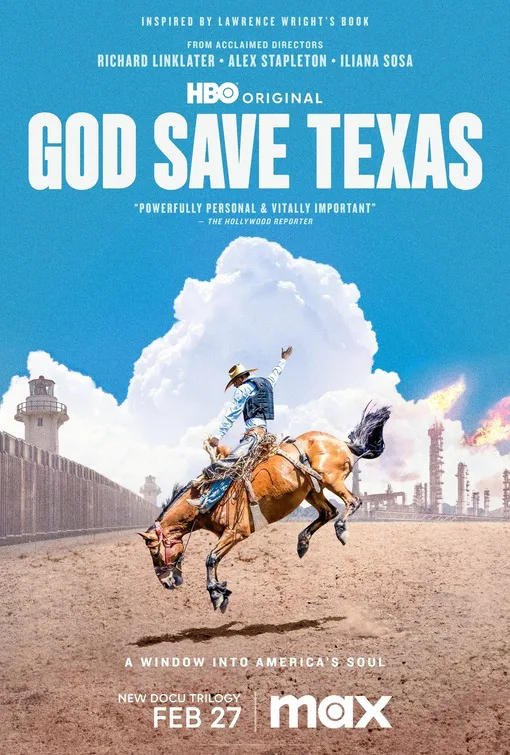

There’s a wonderful scene in Texas filmmaker Richard Linklater’s sprightly comic docudrama “Bernie,” about a murder in the town of Carthage, Texas, where a man in a diner explains that Texas is actually five states, then pithily summarizes each one. A version of that sensibility animates series “God Save Texas,” now on Max. Inspired by the same named book by Texas writer Lawrence Wright, and featuring Wright as a sort of mascot and sounding board throughout, the series offers three episodes, each directed by a different Texas filmmaker (Linklater, Alex Stapleton, and Iliana Sosa), each concentrating on a distinct region of a state that has 29 million people and is big enough to cover France. It’s fascinating to see Texas portrayed through sets of eyes that share a baseline political sensibility (all three directors are liberals in an institutionally right-wing state) but that differ in terms of their cultural background (Linklater is white, Stapleton is Black, and Sosa is Mexican American and has family on both sides of the border).

Ultimately, however, “God Save Texas” is a work of protest and lament. It regularly circles back to the idea that all is not well in America or Texas, despite what our self-serving mythology keeps telling us—and that prejudice is at the heart of most of the trouble, and always has been. The three episodes don’t break any fresh ground in terms of style or structure and aren’t really trying to. They’re put together like road-trip documentaries, and position each filmmaker as a combination host, reporter, local culture expert, and memoirist. The material might be depressing beyond endurance if it weren’t leavened with a distinctively Texan brand of droll humor, as well as autobiographical detours and self-contained bits that feel almost like Wikipedia rabbit-hole dives.

In addition to all that, Linklater’s opening episode doubles as a guided tour of the Texas part of his filmography. His hometown is Huntsville, Texas, where the local economy is based on incarceration, and where over 1000 people have been executed in the city’s eponymous penitentiary. (They do lethal injection now; they used to have a workhorse electric chair, nicknamed Old Sparky.) Driving around town with Wright, Linklater keeps encountering places that inspired his Texas movies, including a rooming house that he shared with some football teammates (“Everybody Wants Some!!”) and the part of town where teens used to hang out, make out, and drive in circles (“Dazed and Confused“).

But there’s a sorrowful undertone to the trips down memory lane, because the coming-of-age happened in the shadow of one of the more relentless carceral engines in the nation, with wave after generational wave of mostly poor and minority inmates being dehumanized, rented out for barely-paid or slave labor, and brutalized or killed by guards. One of the most subdued yet affecting parts of the episode shows the ritual of released inmates leaving prison with barely any preparation for the brick wall of indifference and exploitation they’re about to slam into. Punishment is supposed to be coupled with rehabilitation. But post-1980s, the US gave up on the second thing, and now seems to sadistically enjoy the first, even dreaming up ways to make the penal experience crueler for inmates’ family members.

