“You should always have something [to fall back on]. Me, I’ve got magic!” John Candy, doing a slightly pointed sendup of Orson Welles, made that joke in a great SCTV sketch in 1982. The real-life Welles regularly sawed Marlene Dietrich in half to entertain the troops during World War II, and played magicians—or illusionists—in films. His final completed feature, “F For Fake,” opens with him doing a little hand magic, before concocting a remarkable illusion in the form of an essay film for 90 minutes.

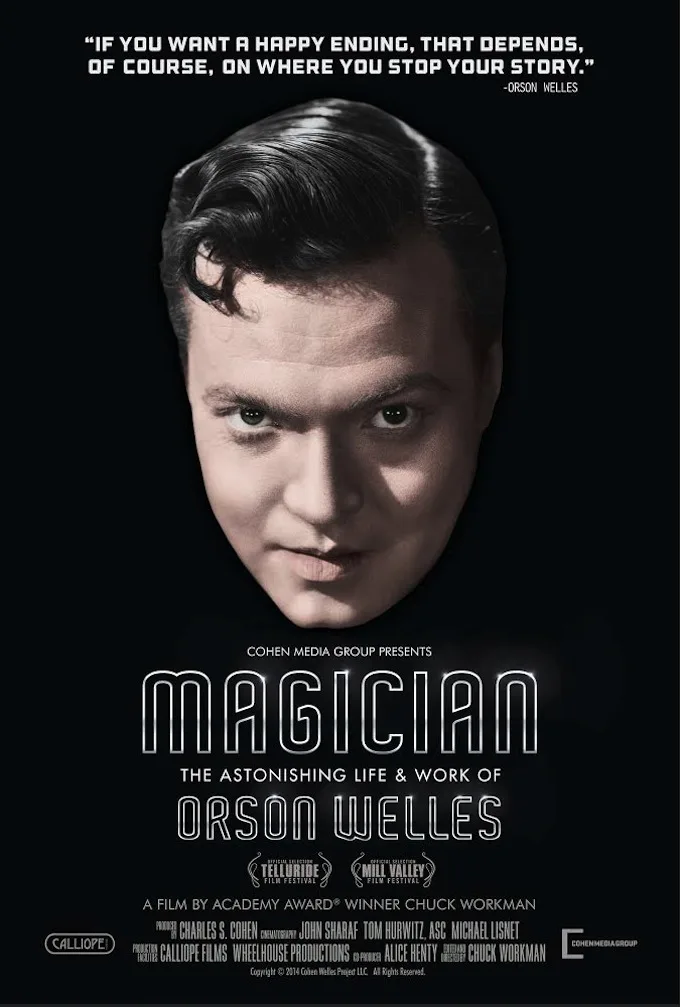

“The magician is an actor,” Welles himself is heard reflecting at the opening of this entertaining documentary directed by Chuck Workman, the master montage-maker whose work is a consistent highlight of the Academy Awards ceremonies every year. “Magician” is hardly a definitive account of the inordinately complex actor and creator that was Welles—at a mere 94 minutes, it could more accurately be deemed the tip of an iceberg—but it offers a not-bad education for folks who aren’t as familiar with the man and his work as they ought to be, and a few not insubstantial satisfactions for folks like myself, who agree with Jean-Luc Godard’s assessment of the man and his work: “All of us will always owe him everything.”

For one thing, Workman’s film tells a different story from that of showbiz conventional wisdom. That is that the always precocious Welles (“there’s nothing more hateful,” he chucklingly admits, than the kind of prodigy he was at the age of ten) was a wunderkind who peaked with his first commercial film (that’s 1941’s “Citizen Kane,” still a ripping yarn, poignant reflection, and galvanic primer of cinema language) and descended into a career purgatory of his own profligate making shortly thereafter. No, throughout its depiction of what it divides up as four phases of Welles’ life, Workman’s movie never stops depicting Welles as an artist: a restless, searching, often frustrated and sometimes frustrating artist, one who never stopped working but who worked in a fashion completely incomprehensible to the conventional wisdom of the cinema industry.

One interviewee points out that film is the only art form in which it’s considered eccentric, if not wasteful, to have left behind as large a body of unfinished work as Welles did. Of course the fact that there is so much unfinished work isn’t quite so bothersome as that it’s so hard to see, and the film seems almost weary in its final quarter as it has to make caveats concerning the unavailability of so much of Welles’ work. Take “Falstaff,” a.k.a. “Chimes At Midnight.” This wonderful 1966 Shakespeare hybrid is confidently proclaimed by actor, director and Welles biographer Simon Callow as “finally, Welles’ masterpiece” (a piece of purposefully provocative quasi-heresy, given the likes of “Kane,” the compromised “The Magnificent Ambersons,” and the magnificent, and largely uncompromised, “The Trial”), but after the few minutes devoted to it the viewer is informed that it’s tied up in legal battles. There’s a sense here that Workman’s film, coming as it does a little prior to the centenary of Welles’ birth, and a possible construction and release of Welles’ last fully shot but largely unedited project “The Other Side of The Wind,” has something of an activist agenda: look at the works of this amazing film and theater director, scattered in disarray over the four corners of the globe, Workman seems to be saying. Can’t we do better?

Film lovers of every generation have to hope we can, and do. In the meantime, while this film elides a lot and makes a questionable choice or two in its portrayals of Welles’ outsize personality (I like Wolfgang Puck’s cooking as much as the next person who’s been to Spago, but I’m not sure his comments on Welles’ epicure side were entirely necessary here), it goes to most of the right people when it comes to shattering the myth of Welles the Hollywood flameout: critic/historians Jonathan Rosenbaum and Joseph McBride chime in with apt observations, and Welles’ longtime companion Oja Kodar is energetic and vibrant and even rather charmingly eccentric. Whatever its shortcomings, “Magician” accomplishes quite a bit as a corrective, and it also gives one an hour and a half in the company of Orson Welles. That in and of itself is worth at least a three-star rating.