There were immigrants to America who thought the streets would be paved with gold. Lasse Karlsson, a middle-aged farmhand from Sweden, has more modest hopes as he sails with his young son to Denmark in the early years of this century. In Denmark, he says, they will drink coffee in bed on Sunday mornings, and eat roast pork with raisins for Sunday dinner. He cradles his son, Pelle, in his arms as their little passenger vessel noses into a small harbor, where disappointment sets in almost at once.

Almost everyone on the boat is a Swedish laborer, looking for work. Farmers have turned out to inspect them as if they were cattle.

One by one, the men are hired, until finally only Lasse and Pelle are left. Nobody wants to hire Lasse (Max von Sydow). He is too old. He has a son. Half-drunk and defiant, he all but forces himself on the last of the farmers, a man named Kongstrup who has a shifty look about him.

Lasse and Pelle sit in the farmer’s cart as it passes through fields on its way to their futures.

“Pelle the Conqueror” uses this beginning, full of hope and dreams, in an interesting way. Through the seasons that follow during a long year on the Kongstrup farm, the vision somehow stays alive inside Pelle, even though life seems organized to disappoint him. The film begins with one hopeful immigration – Sweden to Denmark – and ends with another, Pelle’s decision to take his chances in the larger world.

Life on the Kongstrup farm is defined by the land, the seasons, and the personalities of the people who live there. The Kongstrups themselves hardly appear for long stretches of time; they live in a big house set aside from the farm buildings, and Mrs. Kongstrup spends her days drinking brandy while her husband chases wenches. He has no shame, not even about the one unfortunate woman who appears at his front door from time to time, their child in her arms.

In the quarters where the laborers live, life is defined by the sadism of the “Manager” (Erik Paaske), a bully who spots weaknesses in his men and exploits them. He is assisted in his cruelty by the “Trainee,” a youth who takes particular pleasure in tormenting Pelle.

The boy turns to his father for protection, but Lasse is too old and too weary to help. Eventually Pelle makes his own alliances for friendship and protection.

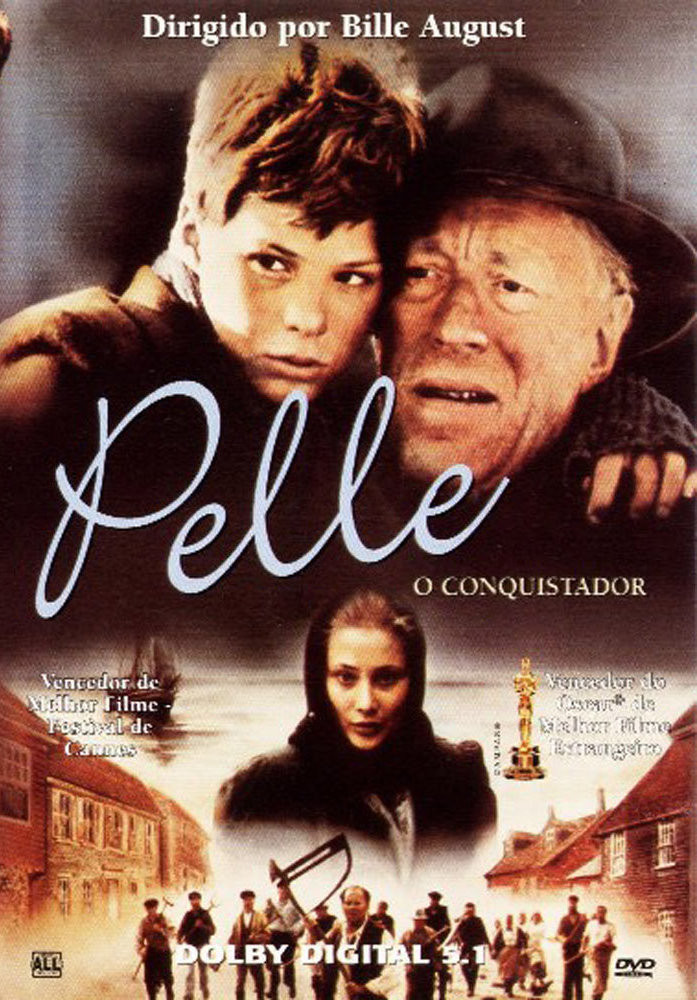

“Pelle the Conqueror,” which won the Grand Prix at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival, was adapted by Bille August, whose previous film, “Twist and Shout,” was about teenagers coming of age in the 1960s. In tone and sometimes in visuals, the movie resembles “The Emigrants” and “The New Land” (1974), Jan Troell’s two-part epic about Scandinavians who settled in Minnesota. Both films star Max von Sydow, that mighty oak of Swedish cinema, who is unsurpassed at the difficult challenge of appearing not to act, of appearing to be simple and true even in scenes of great complexity.

The film is a richness of events. There are scenes of punishingly hard work in the fields, under the eye of the Manager. A challenge between the Manager and an independent-minded worker, with tragic results. The intrigue in the big house, where Mrs. Kongstrup exacts a particularly ironic revenge for her husband’s philandering. The heartbreak of a beautiful local girl, who has fallen in love above her station.

The most touching sequence in the film involves a winter’s romance between Lasse and a sailor’s wife who lives in a cottage near the sea.

Pelle is the first to meet the woman, whose husband has been missing for years and is presumed dead. He introduces his father to her, and the two people take a liking to one another that is practical as well as sentimental. There is a scene of great delicacy and sensible realism, in which they evaluate their resources and decide they should live together, and afterwards Lasse is able to suggest with a smile to his son that they might soon be having coffee in bed on Sundays after all.

Von Sydow’s work in the film has been honored with an Academy Award nomination for best actor, well deserved, particularly after a distinguished career in which he stood at the center of many of Ingmar Bergman’s greatest films (“The Virgin Spring,” “The Seventh Seal”). But there is not a bad performance in the movie, and the newcomer, Pelle Hvenegaard, never steps wrong in the title role (there is poetic justice in the fact that he actually was named after the novel that inspired this movie). It is Pelle, not Lasse, who is really at the center of the movie, which begins when he follows his father’s dream, and ends as he realizes he must follow his own.