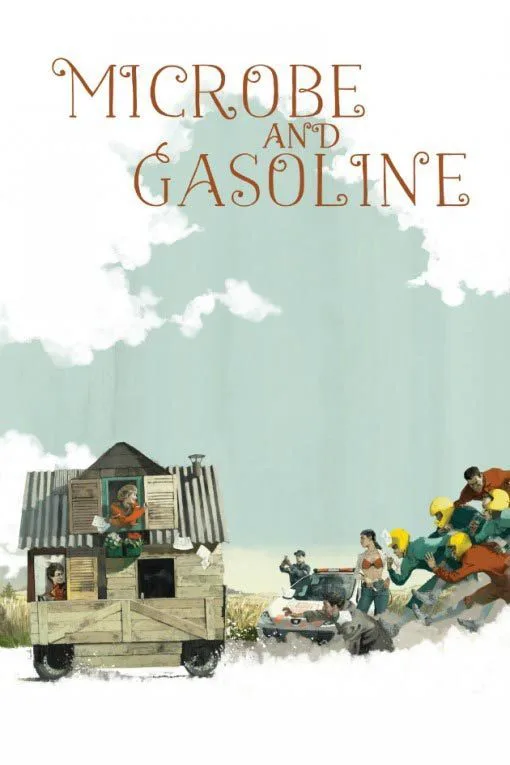

A personal venture that could also be called “Michel Gondry: Origins,” “Microbe and Gasoline” takes place in a cloudy, slow world before creativity blossomed and brought the fast-paced mechanics of the director’s films (“Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” “Be Kind Rewind,” etc.) The setting is Versailles, France—where Gondry grew up—and its DIY narrative spark is primitive: two young men want to get away from their oppressors (bullies, parents, emasculating girls), so they build a makeshift car that looks like a tiny home, as powered by an old lawnmower engine. When school gets out at the end of the year, they skip town and find the adventure they did not expect. Imagination is put into action as Gondry explores themes that have interested him in films as variegated as “The Green Hornet” or “Mood Indigo“: friendship, innocence, creativity, with even more visual restraint than his high schoolers-on-the-bus, slice-of-life-in-2012 drama “The We and the I.” Curiously enough, the result here is more like a creative exercise than a direct look into the soul of an albeit fascinating filmmaker.

The film’s title teenagers are like two halves of Gondry’s brain. Ange Dargent’s Daniel (AKA “Microbe” for his small size) is a budding painter, who creates images of his brother’s punk friends, capturing subcultures with an innocent eye not unlike Gondry’s career as a music video director. Meanwhile, Microbe’s friend Théo (Théophile Baquet) AKA “Gasoline” is the outsider, who has an imagination both mechanical and self-amusing, riding around school on a bicycle suited up with various sound boxes, to produce sounds of a crowd cheering, or a motorcycle engine. He’s the inventive, extroverted side of Gondry—he looks at junk as instruments for creativity, and wants to be an entertainer to his classmates.

Along with their defining hair (Microbe’s long hair that gets him mistaken for a girl, Gasoline’s wild black bush on his head) Dargent and Baquet provide vivid ideas of developing adults finding their place in the world. With a restrained, shy performance, Dargent presents a young man who often battles emasculation, and can only run away from his problems; the larger-than-life Baquet shows Gasoline as someone who wants to transcend his proud eccentricities to be a crowd pleaser, which is especially hard in an environment of conformity. These sensitivities also make the road trip’s dynamics less predictable, as they go from loving to hating each other and back again. Best of all, they express how while Gondry might have innocence as a foundation for many of his characters across films, he isn’t too sentimental to know that kids can be assholes, and the world can bite back—the film takes place from their perspective, so worried parents (including Microbe’s depressed mother, played meekly by Audrey Tautou) are an afterthought, despite some extreme consequences they meet at the end.

Motivation, or lack of it, has always been a strange gear to Gondry’s narratives. His plots are often put into action just because, and like the logic behind his papier-mâché production design and stop-motion animation, the question of “Why?” is often answered with another—“Why not?” For the less-flashy but even more experimental “Microbe and Gasoline,” Gondry only gets so far before he’s dragging viewers with him. The road trip’s strange course of events, which primarily use happenstance, is far less poignant than it is freewheeling. Supporting characters unexpectedly return, irony has a huge part, even Microbe becomes self-aware that he was just in an ellipsis edit. But it all plays out like a cartoon in slow motion; Gondry’s self-amusement here with character and story proves fleeting for everyone else but him. While Gondry calms his creative instincts to toy with the ordinary, he indirectly errs on making “Microbe and Gasoline” his first forgettable film.