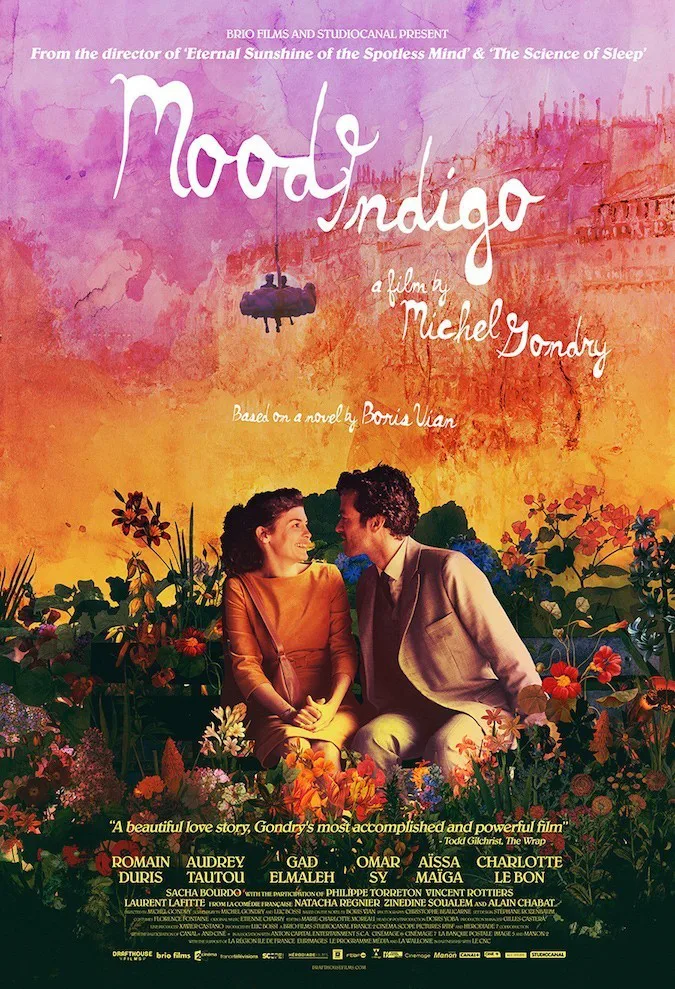

Even if you have a high tolerance for whimsy, “Mood Indigo” may still be too much.

This story of the love between Colin (Romain Duris) and Chloé (Audrey Tautou) is one-stop-shopping for the types of visual and emotional effects that the director’s fans might call Gondryisms. As in “Mind” and “Human Nature” and “The We and the I,” the filmmaker creates surreal or flat-out fantastic images, but with old-fashioned special effects: stop-motion, miniatures that are obviously miniatures, people in animal costumes a step up from what you’d see at a masquerade ball, highly symbolic tableaus built and lit and blocked like stage sets, and so forth. Then he photographs it all in ways that tell your brain, “This is a thing that happened in front of this camera, and we just happened to catch it.” That creates a cognitive dissonance that’s often lovely, and dreamlike in its matter-of-factness.

The problem is that the images are yoked to a story that seems to have been meant as cutting satire—on what, though? Maybe it’s a comment on the disconnect between the upper classes and everybody else, though from what’s onscreen it’s hard to tell. The movie can’t or won’t reconcile the critical aspects of the story (whatever they may be) with the filmmaker’s desire to delight us. The result is a film that seems to be subtly insisting that everything is not fine, even as the director’s tone is saying, “It’s all sunshine and lollipops, folks; love is grand, life is but a dream—and look, here’s another visual miracle!”

The movie is adapted from the 1946 novel “Lecume des Jours” (“The Froth of Days”) by Boris Vian, a source that has been described as a class-consciousness parable about rich people living in a Garden of Eden built from their money and then gradually being forced out of it. Colin and his best friend Chick (Gad Emaleh), Chick’s loyal girlfriend Alise (Aissa Maiga), Colin’s great love Chloé and all of their pals exist in a universe that seems to have the same internal logic as a Max Fleischer cartoon made in about 1938 or so: think Betty Boop or Popeye. People’s legs and torsos flex and twist like bendable action figures or pieces of chewing gum stretched out; these effects are done, it appears, with dummies on strings. This world is studded with marginal surreal touches that are never heralded or explained. Rube Goldberg contraptions are everywhere. Colin has invented a device that produces cocktails based on musical compositions. An announcer at an ice rink is a stiff-looking human-sized bird, like a huge version of what you’d see popping out of a cuckoo clock. The mouse who lives in Colin’s apartment is a guy in a mouse suit scampering across windowsill and baseboard sets. When the mouse needs to make good time he’ll hop in a tiny car and floor it.

