When the blackly humorous arthouse dramas of Korean filmmaker Sang-soo Hong first arrived in America (from 2002-2004), they were often compared to the work of French New Wave pioneer Eric Rohmer. That’s an understandable point of reference since both Hong and Rohmer are—both rightly and wrongly—often pigeonholed as filmmakers who make conversation-driven, visually spare movies about self-absorbed men who project their own emotions and values onto the elusive objects of their desire, as in Rohmer’s “Claire's Knee” or Hong’s “Like You Know It All.” More recently (2017-present), Hong has continued to develop his own style: non-linear, elliptical, and (often) purposefully repetitive narratives about petty, middle-aged male Korean filmmakers who regret, but cannot stop themselves from alienating their loved ones and love interests, especially shy, independent female artists and/or academics. The typical Hong avatar is mercurial (at best); he lays on the compliments (and poetic observations) a little too thick, always drinks too much, makes everything about him, and inevitably loses control of his own story. He hates himself; he can’t get over himself.

In recent years, Hong’s accelerated his productivity, partly because of a messy and very public affair with leading lady Minhee Kim (long story short: Hong’s wife will not grant him a divorce). Now many American reviewers (understandably) praise the prominence and versatility of actress Kim in Hong’s movies. Unfortunately, many of Hong’s recently imported dramas—even superior efforts, like “Claire's Camera” and “Hotel by the River“—inevitably stop being about unattainable, but free-spirited women and continue being about Hong’s, I mean his stand-ins’, failure to get over themselves. These movies are only superficially about women who get roped into relationships—platonic and otherwise—with Hong-like dudes; most are just about his, I mean his characters’, inability to control themselves. (Hong used to have a reputation for awkward, booze-fueled social interactions at and around film festivals.)

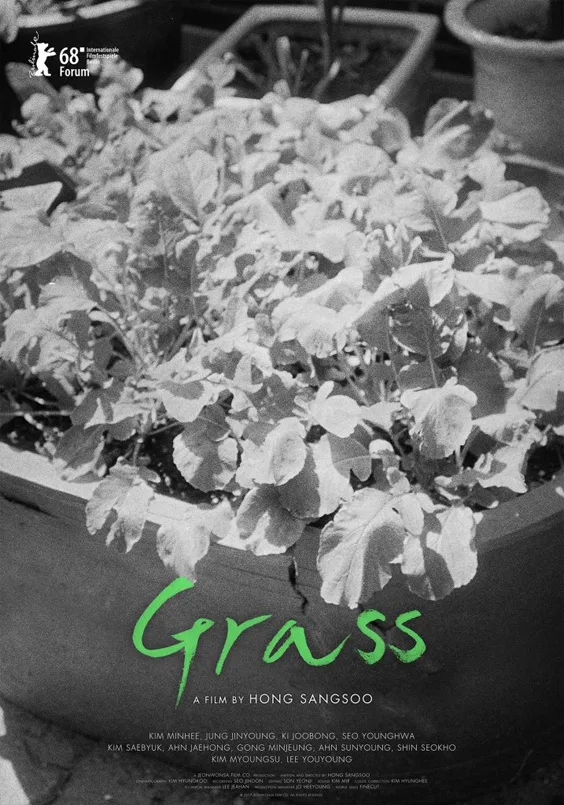

<span class="s1" Thankfully, “Grass“—Hong’s latest movie, and the 14th or 15th by him that I’ve seen—is one of the best expressions/variations on Hong’s usual formula. A black-and-white drama, “Grass” follows a series of characters as they congregate in and around a cafe. They’re not legally allowed to drink there, but they do anyway (the owner says it’s ok). They also accuse each other of being responsible for their loved ones’ suffering and generally act embarrassed when their friends indelicately air out their dirty laundry. Sometimes, it seems like one character is imagining what the others are saying; other times, it’s apparent that they’re just daydreaming in close proximity to each other. One sketch-like subplot begins moments before another ends … only to pick up again later on. These characters’ conversations overlap and inform each other, but never really progress, because these characters don’t really grow before your eyes (or inevitably regress, thank goodness)—they just stew in their emotions.

Once again, Hong’s male protagonists try to feed off of their female counterparts’ creativity; but Hong’s women, led by a characteristically versatile Minhee Kim, can’t submit themselves to that kind of emotional blackmail anymore, and are often forced to say as much. All of these characters worry about each other, even as some accuse others of their own personal failings: You don’t know him like I do. You didn’t love him like I did. Can I stay with you a while? Want to be my writing partner? Sorry, I can’t do that. Please, control yourself. Oh, that’s a shame. Want another drink?

In “Grass” and a couple of other superior efforts—like “The Day He Arrives” and “Right Now, Wrong Then“—Hong suggests a world of meaning through free associations and atonal juxtapositions. Look at the way that he places his camera over the shoulder of sullen actor Jaemyung (Myoungsu Kim) as he, in focus, accuses the recently widowed Soonyoung (Youyung Lee) of driving her husband to suicide. This scene’s dialogue is one-sided: he yells at her while she tries to remain composed. But the scene builds to an unbearable kind of emotional hysteria, until suddenly a raggedy version of “O, Susanna!” (performed on what sounds like a recorder and a triangle) starts playing on the cafe’s PA system. The song doesn’t relieve tension, but rather adds an extra layer of disharmony to the already unnerving conversation. It’s not a tidy scene, but that’s kind of what makes “Grass” so intriguing: we follow characters—many of whom are actors, playwrights, would-be writers—as they struggle to re-write their own narratives. This isn’t just about Hong—it’s about a community that doesn’t know how to continue supporting Hong-like characters.

Hong also articulates a central theme of his work to date: art cannot be used to neatly compartmentalize and/or diagnose one’s own problems. These stories, these conversations … they keep happening because there’s no definite beginning or ending to their implications, not even when some participants die or just leave. So Hong’s protagonists drink, apologize, and struggle to set boundaries with each other. They float from table to table because none of them really belongs to their loved ones’ stories: they just sometimes play supporting roles and then move on to the next bit part.