“Taking the high ground” has both figurative and literal meanings. The former serves as an indication of morality, and describes someone taking what they assume to be a more justified or principled position (“When they go low, we go high”). The latter has a militaristic explanation, and applies to strengthening your position while fighting a foe by elevating yourself above them. One definition makes for better social standing, the other definition for superiority in combat, and both follow a certain hierarchy in terms of whom we consider victors. And both also, argue director Stephen Maxwell Johnson and writer Chris Anastassiades in their film “High Ground,” provide cover for the kind of colonialism, violence, and destruction that invading powers have used for centuries to plunder, subjugate, and oppress at will.

“High Ground” is the latest Australian film—after Jennifer Kent’s “The Nightingale,” Justin Kurzel’s “True History of the Kelly Gang,” and Leah Purcell’s “The Drover’s Wife: The Legend of Molly Johnson”—to interrogate the belief that the continent was just empty and waiting for foreign settlers. When the British arrived in the late 18th century to establish a penal colony populated partially by Irish convicts who were being punished for trying to fight off the British invading their country, and to murder, rape, and enslave the Indigenous Australians already living there, they took control of the widely accepted historical narrative.

You can guess the party line, because something not dissimilar happened in the United States. Indigenous Australians were brutes, savages, and sinners, and only through the monarchy and the Church could they be redeemed. During the Australian frontier wars, whole tribes were slaughtered in hundreds of massacres; children were separated from their parents, renamed, and placed with white families; and none of these things was considered a crime. Hundreds of years later, systemic racism persists, with Indigenous people more often dying in police custody, victims of a “criminal justice system … deeply implicated in the long-term project of controlling and containing colonised peoples,” according to professor Chris Cunneen in a 2019 column for The Guardian.

All of this serves as what historical drama “High Ground,” which Johnson describes as “a story about the finding of one’s roots,” is confronting and interrogating in its tale of two rival factions, one white and one Indigenous, who engage in a 12-year-long conflict. Does Johnson’s director’s statement, in which he refers to the film as the exploration of “the missed opportunity between two cultures, black and white,” hint at both-sides-ism? A bit, and the film’s most obvious missteps involve how its primary characters sometimes feel more like broad types (the hesitant white man, the betrayed Indigenous boy) than like specific people. Also slightly off is the purposeful way “High Ground” seems to equate the violence performed by those defending themselves with that performed by conquerors; there is a subplot involving guerrilla attacks organized by Indigenous survivors that the movie can’t quite decide whether to treat with admiration or admonishment.

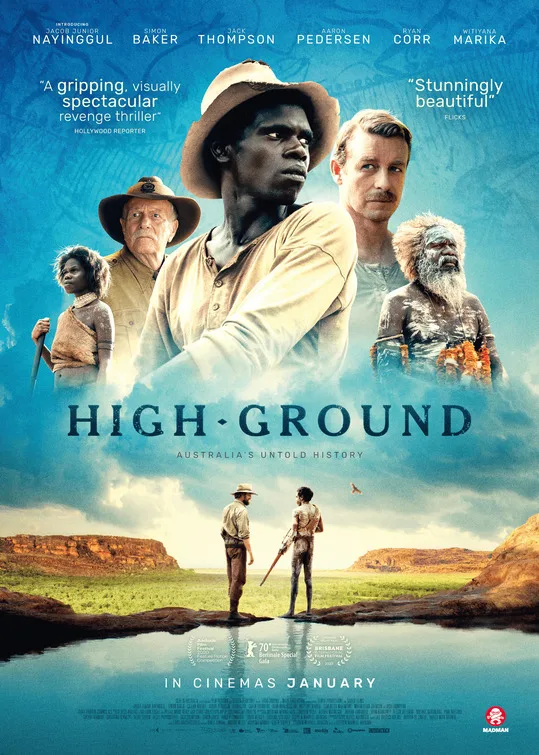

“High Ground” is undoubtedly a difficult watch in that it recreates and centers violence inflicted upon Indigenous Australians to progress its narrative, and a predictable one in that it uses such trauma and white guilt to prove its points. But what “High Ground” does well is provide a showcase for actors of Indigenous descent, who come together into the ensemble cast that is the film’s strongest quality. Johnson and Anastassiades emphasize Indigenous tribal customs, religious beliefs, and familial dynamics in deftly staged scenes: a hunting lesson between uncle and nephew, their bodies smeared with white paint; a communal gathering at the waterside, with relatives of all ages eating and spending time together; a face-off about the country’s laws and future with British officials, whose ignorance is only matched by their pomposity. Actors Jacob Junior Nayinggul, Sean Mununggurr, Witiyana Marika, and Esmerelda Marimowa are all captivating, and their work elevates “High Ground.”

Set in Arnhem Land, Northern Australia, in 1919, “High Ground” begins with a staggering act of cruelty. During what is ostensibly a visit from a Christian missionary to an Indigenous Australian tribe, the accompanying policemen open fire. Watching from his sniper’s position up above, policeman Travis (Simon Baker) is revolted by his men indiscriminately killing the elderly, women, and children, and he saves a young boy, Gutjuk (Guruwuk Mununggurr), from his fellow World War I veteran Eddy (Callan Mulvey). Twelve years later, Gutjuk now goes by Tommy (Nayinggul), and lives at the mission outpost with Claire (Caren Pistorius), the missionary’s sister, who cares for him deeply. A teenager now, Tommy is a dutiful, resourceful young man—but when he learns that his uncle Baywara (Sean Mununggurr), long thought to be dead as a result of that attack, is still alive, something in him shifts. But when the Australian police decide to use Tommy as bait and force him to travel with them into the bush in pursuit of Baywara, Tommy and Travis develop an uneasy camaraderie.

Does Travis still feel shame for what he did, and if so, why is he still following superior officer Moran’s (Jack Thompson) orders to double cross this boy? Does Tommy remember everything that happened to his family that day, and if so, will he sympathize with Baywara, his female comrade Gulwirri (Marimowa), and his grandfather Dharrpa (Marika) enough to leave these white people—even Claire, who has cared for him as she would a son? The Australian countryside is vast, verdant, and treacherous, and cinematographer Andrew Commis captures both the scale and mystery of this place with wide-angle shots of the fields, rock formations, and marshes and more intimate compositions of swarming ants, tree trunk-clinging lizards, and lurking alligators. Nighttime attacks by Baywara’s group on the homes of white settlers are illuminated with fire and juxtaposed with the cacophonous caws of wild birds. A surprise flanking attack by the Indigenous upon Travis’ men is an exercise in foreground and background balance, with bodies emerging out of grass, from behind tree trunks, and out of thin air to draw our attention to various corners of the frame. All of these details help build this world, cementing an atmosphere of harshness and brutality.

Amid all this, the performances of Nayinggul and Mununggurr particularly stick out, with the former communicating Tommy’s increased interest in exploring who he could have been if he had stayed as Gutjuk and the latter capturing Baywara’s laser-focused vengeance. Baker does well too, although his character is so indecisive and spontaneous that it’s difficult to track Travis’ progression over time. Between its evocative ensemble, fluid editing, and interest in Aboriginal culture, “High Ground” is worth a watch, even if it ultimately feels overshadowed by the message it’s trying to send rather than being defined by the story it actually tells.

Now available on demand and on digital platforms.