You may read other reviews of “Jimmy P.”, a drama about the psychoanalysis of a Great Plains Indian after World War II, that point out how essentially shapeless it is, how it doesn’t really build to anything, and how the drama, such as it is, is talk-driven and rather low-stakes. All of these things are true. But they are minor in the greater scheme. Here is what you really need to know about “Jimmy P.”

First, the movie offers the most psychologically complex screen portrait of a Native American character in at least twenty years, probably more. Second, and related: the titular Indian—Jimmy Picard, a Blackfoot and war veteran who seeks treatment for headaches and catatonia at a facility in Kansas—is played by Benecio del Toro, in one of his greatest performances. Although it would of course have been preferable for the character to have been played by a Native American (del Toro is Puerto Rican), the actor compensates by rejecting the noble savage and “Big Chief” cliches handed down by American films, even comparatively sensitive ones. He creates a character who’s just an ordinary American war veteran who happens to be Native American, and who’s grappling to make sense of his present-tense troubles, his battlefield experience and his childhood pain as any white hero would. Along the way, de Toro does something rarely seen in American dramas made after the golden era of the 1970s: he shows that an ordinary working stiff can be extraordinary intelligent and perceptive, with a streak of poetry—that romantic spirits are all around us, hiding in plain sight.

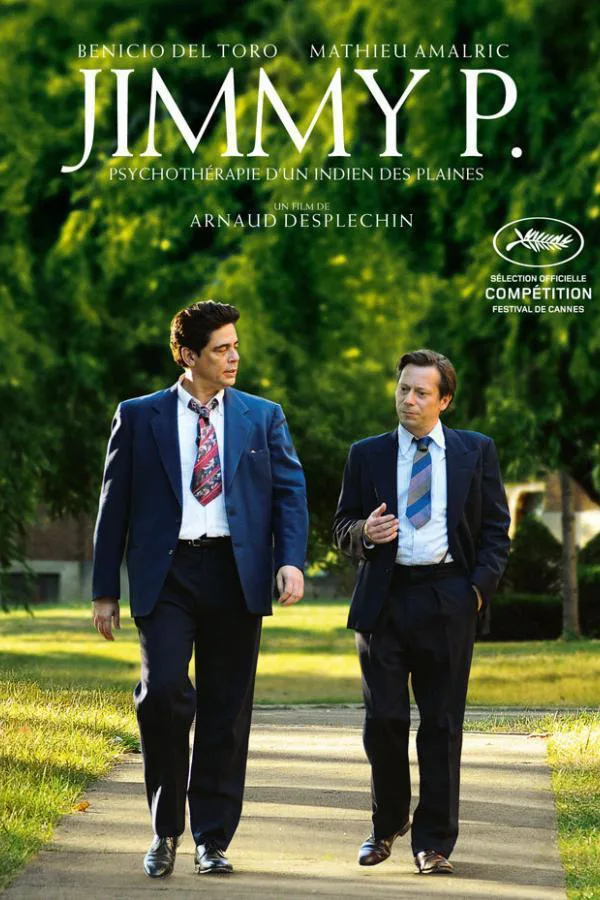

Third, Jimmy and his analyst, a French anthropologist and psychoanalyst named Georges Devereux (Mathieu Amalric), form a great movie friendship, unlike any you’ve seen. Its specialness is rooted equally in the men’s culturally specific yet emotionally similar experiences (they’re both sensitive, wryly funny cultural outsiders) and in the old-school Freudian “talking cure” that they pursue together.

Those who have undergone such treatment will appreciate how accurately the film portrays the process, never simplifying anything, never going for the easy dramatic epiphany, always respecting how analyst and patient circle around and around the edges of meaning. Just as marvelous is the core of true friendship that develops between Georges and Jimmy. They seem to genuinely enjoy one another’s company. They just click, as great friends tend to do in life.

The fourth selling point—and by no means the least—is the filmmaking pedigree. “Jimmy P.” is directed by Arnaud Desplechin (“Kings and Queen,” “A Christmas Tale“). He’s one of the most fascinating mainstream storytellers to emerge in Europe recently. Like David O. Russell (“American Hustle,” “Silver Linings Playbook“), he infuses outwardly conventional genre films with unique moods, rhythms and images.

This movie’s script—co-written by Desplechin, film critic Kent Jones and Julie Peyr (“Four Lovers“)—is actually a fusion of two mainstream genres, the buddy movie and the psychological case study (as represented by everything from “The Snake Pit” through the likes of “Good Will Hunting” and “The Prince of Tides“). They merge so pleasantly, and with such understated respect for the uniqueness of each character that passes before the director’s lens, that you aren’t thinking about “Jimmy P.” as representative of any type of film as you’re experiencing it. You’re just watching a couple of characters get to know each other—and watching people exist generally.

Now and then you may think the movie is headed toward a classic movie-style crystallization that will “explain” Jimmy P. and perhaps instantly cure him of whatever physical and emotional ailments he’s suffering. But this is not the kind of movie that “solves” the hero with “I should have let go” or “It wasn’t your fault”, then sends him off with a hug and a triumphant swell of music. It is instead the sort of film in which the hero might recount a dream involving a bear and a fox, then let you watch as he and Georges spend several minutes unpacking the mythical and personal meanings of those two animals, with the hero actively participating in the process, the analyst learning as much from him as the hero does from his analyst.

Fully half the movie is scenes of Jimmy and Georges talking to each other, joking with each other and digging into memories and dreams. Once in a while you’ll get an interlude which, while charming or lovely, feels less like a continuation or enrichment of the main story than a respite from it. Consider the sequence in which Georges’ married lover (Gina McKee) joins him at the facility. Like a lot of scenes in “Jimmy P.,” I don’t think you could make a case for this one as being urgently necessary, at least not in the Screenwriting 101 sense. But it does give you a chance to see Georges in a different context, and through a different set of eyes, which may in fact be the larger point of the film: that sometimes we can’t truly understand ourselves or our loved ones until we look at them from a different, perhaps somewhat detached, perspective.

All this might not sound like a thrilling evening at the movies to you, and if it doesn’t I don’t begrudge you. I’d just advise you take a whole star off the rating at the top of this review and go see something else. If you’re in the mood for something genuinely different, though—a smart, deliberately meandering film about character, psychology, culture and destiny that never moves as you expect—then you owe it yourself to see this movie, and really watch it, and savor it.