Cinema is replete with examples of stories about old couples getting their groove back in their later years. Old age is, after all, a kind of new adolescence, as kids grow old, careers become less important, and your dwindling remaining years gives you more license to throw caution to the wind. That is, if you’ve got enough social and financial capital to pull it off — which is why a lot of these kinds of films (from “Book Club” to “Something’s Gotta Give”) tend to feature upper-middle-class seniors luxuriating in the exotic destinations and well-furnished homes that give them license to find love, rather than stress about their shrinking 401(k)s. “Golden Years” is one of these films, as cloying and unassuming as one could expect. But luckily, it’s got a lot more on its mind, and its solutions to the problem of a dead-bedroom marriage are novel enough to offer something more substantial.

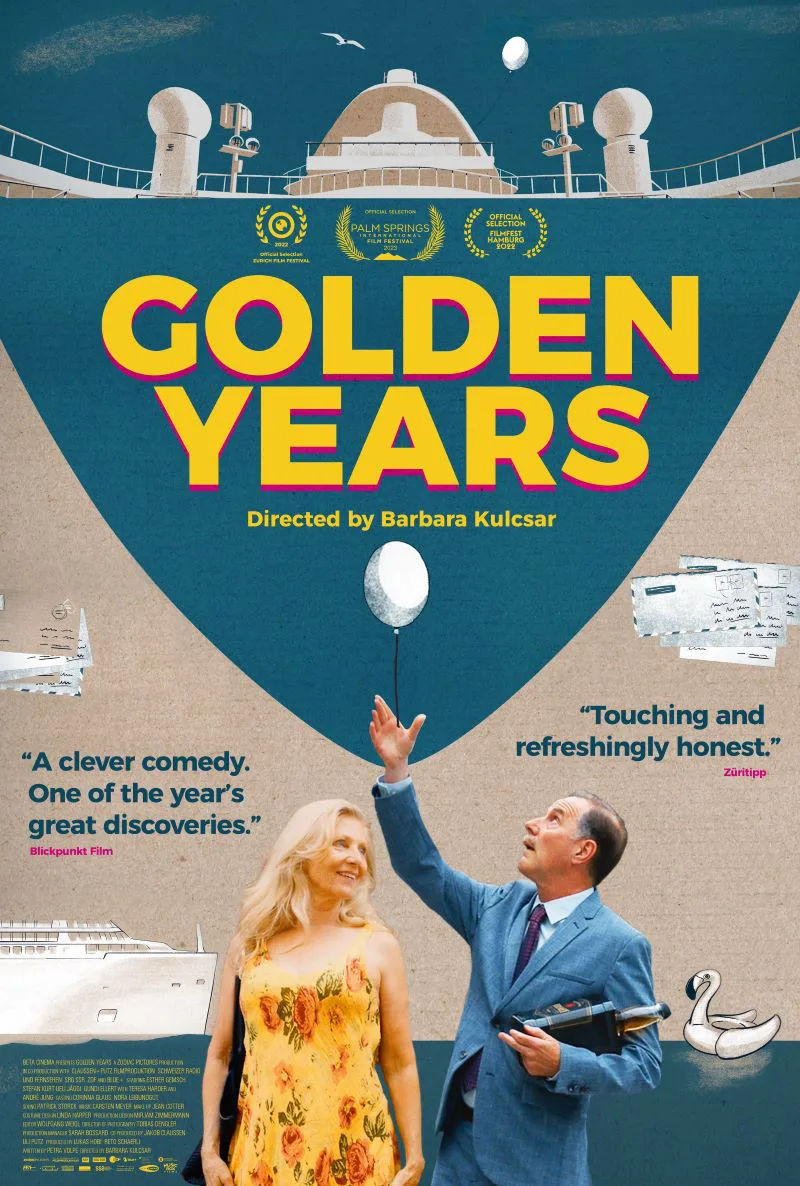

Barbara Kulcsar’s film begins at a moment of transition: Sexagenarians Peter (Stefan Kurt) and Alice (Esther Gemsch) prep for retirement after the former packs up his desk following 37 years of loyal service. (No one will be filling his position; his office will become a server room. Even his job is redundant.) Both look forward to the freedom that retirement will bring, but that means something different to each of them: Alice wants to use this time to rekindle their passion, but Peter has grown used to his habits of obsessive cardio and just wants to be left alone.

But two incidents thrust the pair into a radical reassessment of their lives and love for each other. First, Alice’s close friend Magalie (Elvira Plüss) dies unexpectedly on a hike, but not before pointing Alice towards love letters she’s kept from a mysterious lover she’s had an affair with for fifteen years. Then, Peter and Alice’s kids give them two tickets to a Mediterranean cruise as a gift. Alice is thrilled; this is the chance she’s been waiting for to rekindle their fire. But Peter is less than enthused, which may be one reason he’s invited Magalie’s widow, the kind but morose Heinz (Ueli Jäggi), along with them in his time of need.

At this point, it’d be tempting for “Golden Years” to go down a more gruesome, tongue-in-cheek class satire aboard a cruise ship, a la “Triangle of Sadness.” But Kulcsar and screenwriter Petra Volpe are interested in something far gentler and loping, which makes for paradoxically more fulfilling viewing. It doesn’t take too many days of Heinz eating up Peter’s time and attention, and the latter’s resigned admission to Alice that he’s no longer interested in sex, before Alice literally jumps ship in Marseilles. She wants a “time out” from her dissatisfying marriage, and wanders Europe to return Magalie’s letters to her long-lost lover.

Simmering at the heart of “Golden Years” is the way that traditional notions of matrimony and life can suck the soul out of living — how decades of compromise can leave two people stuck together despite having nothing else in common. Blessedly, while Alice is the one more actively getting her groove back (complete with encounters from other older Europeans with more, let’s say, elevated perspectives on sexuality and fidelity), Kulcsar doesn’t forget about Peter’s more modest aspirations, as he and the quiet Heinz find their own cozy, domestic equilibrium together. Both want to spend their last days in their own ways — Peter by running away from death, Alice by running towards life — neither of which is compatible with the other.

“Golden Years” moves through these forked journeys at an extremely casual pace, which can make the whole thing feel more than a little insubstantial. After all, at the end of the day Peter and Alice will be materially fine, and the sunny cinematography and Carsten Meyer’s cloying, Casio-heavy score do little to make Alice’s late-in-life sexual rumspringa feel all that vital. At the end of the day, these characters simply don’t have any real problems, and it can be aggravating to see folks hem and haw about their futures amid their elegantly furnished Swiss homes. (Even Alice’s bohemian son, who takes her in after an angry Peter kicks her out for leaving him on the cruise, hosts his nightly Tinder hookups in a decidedly cozy bungalow.)

But what wins out are the performances, which pack plenty of pathos within such charming, frail packages. Gemsch, in particular, is soulful and gorgeous as Alice, a church mouse who throws herself into the hedonism she spent her life avoiding like a duck to water. The way she peels back Alice’s layers of repression inch by inch, from the uptight housewife in Act 1 to the relaxed, liberated person she becomes in the closing minutes, is the film’s primary magic trick.

“There are other options than marriage or solitude,” a character tells Alice late in the film. This is where “Golden Years” finds its most invigorating footing, especially as it zigs where most late-life romantic dramedies zag. Instead of treating bisexual flings or trips to a “socio-feminist collective” as temporary detours on a road that leads back to monogamy, Volpe’s script dares to ask its characters whether they owe it to themselves to let go of old ways of thinking and find something that works for them. It’s frothy and insubstantial, but at least takes its central idea — life’s too short, start a polycule — seriously enough to be charming.