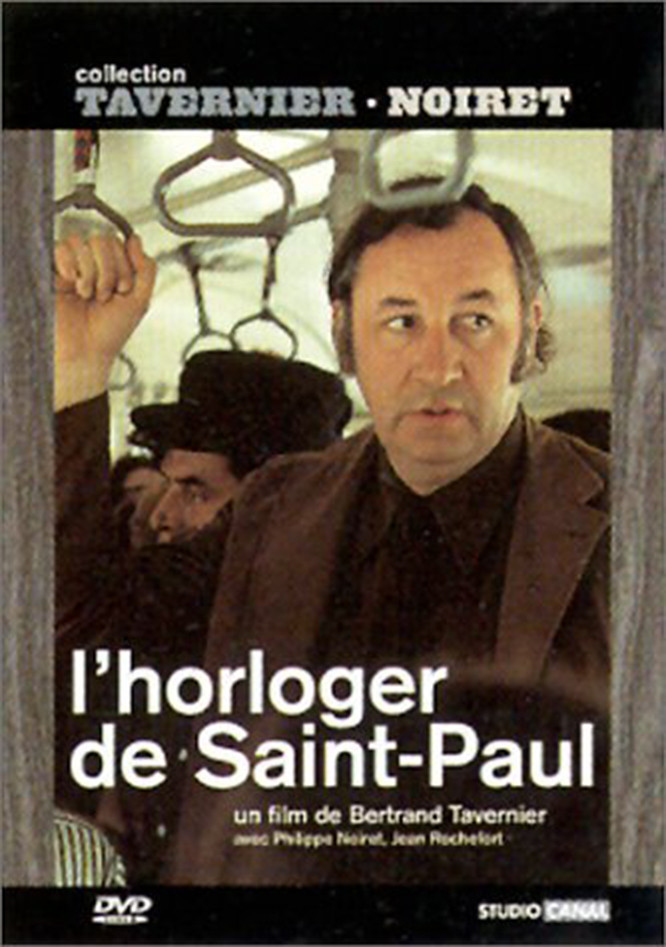

“The Clockmaker,” which is based on a novel by Georges Simenon, begins with the report of a murder and ends as the portrait of a personality. It has that in common with a lot of books by Simenon and other crime writers who understand that people, not crimes, are their real subject (I’m thinking also of Nicholas Freeling and P. D. James). What’s unusual about “The Clockmaker,” though, is its angle of attention: It’s not about the killer, but about the killer’s father. And it presents him so eloquently that it becomes one of the year’s best films. The father is played by Philippe Noiret. You may not recognize the name, but you will recognize the face from a dozen movies: sad-eyed, thoughtful, resigned to middle age. Noiret plays a clockmaker who lives and works in a quiet quarter of Lyons. He is not quite a widower. (“My wife and I separated, and then she died – what does that make me?”) He lives with a son who comes and goes according to his own schedule. One day a police inspector visits the clockmaker’s shop to inform him that his son has committed a murder.

There’s not the slightest doubt, unfortunately: It was the son, and it was murder. Noiret nods gravely. He and the inspector talk about what it is in young people that makes them do these things. Noiret thinks that perhaps he did not pay close enough attention to his son – didn’t display the affection that he felt for him. The inspector listens with sympathy, asks Noiret to report any news of the son and leaves. The clockmaker sits in his son’s room and runs through his thoughts again and again.

We think now that perhaps the movie will be about an investigation; that it will involve elements of a thriller. But “The Clockmaker” is much too good to do that; it transcends the crime genre and becomes a totally original work. And it does that very simply, by revealing characters to us. There will be few surprises and little violence, but the film’s people will absorb our attention and occupy our memories. And by its end, very gracefully, it will turn out to have been about two relationships: one between Noiret and the inspector, the other between Noiret and his son. The clockmaker and the policeman find themselves becoming friendly during the several days of the investigation. In a Simenon novel, there is always a lot of sending out for beer and sandwiches, and “The Clockmaker” is in the tradition. The two men meet for meals, they talk about human nature, they respect each other’s privacy and eventually they become so friendly that they can even be quiet together. Through the father, the Inspector begins to understand some of the son’s motives.

Because the murder, it appears, was politically motivated. Not motivated out of overwrought adolescent radicalism, bur inspired purely and directly by the behavior of the victim, an overbearing shop steward in the factory where the son’s girl friend worked. The son applied a process of reasoning to the situation and arrived at a decision to murder the foreman. Very simple. No regrets.

The son is eventually captured and brought to trial. By now, Noiret has had a long time to think about the case. He discovers, somewhat to his surprise, that in a complex way he is proud of what his son had done – that he can disapprove of murder and yet understand this murder. Noiret says as much during the trial. And, curiously enough, the Inspector in his own way also understands.

The film ends with a quiet, understated reconciliation between father and son. Here, as everywhere else in the film, director Bertrand Tavernier has total faith in his characters. He neither tells us too much nor too little; he looks at them, as Simenon himself so often does, with straightforward acceptance and compassion. “The Clockmaker” is an extraordinary film – the more so because it attempts to show us the very complicated workings of the human personality, and to do it with grace, some humor and a great deal of style.