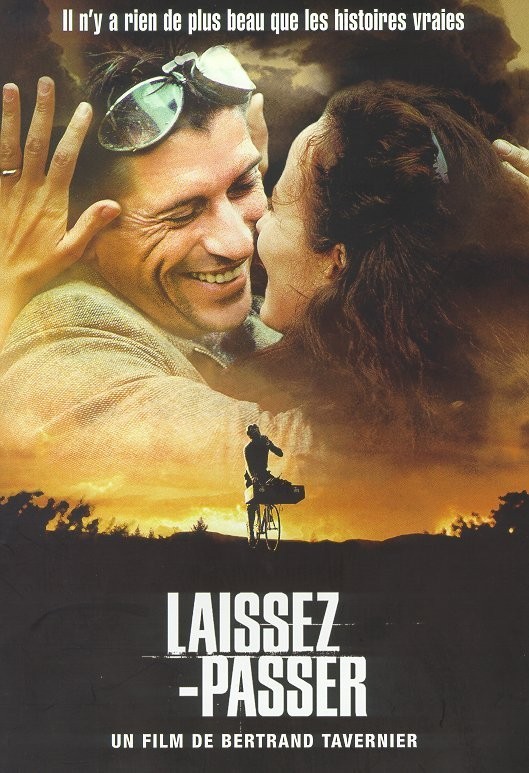

More than 200 films were made in France during the Nazi occupation, most of them routine, a few of them good, but none of them, Bertrand Tavernier observes, anti-Semitic. This despite the fact that anti-Semitism was not unknown in the French films of the 1930s. Tavernier’s “Safe Conduct” tells the story of that curious period in French film history through two central characters, a director and a writer, who made their own accommodations while working under the enemy.

The leading German-controlled production company, Continental, often censored scenes it objected to, but its mission was to foster the illusion of life as usual during the occupation; it would help French morale, according to this theory, if French audiences could see new French films, and such stars as Michel Simon and Danielle Darrieux continued to work.

Tavernier considers the period through the lives of two participants, the assistant director Jean Devaivre (Jacques Gamblin) and the writer Jean Aurenche (Denis Podalydes). The film opens with a flurry of activity at the hotel where Aurenche is expecting a visit from an actress; the proprietor sends champagne to the room, although it is cold and the actress would rather have tea. Aurenche is a compulsive womanizer who does what he can in a passive-aggressive way to avoid working for the Germans while not actually landing in jail. Devaivre works enthusiastically for Continental, as a cover for his activities in the French Resistance.

Other figures, some well-known to lovers of French cinema, wander through: We see Simon so angry at the visit of a Nazi “snoop” that he cannot remember his lines, and Charles Spaak (who wrote “The Grand Illusion” in 1937) thrown into a jail cell but then, when his screenwriting skills are needed, negotiating for better food, wine, cigarettes, in order to keep working while behind bars.

Like Truffaut’s “The Last Metro” (1980), the movie questions the purpose of artistic activity during wartime. But Truffaut’s film was more melodramatic, confined to a single theater company and its strategies and deceptions, while Tavernier is more concerned with the entire period of history.

The facts of the time seem constantly available just beneath the veneer of fiction, and sometimes burst through, as in a remarkable aside about Jacques Dubuis, Devaivre’s brother-in-law; after he was arrested as a Resistance member, the film tells us, Devaivre’s wife never saw her brother again–except once, decades later, as an extra in a French film of the period. We see the moment in a film clip, as the long-dead man collects tickets at a theater. There was debate within the film community about collaborating with the Nazis, and some, like Devaivre, risked contempt for their cooperative attitude, because they could not reveal their secret work for the Resistance. Tavernier shows him involved in a remarkable adventure, one of those wartime stories so unlikely they can only be true. Sent home from the set with a bad cold, he stops by the office and happens upon the key to the office of a German intelligence official who works in the same building. He steals some papers, and soon, to his amazement, finds himself flying to England on a clandestine flight, to give the papers and his explanation to British officials. They fly him back; a train schedule will not get him to Paris in time, and so he rides his bicycle all the way, still coughing and sneezing, to get back to work. Everyone thinks he has spent the weekend in bed.

You would imagine a film like this would be greeted with rapture in France, but no. The leading French film magazine, Cahiers du Cinema, has long scorned the filmmakers of this older generation as makers of mere “quality,” and interprets Tavernier’s work as an attack on the New Wave generation which replaced them. This is astonishingly wrong-headed, since Tavernier (who worked as a publicist for such New Wavers as Godard and Chabrol), is interested in his characters not in terms of the cinema they produced but because of the conditions they survived, and the decisions they made.

Writing in the New Republic, Stanley Kauffmann observes, “Those who now think that these film people should have stopped work in order to impede the German state must also consider whether doctors and plumbers and teachers should also have stopped work for the same reason.” Well, some would say yes. But that could lead to death, a choice it is easier to urge upon others than to make ourselves. What Tavernier does here is celebrate filmmakers who did the best they could under the circumstances. Tavernier knew many of these characters; Aurenche and Pierre Bost, a famous screenwriting team, wrote his first film, “The Clockmaker,” and Aurenche worked on several others. In the film’s closing moments, we hear the Tavernier’s own voice in narration, saying that at the end of his life Aurenche told him he would not have done anything differently.