“Mufasa: The Lion King” is a prequel about the origins of the title character, the magnificent and doomed father of the title character in “The Lion King.” It follows him on an epic journey after he’s washed away from his own family down a river and deposited among another pride of lions, then sent on yet another journey with his adoptive brother Taka to locate a promised land described in fables. It walks its own version of a path laid out by other big-budget franchise prequels dating back to George Lucas’s early-aughts “Star Wars” trilogy, alternating wrenching personal drama with fan service touches like showing us how the hero’s chief counsel, the mandrill Rafiki (voiced by John Kani), got his staff, and how Pride Rock was formed.

Those who’ve seen another blockbuster 2024 franchise prequel, “Transformers One,” will figure out quickly where this story has to end up. Those who haven’t seen it will figure it out anyway. There’s even a self-deprecating joke about it in the “Princess Bride”-like framing device, which regularly flashes back to Rafiki telling a story to the cub Kiara (Blue Ivy Carter, daughter of Beyonce Knowles-Carter, who plays Kiara’s mother Nala) while warthog Pumbaa and the meerkat Timon (Seth Rogen and Billy Eichner) create their own riff track that includes jokes about getting in trouble with Disney’s legal department.

The main plot finds Taka (Kelvin Harrison, Jr.) and Mufasa (Aaron Pierre) traveling across Africa to locate a promised land after Taka’s pride is wiped out by a malevolent, insatiably domineering pride of white lions led by Kiros (Mads Mikkelsen). After a certain point, the duo is joined by a female lion, Sarabi (Tiffany Boone), which sets up a love triangle subplot that seems like it’s going to turn into “Jules and Jim” with lions but serves mainly to introduce notes of jealousy and resentment. Kiros is determined to kill Taka to avenge the death of his son during an attack on Taka’s pride but shifts most of his resentment to Mufasa, who is clearly a born leader, capable of inspiring a wide range of fellow creatures, and possessed of an uncanny sense of smell that serves him well throughout his odyssey.

What makes “Mufasa” notable, rather than merely good, is the impassioned and tight direction of Barry Jenkins (“Moonlight”) and the cutting-edge filmmaking systems the movie employs, which I detailed in an article for Vulture. Some of the same animators who would later refine the movie’s visuals performed characters’ physical actions on a motion capture stage in Los Angeles while James Laxton, Jenkins’ regular cinematographer, responded to them intuitively; their movements were translated into a four-legged animal’s movements in real-time and placed within a digital imagining of African terrain (overseen by production designer Mark Friedberg).

Jenkins would seem to be an odd fit for a project like this. He cemented himself as a major American filmmaker with the Oscar-winning “Moonlight,” the James Baldwin adaptation “If Beale Street Could Talk,” and the streaming adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad,” arguably the only dramatic series since David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks: The Return” to advance serialized TV as an art form.

Yet the result is something more lived-in and lifelike than any prior work in this mode. The animal characters feel as if they are performers being photographed while moving through real environments rather than having been designed, drawn, and fleshed out in accordance with storyboards. Laxton’s camerawork, which is uncommonly gentle and expressive for this sort of movie, makes you want to lean in towards the screen, as you might lean in towards a stage during a theatrical production that moves you.