Stapleton’s episode moves to the Gulf Coast area, the nucleus of the state’s petroleum industry. We find out about Texas’s longtime commitment to slavery, which not only sparked its decision to break away from Mexico in the 1840s (it used to be a territory) but seems to have carried forward as a mentality, into the Jim Crow and Civil Rights eras and beyond. Like the other episodes, this one is loose and discursive and gives itself the freedom to take thematically relevant detours. We learn about the racial redlining that denied Black war veterans the chance to own homes under the G.I. Bill, legislation that mainly benefited white families; anti-Black discrimination in real estate development, banking, petroleum, and trucking; white Texas city bosses’ long-standing preference for dumping garbage and toxic chemicals in Black neighborhoods; and the so-called “sundown towns” that warned people of color to get out by nightfall or be lynched by morning.

Thanks to the restrained, unsentimental way that Stapleton’s subjects speak for themselves (displaying a variety of regional accents in the process) there is a never a “woe is me” sense to any part of the larger story. The director has the instincts of a committed regional novelist. In the Linklater tradition, she lets her subjects speak long enough to establish themselves as characters. We get a sense of what their voices sound like, how they tell stories. Some anecdotes are so understated in their delivery that they transform into an existentially bleak kind of comedy, as when Dennis, the filmmaker’s cowboy cousin, talks of driving through Jim Crow-era sundown towns that have maintained their animosity: “You can just tell that a person like me shouldn’t be there, just by some of the stuff they have written on the gas stations out there. You’d see on a sign, ‘Don’t let the dark catch you out here.’ I kinda know where they’re aiming at with that.”

Sosa’s episode focuses her roots in the border area between Ciudad de Juarez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas, often referred to as La Frontera. “Two sister cities with one heart” is how they were described to Sosa as a girl, but it won’t startle you to learn that this, too, turned out to be something between a mirage and a cover story. Sosa and many of her subjects touch on the idea of a bifurcated consciousness, living simultaneously on two sides of a divide that’s political and cultural as well as geographical. (If anybody ever wanted to remake “Wings of Desire,” they could set it here.)

Just as Stapleton’s episode was rich in mostly untold stories about institutionalized discrimination against Black people who helped build and maintain the Lone Star state, Sosa’s delves into the border region’s role as a gateway for immigrants who have cycled between being courted or lured here when their labor is desperately needed (as it was during World War II) and treated as vermin by xenophobic politicians at the same time that they were being employed off-the-books for sub-minimum wages. One of the most heartbreaking sections is about attempts to bulldoze a working class Mexican-American neighborhood of El Paso in order to build yet another sports stadium. (Northern white folks shouldn’t get too smug watching this part of the episode: nearly all of the freeway interchanges and stadium complexes built in Yankee as well as Southern cities originated in eminent domain seizures of minority-owned land.)

This material connects with stories of political and territorial mistreatment of Black people in Stapleton’s segment, in particular a section where Dr. Robert Bullard, the Texas Southern University professor who’s known as the “Father of Environmental Justice,” reveals that between 1920 and 1978, four-fifths of all the garbage produced in Houston was dumped in Black neighborhoods. It’s all part of the same ongoing story. The through-line is the tail of white supremacy wagging the dog of governance.

All three episodes express a guarded optimism about the possibility of lasting progress, even as they warn that their state is entrenched in reactionary regression and it takes a stubborn, combative sort of progressive to decide to stay and keep fighting rather than move somewhere hospitable. A white liberal activist in Linklater’s episode says that he tried relocating to a “granola” part of Colorado but came back to Texas because he realized that his personality required more people to argue with and try to convert. That’s kind of the same predicament faced by this series. “God Save Texas” fits snugly into the progressive, multicultural, “urban” grid of HBO-Cinemax. But in an ideal alternate universe, it would have premiered somewhere like Country Music Television or Fox News Channel, where its impact would have resonated like the cannons of the Alamo.