Like “Slingblade,” his celebrated feature debut as writer-director, Billy Bob Thornton’s “Jayne Mansfield’s Car” takes place in the South and has a fine, essentially literary appreciation for the region and its people. But where the earlier film displayed the careful architecture of a well-wrought novel, this new one, with its sprawling array of characters and anecdotal, ramshackle structure, feels more like a collection of interrelated short stories cobbled into an flavorful but ultimately unwieldy narrative.

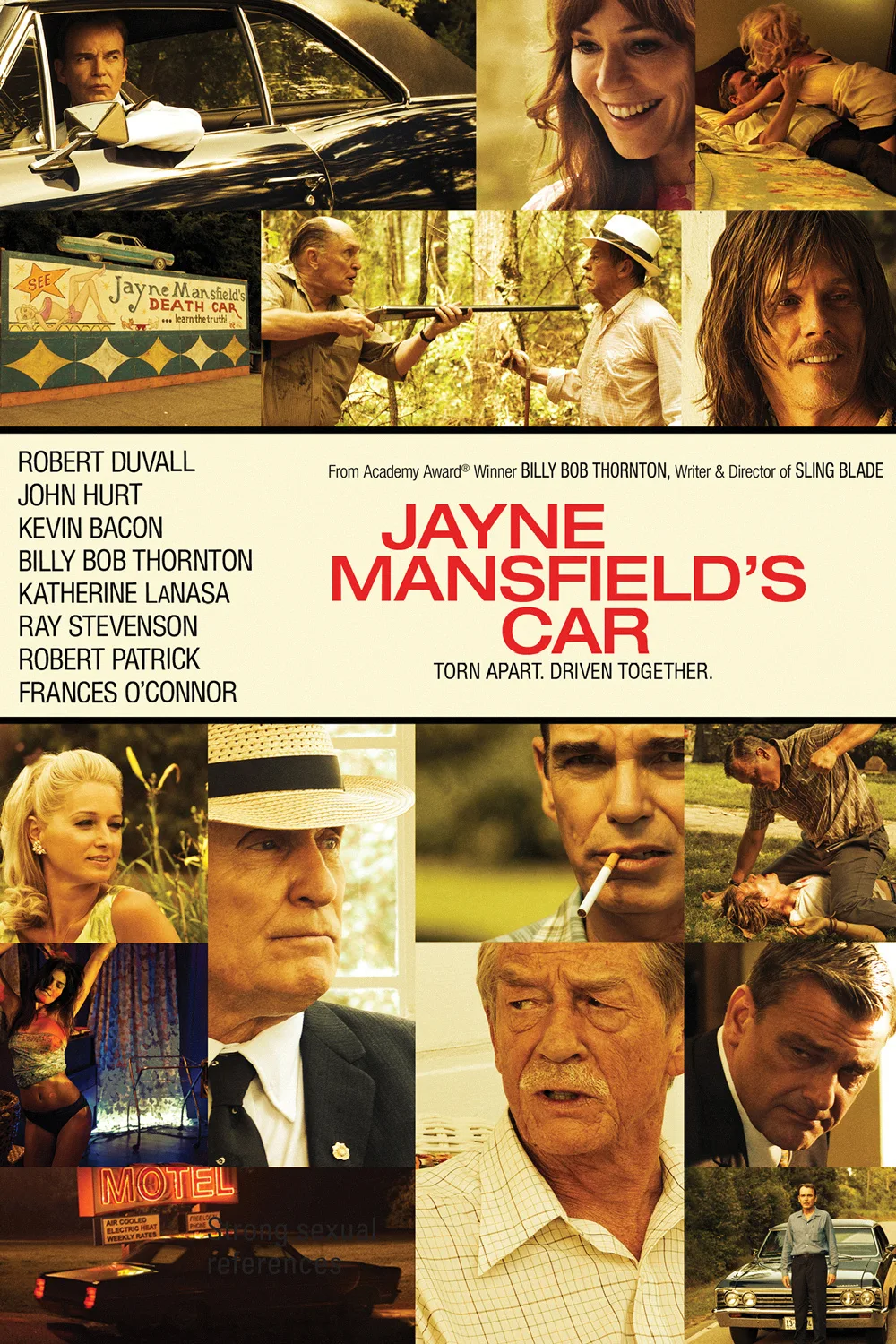

Notwithstanding that problem, the film offers numerous incidental pleasures, including the performances of two grand old lions of the screen, Robert Duvall and John Hurt. And despite its excessive length, the script (by Thornton and Jim Epperson) evidences two main strands: one concerns the effect of war on three generations of men; the other brings a British family into the milieu of a deep-dyed Southern clan for a display of clashing cultures.

