utterly believable and a little terrifying; his cool sadism keeps JR in check and in thrall. Alicia Vikander, channelling Eva Green, is the moll who naturally represents as big a risk to JR’s future as a heist. Both are given the character equivalent of thrift-store suits, and they model them like Loulou de la Falaise. They play the hell out of their roles and clearly have fun doing it. Which isn’t to say that Thwaites isn’t a solid center. Those big, beautiful eyes reveal untold depths whenever they witness death. Whether he’s watching his cell-mate bleed from a self-inflicted wound or holding a gunshot man as he breathes his last breath, Avery gives a glimpse of Thwaites’ dark pupils, and we understand more about JR than any of his dialogue can tell us. There’s a horror and truth that comes from staring into the abyss, and “Son of a Gun“ could stand to learn a little more from Michael Mann about how to convey those cinematically. It’s a little heavy on incident, and a little light on soul.