In June 1963, Medgar Evers, a Mississippi NAACP leader, was shotdead while standing in his driveway. A man named Byron De La Beckwith wascharged with the crime, but went free after two all-white juries reacheddeadlocks.

AlthoughDe La Beckwith was clearly the killer, at that time and place he was impossibleto convict; there is an obvious parallel with the O.J. Simpson verdict. Sopoisoned was the atmosphere in the Mississippi courtroom that at one point thestate’s governor, Ross Barnett, actually walked up to De La Beckwith and shookhis hand.

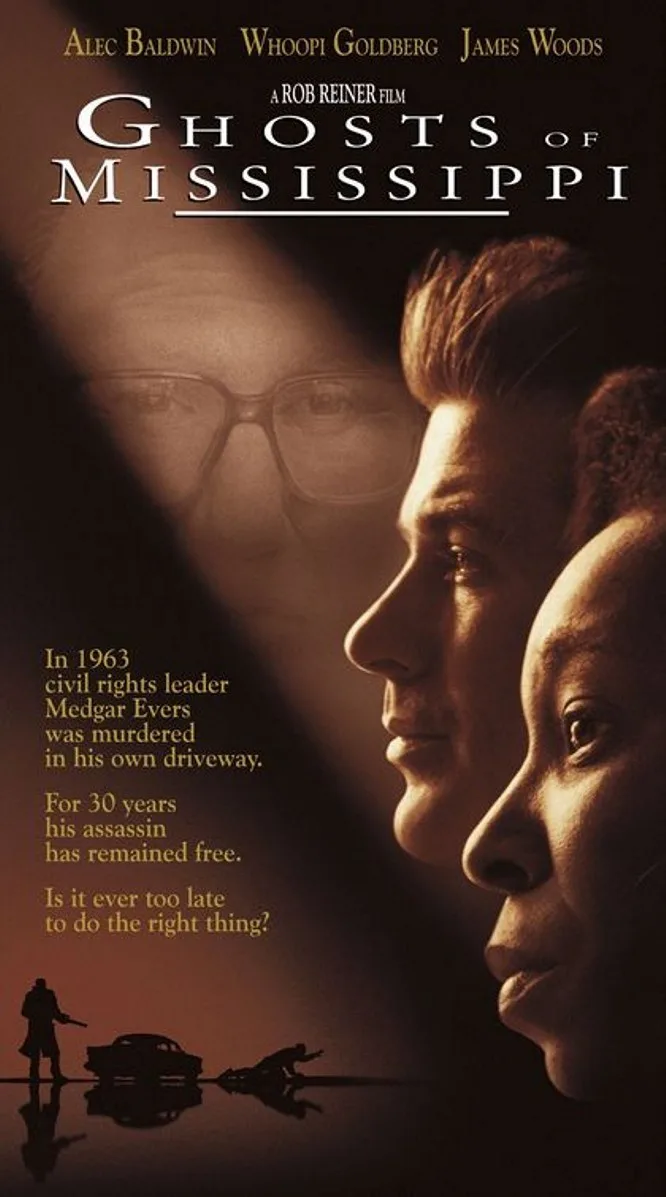

Allof this is remembered with fidelity in Rob Reiner’s “Ghosts of Mississippi,”which tells the story of how a white prosecutor named Bobby DeLaughterre-opened the case in 1989 and eventually won a conviction against De LaBeckwith, who had spent the intervening years all but openly boasting about thekilling. Justice was finally served, to the relief (and amazement) of MyrlieEvers, Medgar’s widow, who sought all that time to bring her husband’s killerback into a courtroom.

Thisis a moving story, but it’s not a particularly compelling one in “Ghosts ofMississippi,” which plays like a TV docudrama and doesn’t generate theemotional intensity of such similar films as “Mississippi Burning” and “A Time To Kill.” Maybe it focuses on the wrong characters. The movie is seen throughthe eyes of DeLaughter (Alec Baldwin), who does his job well, and at somehazard–but his story is more of a legal procedural than a human drama. Theemotional center of the film should probably be Myrlie Evers (Whoopi Goldberg),who cradled her bleeding husband as he died that night, her weeping andfrightened children around her. But the role is underwritten to such a degreethat Myrlie never really emerges except as an emblem, and Goldberg plays herlike the guest of honor at a testimonial banquet. There’s no juice.

That’spartly Goldberg’s fault (this is not one of her better performances) but mostlythe fault of the filmmakers, who see their material through white eyes and usethe Myrlie character as a convenient conscience. Many of the scenes betweenDeLaughter and Mrs. Evers take place on the telephone, where the white lawyerreports that he’s doing the best he can, and the widow says “uh–huh,” anddoubts it. It doesn’t help that a crucial piece of evidence–thecourt-certified transcript of the original trial–seems to be missing, andDeLaughter is stymied for months before Mrs. Evers belatedly reveals that shehas it. (She says she didn’t trust it to anyone; hadn’t she heard of Kinko’s?).

Themovie’s most convincing character is De La Beckwith, the old racist, who ismade by that splendid actor James Woods into a vile, damaged man. Woods goesfor broke. De La Beckwith has a shifty, squirmy hatefulness; being a racist isa source of great entertainment to him, and he expresses his ideas with glee.We detest the character from beginning to end, but we react to it; the movie’sother characters are more emblems than people.

There’san underlying issue here. This movie, like many others, is really about whiteredemption. As Godfrey Chesire points out in his review in Variety, “Whenfuture generations turn to this era’s movies for an account of the strugglesfor racial justice in America, they’ll learn the surprising lesson that suchbattles were fought and won by square-jawed white guys.” Maybe Hollywood believesthat racially-charged plots play better at the box office with white stars inthe leads. It isn’t enough that white southerners practiced segregation andracism for decades; now they get to play the heroic roles in their dismantling.Movies like this underline the rarity of work like Tim Reid’s “Once Upon a Time. . . When We Were Colored,” which portrayed a self-sufficient black southerncommunity that had its own worth and reality apart from white society.

In“Ghosts of Mississippi,” white society is seen perceptively. We learn onceagain about the establishment’s White Citizens Councils and their shady linkswith the Ku Klux Klan. The movie uses DeLaughter’s first wife, Dixie (VirginiaMadsen), as a link to the past through her father, “the most racist judge inMississippi.” We learn that the newly-enlightened white community has ghosts itprefers to keep in the closet: “You’re dealing with the past. In the state ofMississippi, that’s not where you want to be.” Old-timers use revealing word choices,referring to Evers as “the civil rights leader that got himself shot.” All ofthat is well done, but where are the black people? Myrlie Evers functions as aconscience who is usually off-screen. Other black characters are found mostlyin crowd scenes. What we get, really, is self-congratulation: Whites may havebeen responsible for segregation, but by golly, aren’t we doing a wonderful jobof making amends? Alan Parker’s “Mississippi Burning” (1983) was criticized formaking white FBI agents into heroes of the civil rights era when the real FBIwas conspicuous by its lack of enthusiasm for that assignment. But that filmpaid its way with great performances and tremendously moving drama. “Ghosts ofMississippi” generates nowhere near as much passion. It closes a chapter inhistory, but scarcely brings it to life.