While Michael Bay originally conceived “Pain & Gain” as a “small movie” that he would make before his most recent “Transformers” sequel, nothing about Bay’s new film is little. As we’re repeatedly reminded throughout the film, “Pain & Gain” is based on a true story: Between 1994 and 1995, three Floridan body-builders tried to get rich quick by robbing and killing.

In “Pain & Gain,” Bay’s typically vile brand of chauvinism is amplified in order to make a silly but grand cynical statement about the scam that is the American dream. Everyone in “Pain & Gain” is corrupt, decadent, or stupid because anyone involved in an American institution is participating in a giant pyramid scheme, including the Florida Savings and Loan, the Miami PD and the gum-chewing blonde at the local Home Depot.

Bay and screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely (“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe“) don’t hold back any bile here: With one striking exception, all of the film’s characters are immodestly pathetic. “Pain & Gain” is irrepressibly sleazy, frequently exhausting and sometimes as bitterly funny as its creators think it is.

When we’re first introduced to Daniel Lugo (Mark Wahlberg), he’s running from a SWAT team in slow-motion as ropes of spit fly from his gaping mouth. After getting hit by a car, Lugo insists that it’s the responsibility of all Americans to realize their potential. “All my heroes are self-made,” Lugo burbles enthusiastically, adding that anyone who “squanders their gifts” is simply “unpatriotic.” Lugo’s delivering a sales pitch to us, and the product he’s selling is the story of his failed get-rich-quick scheme.