Sometimes a scene will shift into stop motion or introduce a random plot development for no apparent reason save the filmmaker’s (or perhaps the original novelist’s) amusement. On occasion “Mood Indigo” will combine one or more of these visual flourishes in a single scene, as when Colin and Chloé’s wedding suddenly turns into a competitive drag race in tiny cars with cross-shaped wheels. The cars move in stop-motion through real environments, the “drivers” frozen in place, their faces frozen in rictus-like grins. The scene climaxes with Colin and Chloé seeming to float out of the church. This is one the damnedest uses of purely mechanical, early 20th century special effects I’ve seen in modern cinema. Apparently Gondry photographed the other guests leaving the wedding, then projected the material on screens in front of and behind his stars, who were suspended in a water tank. They seem to levitate down the steps and onto the street. Air bubbles fizz from the newlyweds’ mouths as they laugh and kiss. Their hair floats. You can see particulate matter floating in the water.

This is all astonishing. The sentence “How the hell did they do that?” appears more than once in my notes. The direction is indeed delightful, as long as you haven’t gotten your fill during the first few minutes, or you’re annoyed seeing social commentary eclipsed by goofy visual pirouettes, or you find Gondry’s casting choices unfortunate, as I did. Many of the actors (but Tatou and Duris especially) are too old to be playing characters who might seem immature even if they’d been played by teenagers. The multicultural ensemble is problematic for different reasons. Kudos to Gondry for envisioning the main players as a racial/ethnic bomber crew, but I wish he’d thought harder about the implications of filling, for instance, the role of the hero’s manservant and chef Nicolas with an actor of color (Omar Sy). Nicolas is an un-ironically eager-to-please, constantly smiling porter-type, ready to Drive Miss Daisy—a construct who’d make modern day audiences cringe were he to appear in, say, a film from the ’40s. At one point Nicolas gets the main couple a room at an inn that we’re told is full by having sex with the proprietor’s teenaged daughter. The leads kid around with Nicolas as if he’s a stereotypical buck who can’t keep it in his pants, and Nicolas protests that he just did what he had to do to get the room. Where’s Mel Brooks when you need him?

The deepest problem, though, is the one I alluded to higher up: This live-action cartoon has elements of scathing satire that are never fully committed to, much less realized. “Mood Indigo” is on some level about what happens to privileged white folks when their cash, identified here as “doublezoons,” runs out, or when a major character is stricken with a debilitating (if storybook) illness, or when any reversal of fortune makes well-to-do leave the Edens they created or were born into. But Gondry doesn’t seem to have the heart of a satirist, even though he has directed satirical or quasi-satirical material in the past. The cosmos seems to be punishing or at least randomly brutalizing his characters, but the director won’t invite us into the heart of their misery and take a hard look at what, in a larger rhetorical sense, it all means. There’s a disconnect between what’s happening to these rich people (repeated smacks across the face, courtesy of our tough-loving pal Reality) and the tone of the movie, which continues to present Colin and Chloé and the gang as lovable, two-dimensional, smiling-and-cavorting man-children and woman-children, and their world as a wonderland that’s a kick to vicariously experience.

The film’s English-language title comes from a piece by Duke Ellington, who was godfather to Vian’s daughter, Carole. The whole story strives for the light, sweet but ultimately melancholy tone of Ellington’s tune, which is used more than once here; but that tone is at odds with the satire, which gets smothered by the moon-sized marshmallow of Gondry’s Gallic cuteness. When a film keeps telling you, over and over, inadvertently or on purpose, “None of this matters,” you start to believe it. If the movie had been ten or 20 minutes long, you might be inclined to forgive its other failures, but it runs nearly 100 minutes (130 in Europe, I’m told). It wants to tickle your fancy and break your heart, but mostly it wears you out.