“I don’t want life to imitate art. I want life to be art.”—Suzanne Vale (Meryl Streep) in Mike Nichols’ “Postcards from the Edge”

This indelible quote, originally attributed to Austrian writer Ernst Fischer, was further immortalized by Carrie Fisher in her brilliant script for the aforementioned 1990 comedy, adapted from her semi-autobiographical novel. Battling a cocktail of drug addiction, bipolar disorder and industry sexism, Fisher allowed her experiences to inform her art in ways that were exhilaratingly cathartic. I was lucky enough to catch her one-woman show, “Wishful Drinking,” onstage in 2010, where she earned guffaws by sharing stories of unvarnished honesty laced with biting wit. She often said that if her life weren’t funny “it would just be true, and that is unacceptable.”

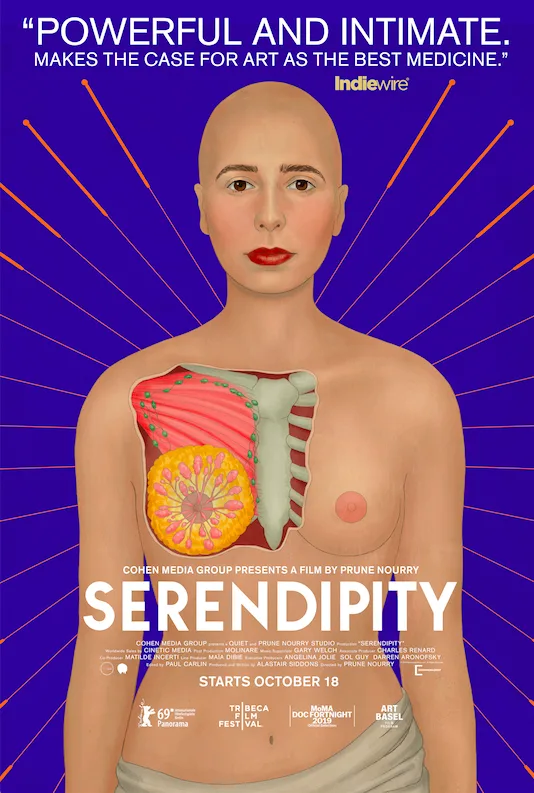

I am reminded of her resilient spirit every time I see creative souls transcend their challenging circumstances by being proactive about them, finding the value in what could so easily be deemed a paralyzing setback. Prune Nourry, the subject and director of the new documentary, “Serendipity,” is an inspirational figure not unlike Fisher, whose life caught up with her art to a point where they became practically indiscernible from one another. Though a great deal of her epically mounted, self-funded creations are on display here, it is her body that is treated as the central artwork.

Born in France and working as an artist in residence at Brooklyn’s Invisible Dog Art Center since 2011, Nourry was only 31 when a tumor was found in her right breast during a routine gynecology appointment. It was Darren Aronofsky, who joins Angelina Jolie as an executive producer, who suggested that Nourry document every step of her journey. In the opening shot, we follow the filmmaker’s long trip up to her hospital room from the perspective of her eyes as she lies on a stretcher. There are echoes here of the innovative first person POV angles in Julian Schnabel’s “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” which also happened to be the work of a director skilled in fine art.

What’s most striking about these early sequences is the surrealistic approach to sound design by a team that included the late Max Bygraves, to whom the film is dedicated. When Nourry films her gynecologist as he places a camera inside of her, the sound evokes the deep sea submersion of oceanographers aboard a vessel. The moment is viscerally intimate without becoming explicit. Nourry never has to show the scars left by her mastectomy in order to convey the pain of having lost an organ synonymous with femininity. How ironic that an artist preoccupied with female biology and fertility would suddenly find herself freezing her eggs prior to enduring chemotherapy.

Just because cancer has disrupted her previous plans for a documentary on her work doesn’t mean she feels any need to switch the camera off. Soon after we see Nourry carefully carving the lines of hair on an enormous sculpted head, the film cuts to a shot of her shaving her own head in profile, moving her hands with the same meditative precision. The first images following the film’s title card were lensed by French New Wave goddess Agnès Varda, who succumbed to cancer this past March at age 90. Dubbing the dearly departed genius as “her sweet potato” in the credits, Nourry invites Varda to film the removal of her braid, and couldn’t have picked a better friend to lighten her spirits.

“It makes a lovely sound,” Varda observes as Nourry severs the hair with scissors before placing the trunk-like appendage in her mouth, thus creating a comical new artwork. Exuding the same joie de vivre she displayed while dancing with Jolie at the Governors Awards, Varda recalls how some of the mythological Amazons were known to remove a breast in order to better shoot with an arrow. This observation is vividly etched in The Amazon, the gorgeous 12-foot-tall sculpture Nourry unveils in 2018. It takes the form of a female warrior covered on one half of her body with acupuncture needles made out of incense sticks, which give off a healing glow when lit.

Nourry’s belief in how everything connects has been demonstrated time and again throughout her career, with her uncannily prescient work taking on newfound meaning in light of her 2016 diagnosis. Just two years prior, the artist made similar use of incense sticks in her installation “Imbalance,” covering fragmented bodies evoking the Bamiyan Buddhas destroyed by the Taliban six months before 9/11. In an all-too-brief snippet, Nourry explains to an onlooker how this act triggered the modern rise of extremism, and that her work is meant to serve as a symbolic remedy. Her commentaries have frequently proven to be amusing in years past, such as 2011’s “Spermbar,” in which a NYC food cart was transformed into a sperm bank, and 2009’s “Procreative Dinners,” where participants feasted on courses mirroring the stages of medically assisted childbirth, including a cast of Nourry’s own nipple in almond paste (animator Quentin Bailleux lends a welcome playfulness to this segment).

One of Nourry’s earliest art creations, “Fertility,” fused a woman’s breast with the udder of a cow, foreshadowing the human/animal hybrids she sculpted for her provocative trilogy on gender preference. Its first installment was “Holy Daughters,” illuminating India’s hypocritical treatment of girls as disposable beings and cows as sacred symbols of fertility. A towering iteration of Nourry’s women-cow deity was tossed into the Ganges for “Holy River,” just as the statues of 108 schoolgirls were buried at an undisclosed location in China for the culminating portion, “Terracotta Daughters.” This homage to the Terracotta Army—sculpted to protect the late Emperor Qin Shi Huang—serves as a poignant tribute to the girls robbed of life as a result of China’s one-child policy causing families to favor sons. As impactful as this footage is, it likely would’ve been a better fit for Nanfu Wang’s “One Child Nation,” seeing as it was originally filmed for the director’s scrapped feature.

It wasn’t until a good deal of post-screening research and contemplation that I was able to fully grasp the intention and nuance of many works featured here, which are presented with minimal context in order to awaken one’s intuition. This can make for a challenging viewing experience at times, but I ultimately found it to be a rewarding one. I absorbed “Serendipity” as I would the marvels at an art museum, in a state of hushed awe. As Nourry juxtaposes the reshaping of her body post-surgery with the sculpting of The Amazon, we understand with newfound clarity how her process of molding each creation has helped her reach a place of acceptance regarding her own evolving physicality. If art and religion are indeed parallel lines, as noted by the Dutch theologian in Paul Schrader’s Transcendental Cinema, aiming to find meaning in life’s patterns, then Nourry has provided attentive audiences with nothing less than a spiritual experience.