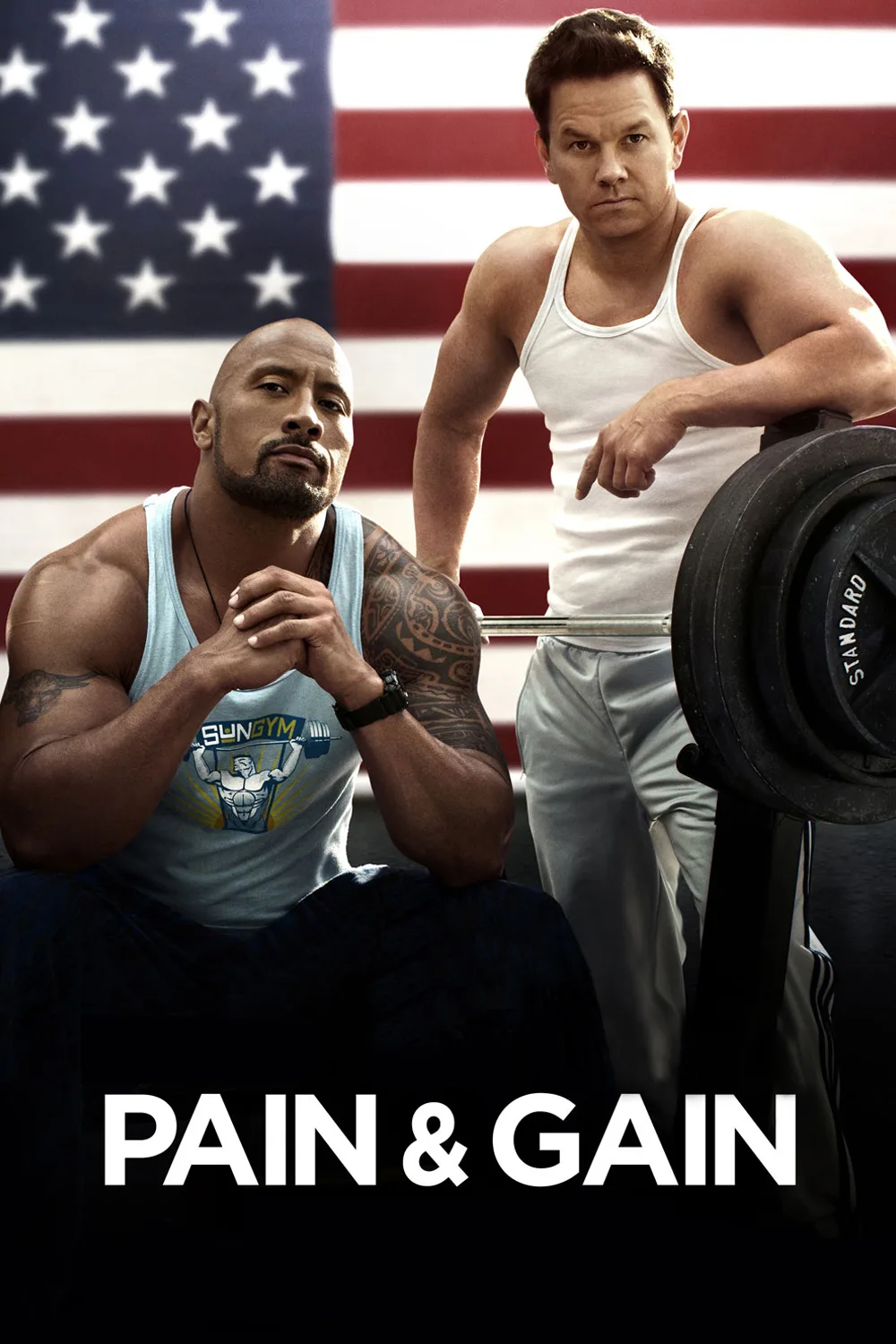

Together with fellow strongmen Adrian Doorbal (Anthony Mackie) and Paul Doyle (Dwayne Johnson), Lugo plots to kidnap and rob slimy entrepreneur Victor Kershsaw (Tony Shalhoub), a client at Lugo’s gym. But Doorbal, an anxious man with steroid-shrunk gonads, and Doyle, a cocaine-addicted born-again Christian, are as simple-minded as Lugo is short-tempered. So while Lugo’s failure is foretold in the film’s opening scene, it’s also treated as the inevitable conclusion to his story because almost everyone in “Pain & Gain” is a narcissistic dimwit.

Throughout “Pain & Gain,” anyone who aspires to authoritatively represent something bigger than himself is dismissed as a dumb shill. Priests are horny, weapons salesmen are Christian rock-listening tools, cops are presumptuous racists, and even Kershaw, the film’s victim, is a loudmouthed opportunist. Kershaw is what Lugo wants to be, an aspiration confirmed when he sneers that salad was invented poor people. That’s a Lugo-worthy line if every there was one.

The teasing promise of more power, status, virility and money makes everyone myopically foolish. Bay rams home that point by juxtaposing the science-fair-worthy neighborhood watch poster boards Lugo makes to dupe his neighbors with the presentation that the Miami police chief gives to his men. In their own crude way, the film’s creators are constantly howling about the pervasiveness of cultural indoctrination. They even go so far as to implicate themselves, if only just to prove they’re not taking themselves seriously, when Lugo tells Doyle, “I watch a lot of movies, Paul. I know what I’m doing.”

The only competent/intelligent character in “Pain & Gain” is retired private detective Ed Du Bois (Ed Harris). Du Bois is unhappy in his retirement and doesn’t like the idea of whiling away his remaining years playing golf or going fishing. He doesn’t pursue Kershaw’s case out of a sense of responsibility, but simply because it’s a way to break up the tedium of his life. But even Du Bois is not infallible; to prove it he’s afflicted with back pain, if only momentarily.

The pervasive juvenile nihilism inherent in “Pain & Gain” is mitigated by its creators’ zeal for destructive social criticism. Bay makes some far-out creative decisions, like his sporadic use of randomly-timed inter-titles such as, “This is still sadly a true story,” or a list of potential side effects of cocaine use, including anxiety and ejaculation.

For his ostensibly small movie, Bay experiments with harness-rig digital camerawork and ostentatious tracking shots that pull viewers through pinhole-sized openings in walls and windows. As ambitious and vibrant as it is ugly and scattershot, “Pain & Gain” is the most charming Michael Bay movie in a long while.