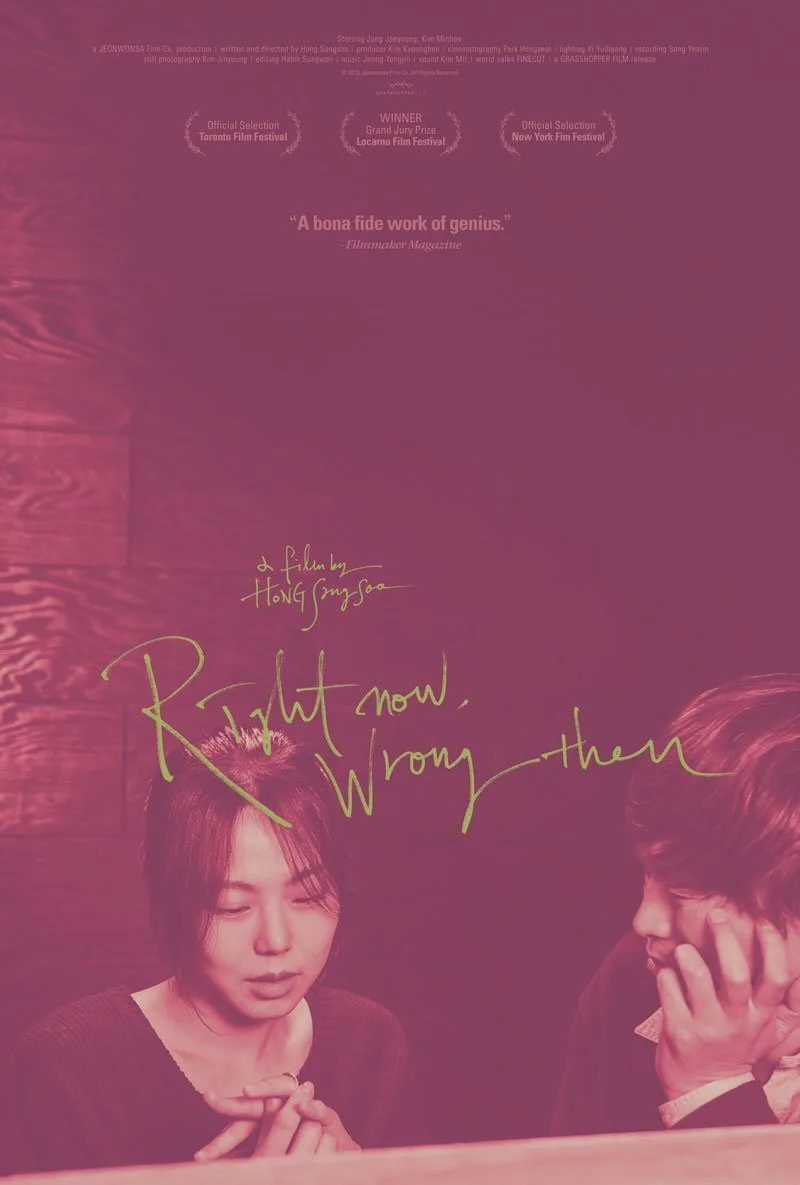

Somehow, until now, I have never experienced a film by South Korea’s Hong Sang-soo, who made his debut as a director back in 1996. From what I gather, though, his low-budget efforts tend to contain similar elements: A self-impressed film director, a movie critic, an attractive girl, awkward social interactions and drinking binges. Sounds as if his oeuvre should be dubbed “mumble-Korean.”

Judging from “Right Now, Wrong Then,” Hong’s approach also is heavy on conversations conducted during long languid takes while bereft of any pulse-pounding cataclysmic events. A visit to an outdoor ice rink that provides miniature sleds instead of skates to glide upon is as close to an action sequence as the movie gets.

But with his 17th feature, he has discovered a rather clever way to repeat himself anew. He splits “Right Now, Wrong Then” down the middle, presenting the same characters, locales and circumstances twice during an identical 24-hour period yet with adjustments both obvious and subtle. Imagine “Groundhog Day,” if Bill Murray only had two shots to get it right. Or Woody Allen’s “Melinda and Melinda,” but without any toggling between comedy and tragedy. Or “Before Sunrise” with two sunrises.

The basics are the same: Because of a scheduling flub, noted Seoul-based art-house director Han Chun-su (played by Jung Jae-young, a lanky sort who sports a sweeping curtain of dark bangs) arrives a day early to a wintertime film festival in Suwon, where he is scheduled to screen one of his works and participate in a lecture. We quickly surmise that he has an eye for his attractive female fan base, including a festival worker, who gushes “you are the most important director to me” as he basks in her flattery.

While touring an ornate, ancient palace, he happens upon Hee-jung (Kim Min-hee), an introverted painter and former model who recognizes his name but has never seen his films. They end up spending the day together, drinking tea and coffee, visiting her art studio, going out for sushi and indulging in numerous shots of rice alcohol before stumbling together to her poet friend’s small party at a cafe.

Some shifts are cinematic, such as the outdoor lighting, camera angles, perspectives and outcomes that lead to a variance in tone. As a result, the first hour—which playfully opens with the heading “Right Then, Wrong Now”—feels colder, draggier, more aloof and downbeat. The second is warmer, funnier and candid—and, because of those qualities, ends on a sweeter, “Lost in Translation”-type melancholy note.

But our perception of what happens is most dramatically changed by the intriguing ways that the two leads skillfully transform their performances. In Part 1, Han is clearly on the make as he disingenuously engages in mundane chitchat with Hee-jung. At her studio, he puts a positive spin on her efforts at abstract painting by noting that she basically goes with the flow without a plan and how that is a “hard path”—which, we learn later, is the way he regularly describes his own relationship to his films. After imbibing too much soju, Han comes on strong as he repeatedly tells Hee-jung that she is pretty and, as will be eventually revealed, is hiding an important fact from her.

As for Hee-jung, she portrays herself as a loner, one who is insecure, adrift and somewhat sheltered—especially when we find out she lives with her mother, who is impatiently waiting up for her when she gets home. But in Part 2, Han and Hee-jung are much more on equal footing. It is clear that he is interested in her not just as a potential conquest but as a person as he masterfully draws her out of her shell. The same filmmaker who comes off like a pretentious creep during the first portion, even angrily berating his interviewer at an ill-attended Q&A, is now honest, open and caring about others—which allows Jung multiple occasions to deploy his sigh-inducing smile. Unfortunately, he becomes a bit too candid when he criticizes Hee-jung for not taking enough risks with her art. He apologizes for his remarks—when asked if all directors are like that, he answers with a knowing grin, “Yes, we are”—but they seem to have a positive effect as well.

Hee-jung, on the other hand, feels less directionless and more in control. Perhaps it is the fact that she is attempting to stop smoking and drinking to excess shows that she is striving to improve her life. And, instead of putting up her guard, she ever so gently opens her heart even if it is clear that this couple is not meant to be.

So what are we to make of all this opportunity to compare and contrast? Does it mean something that the orange paint that Hee-jung uses in the first half later is substituted with green? Or that Han elects to use the hood on his jacket to ward off the cold in the second portion when he first encounters her? And how do the small choices we make on a daily basis affect how we relate to others and the outside world?

Despite the fact that not much of actual consequence happens during “Right Now, Wrong Then,” Hong does much more right here than he does wrong. On its own, each hour doesn’t have much impact narratively. If all I saw was the first half, I would have given it a shrug and left in a semi-foul mood. But the whole is greater for being two parts in this case, making me glad that I have finally lost my Hong Sang-soo virginity.