The latter strand gives the film the closest thing it has to a plot. The setting: a small Alabama town in 1969. Jim Caldwell (Duvall), a gnarly paterfamilias who’s fascinated by grisly automobile wrecks, has three grown sons of vastly disparate personalities, as well as a daughter, but there’s something missing in the picture of his family life. That element is revealed one evening when a phone call brings news that Jim’s wife his died in England. Seems that decades before she used to beg him to go traveling with her. When he declined, she went off to England, found a new life and never came back. Now, her British family wants to honor her last wishes by bringing her body back for burial.

Thus do the Caldwells meet the Bedfords. Kingsley Bedford (Hurt), the second husband of Jim’s wife, arrives accompanied by his two agreeable but rather colorless grown children, Phillip (Ray Stevenson) and Camilla (Frances O'Connor). “It’s just like ‘Gone With the Wind!'” marvels one of the Brits when they first see the Caldwells’ rural manse. The script’s inter-cultural commentary seldom rises above that level, but mostly it takes backseat to the inter-personal differences. Still wounded by his wife’s abdication, Jim is initially surly toward his unwanted guests, but it’s hard to dislike the gentlemanly Kingsley and his well-mannered kids, so once everyone enjoys a backyard barebque and some frosty beverages, a certain bonhomie develops that eventually allows Jim to discover why his wife left and fashioned a better life with Kingsley.

The story’s other main strand involves different sorts of discoveries and touches on thematic territory that’s potentially much richer. Military service had a strong impact on many Southern families in the last century, but except for a few notable films (such as the memorable Duvall-starrer “The Great Santini“), the subject has seldom been explored in the movies. Here, Jim, like Kingsley, survived the horrors of World War I, and the film gradually lets us see how his character was shaped by the experience. Two of his sons saw action in World War II that affected them in different ways. Skip (Thornton), an eccentric bachelor who dotes on his classic car collection, bears gruesome scars that seem to have given him an understandable aversion to being touched. And Carroll (Kevin Bacon) has become averse to war itself; now a stereotypical late-’60s long-haired, dope-smoking hippie, he leads protests against the Vietnam war that enrage Jim.

The question of war engages all Caldwell males, whether they’ve seen it or not. Skip and Carroll’s brother Jimbo (Robert Patrick), a businessman, missed serving, a fact that may help explain his angry personality. Finally, Jim has two draft-age grandsons (Marshall Allman, John Patrick Amedori) who now face the dilemma of being shipped off to Vietnam or finding a way to beat the draft.

While this thematic element has inherent fascinations, the film doesn’t explore them so much as it scatters them through the narrative as intriguing indicators of character. In effect, Thornton seems less interested in creating a coherent, focused comedy-drama than in fashioning a group of colorful, variegated folks and inviting us to enjoy spending time with them. Indeed, the characters are mostly likable and interesting, and the work of the film’s fine cast adds to our enjoyment. It all comes to an appropriately dark and dizzy climax when Jim gets dosed with LSD by one of his grandsons and finds himself hallucinating dangerously while on a hunt with Kingsley – a scene that reminds us of the still formidable gifts of Duvall and Hurt, whose pairing here may be the one thing that guarantees “Jayne Mansfield’s Car” a place in the history books.

Yet it’s hard to say that this adds up to more than a smattering of ambient amusements. The film’s title refers to the automobile in which movie star Jayne Mansfield was supposedly decapitated in 1967. When a nearby town has a side show displaying the vehicle, Jim takes Kingsley along to gawk at the grisly artifact. Although this Flannery O’Connor-like incident correlates with the comic morbidity that appears throughout the movie, there’s no obvious reason why it deserves bequeathing the film its title. Like too much about Thornton’s film, it seems random.