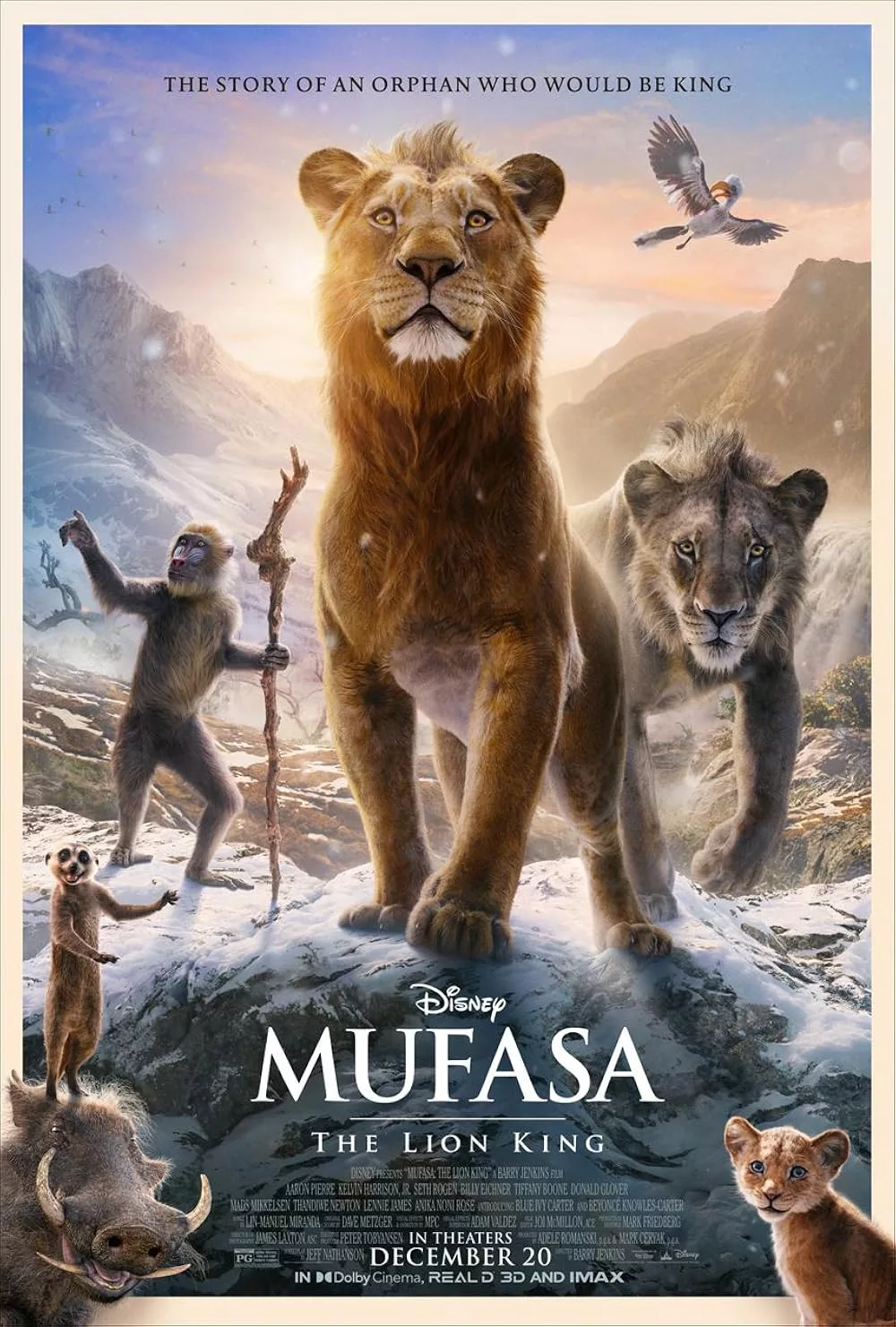

“Mufasa” never offers anything that can eclipse the shock of the new that accompanied the the first photorealistic animated Disney remake in this vein, 2016’s “The Jungle Book.” But the movie is a technological step up from 2019’s “The Lion King,” finding new ways to make the creatures expressive and emotionally available to us while also somehow convincing us that they are indeed animals, whose every talon, whisker, and hair seems as real as imagery in a nature documentary. It’s also the best-directed and most thoughtful entry in Disney’s series of photoreal remakes, which have drawn barbs for replacing the figurative poetry of hand-drawn animation with something more literal-minded. It is visually very much a Barry Jenkins movie, with Jenkinsian signatures appearing in a context that would seem to be hostile to them, from wondrous closeups of characters staring directly at the viewer while framed by a blurred background to the camera moving slowly and gracefully around characters, the rhythm dictated by the characters’ energies.

Jenkins is coloring within the lines here, so to speak. “Mufasa” is a big studio franchise property with catchy songs by Lin-Manuel Miranda. It’s supposed to build out an existing mythology, please entire extended families going to the multiplex over the holidays, and sell merchandise, not subvert or reinvent it. Jeff Nathanson’s script, while sturdy and sensitive, hits all the story beats that a movie like this is expected to hit, whether it’s explaining how the dramatic configurations that we remember from “The Lion King” came to be, or establishing that Taka and Mufasa are brothers in spirit by having them sing a song called “I Always Wanted a Brother.” Also, the idea that there’s a “Circle of Life” with lions at the top of the food chain and that all the other animals are totally OK with that and see the lions as their natural rulers sits oddly with Jenkins’ democratic and egalitarian sensibility.

Nevertheless, the movie really works. Jenkins proves himself an adept director of musical numbers and action sequences, neither of which he was previously known for. After seeing “Mufasa,” it would be easy to imagine him directing a “Mission: Impossible” movie or a full-on, sung-through musical (Miranda’s ”Hamilton” still hasn’t received a proper, fully cinematic adaptation, by the way). Every cut by editor Joi McMillon is crisp and exact; there’s never a wasted frame. Many of the images are breathtaking because of how they’re choreographed and composed, such as the shots of lion cubs swimming or floating underwater (shades of Jenkins’ “Moonlight”), the god’s-eye views of vultures circling animals that are about to fight, and the shades of daylight and nighttime evoked by Jenkins and the army of animators and visual effects artists (the “magic hour” scenes are reminiscent of Terrence Malick).

These aspects and others make the movie vibrate with personality when, in other hands, it might’ve come across as a rote exercise in intellectual property servicing. “Mufasa” never quite bursts free of the constraints placed upon it, but those constraints never stop it from moving, or from being moving. It has a signature, rendered with a steady hand.