South Korean director Hong Sang-Soo has made almost 30 features since his directorial career began in the mid-’90s. That’s not Fassbinder-level productivity (which is at least a small part of what killed Fassbinder before he reached the age of 40, so we’re not advocating that) but it’s still impressive. Many of his early features could be described with a line of dialogue from the 1949 classic noir “The Third Man.” You know, the bit where the main character describes himself as “a hack writer who drinks too much and falls in love with girls.” Substitute “screenwriter” or “director” for “hack writer” and you’re pretty much good to go.

Hong has managed to mine this vein productively while gradually introducing intriguing variations. 2017’s “Claire’s Camera,” for instance, had an aging probable-alcoholic filmmaker as one of its characters, but centered the narrative around two women in his life and the title character, a French woman played by Isabelle Huppert whose instant camera seems to have time-bending qualities.

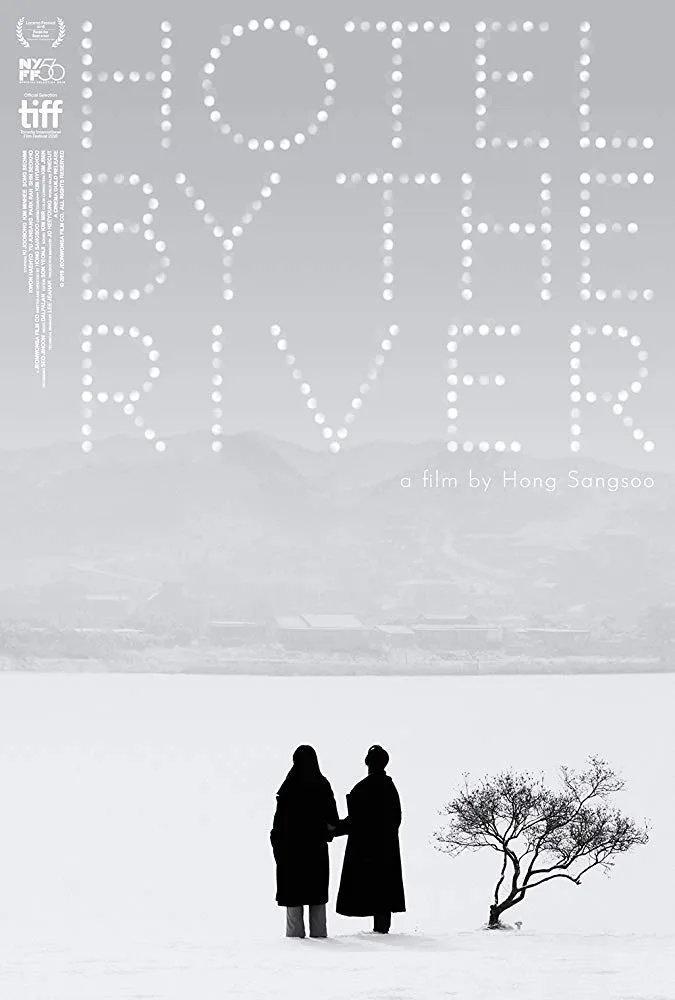

“Hotel By The River” sees Hong following a different formal tack than the one that shaped the nearly fantasist, cleverly self-reflexive “Camera.” This is his third film in a row to be shot in black-and-white. And it’s set in winter, which accentuates a certain somber quality.

One of the temporary residents of the title hotel is a renowned poet, Ko Younghwan (Ki Joobong), who’s decamped there to set up a meeting with his two estranged sons. He looks out his window in the morning and sees a young woman standing in the snow; she’s Sanghee (Hong regular Kim Minhee), recovering from a breakup that has something to do with the wound on her hand that Youngwhan notices right off the bat. These two characters are heard in interior monologues as well as dialogue, although there’s no real narrative rationale for Hong to accord them this privilege.

But such is the nature of this movie. It’s like a series of charcoal sketches with marginalia; there are unexpected mini-flashbacks, and even a visualization of a poem. Hong’s free style isn’t showy; there’s a stillness holding the film together at all times.

Which may prove a challenge for film lovers who welcome more narrative momentum. Hong has enough of a western fan base that he doesn’t necessarily need to appeal to many outside of it. For those viewers, the picture has a better than decent quota of rewards. The characterizations are both unsparing and affectionate. One wants to look through one’s fingers when Youngwhan approaches Sanghee and her visiting friend and announces that he’s “a real poet, with a book and everything.”

Once Younghwan is met by his two adult sons, Kyungsoo (Kwon Haehyo) and Byungsoo (Yu Junsang), and he announces that while he has no discernible illness, he believes that he is dying, understated emotional fireworks begin to ignite. Schlubby Kyungsoo looks almost as old as his father, and ladles a lot of “dad always liked you best” resentment on Byungsoo, who’s now a reasonably successful filmmaker. (“What films does he make?” Sanghee asks of a visiting friend. “You wouldn’t know them, they’re not your type” the friend replies.) The older son seems to take particular pleasure in telling Youngwhan that his ex-wife, the boys’ mom, considers Youngwhan “a total monster without a single redeeming human virtue.”

The exchanges don’t resolve anything, but the story does conclude on a definitive note, one that, like most of Hong’s films, is both sad and strange in equal measure.