“A Time to Kill,” based on the first novel by John Grisham, is a skillfully constructed morality play that pushes all the right buttons and arrives at all the right conclusions. It begins with the brutal rape of a 10-year-old black girl by two rednecks in a pickup truck. The girl’s father kills the rapists in cold blood on their way to a court hearing and cripples a deputy in the process. The local white liberal lawyer agrees to defend him. The Klan plots to gain revenge. Good of course triumphs–but we’ll get back to that in a moment.

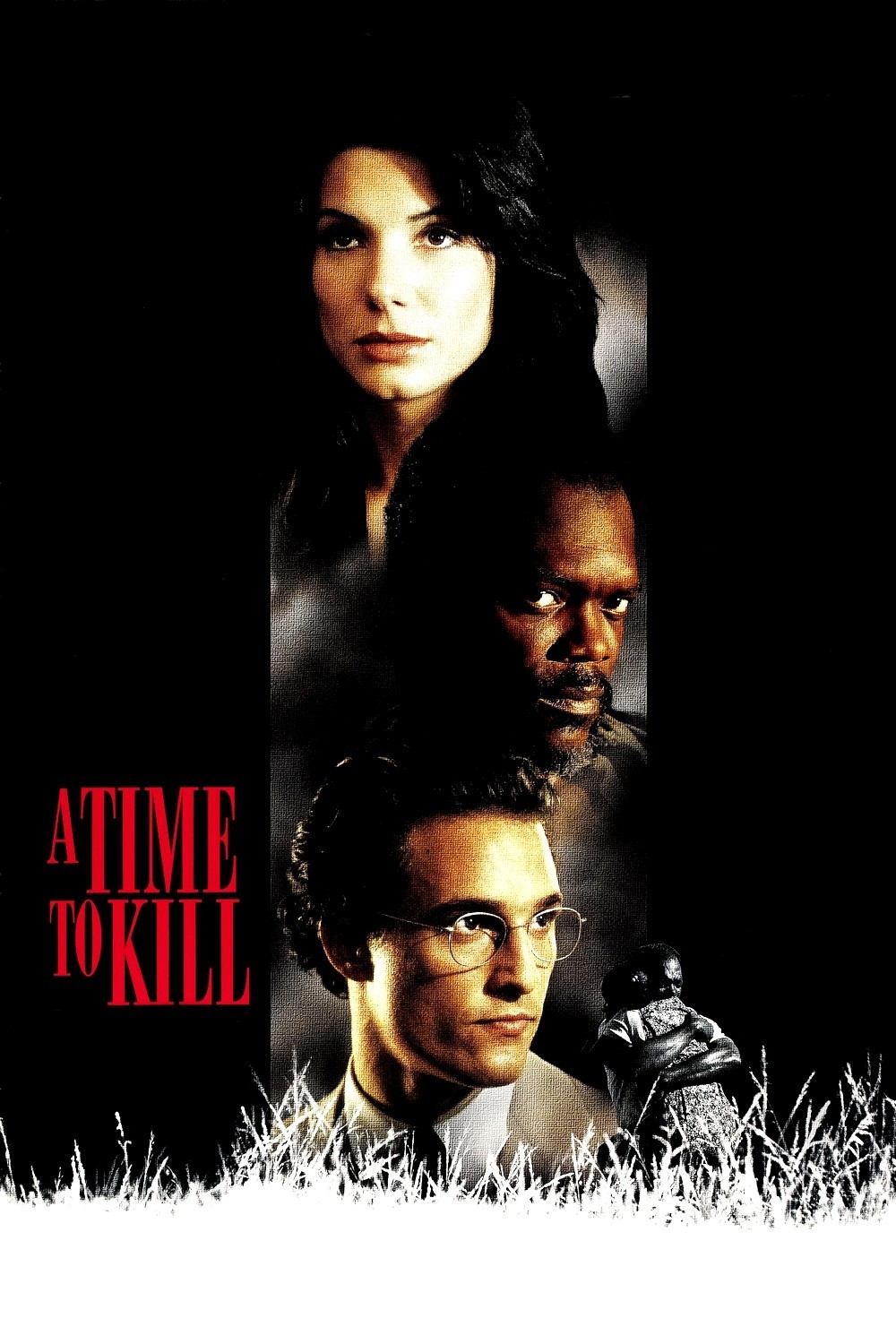

I was absorbed by “A Time to Kill,” and found the performances strong and convincing, especially the work by Samuel L. Jackson as Carl Lee Hailey, the avenging father, and Matthew McConaughey as Jake Brigance, the lawyer. This is the best of the film versions of Grisham novels, I think, and it has been directed with skill by Joel Schumacher.

But as I watched the film, other thoughts intruded. Grisham recently attacked director Oliver Stone, alleging that Stone’s “Natural Born Killers” inspired drugged-out creeps to murder a friend of Grisham’s. Stone should be sued by the victim’s family, Grisham said, offering the theory that “NBK” was to blame under product-liability laws.

Well, Grisham is a lawyer, and lawyers exist to file suits. But one might reasonably ask whether the creeps would have committed the murder without taking the drugs. One might also ask if Grisham forfeits his right to moral superiority by including a subplot in “A Time to Kill” that gives the Ku Klux Klan prominence and a certain degenerate glamor. Yes, Klan members are the villains. But to a twisted mind, their secret meetings and corn-pone rituals might be appealing.

However, if you leave out everything that might inspire a nut, you don’t have a movie left–or a free society, either. Artists cannot hold themselves hostage to the possibility that defectives might misuse their work. Grisham should simply be honest enough to recognize that he does the same things he says Stone shouldn’t do.

As a story, “A Time to Kill” works effectively. (I will have to discuss certain plot points, so be warned.) Everyone in the county knows Carl Lee Hailey killed the two men who raped his daughter, and many of them share his feelings. (Even the crippled deputy blurts out, under oath, that he would have done the same thing.) But can a black man get a fair trial after murdering two white men, even in the “new” South? The movie milks this question for all it’s worth, which isn’t much, unless the average audience thinks Hollywood will allow Klan thugs to prevail over the hero. “You’re my secret weapon,” the black man tells his white lawyer. “You see me the way the jury will see me. What would it take, if you were on the jury, to set me free?” As Brigance prepares his case, crosses are burned on lawns, anonymous phone calls are made, and his wife (Ashley Judd) moves their family to safety.

That’s well-timed to clear space for another character, the young lawyer Ellen Roark (Sandra Bullock), a rich Northerner who studied law at Ole Miss and wants to be Brigance’s unpaid aide. He discourages her, but she turns up with useful leads, and he needs someone to help him counter the expert local district attorney (Kevin Spacey).

The movie climaxes with the obligatory courtroom scenes. Brigance’s summation is well-delivered by McConaughey, but his tactics left me feeling uneasy. He describes the sadistic acts against Hailey’s daughter in almost pornographic detail, then asks the jury, “Now imagine she’s white.” That’s an odd statement, implying that the white jury wouldn’t be offended by the crimes if the victim was black.

Yet the movie itself has trouble imagining its black characters. The subplots involve mostly Brigance’s white friends and associates: his alcoholic old mentor (Donald Sutherland), his alcoholic young mentor (Oliver Platt), his alcoholic expert witness (M. Emmet Walsh), his secretary (Brenda Fricker), his wife (Judd), and his unpaid assistant (Bullock). Another strand involves the plotting of the Klan, led by the vicious Cobb (Kiefer Sutherland). There are a few scenes involving the NAACP’s legal defense people, who persuade the local pastor to hold a fund-raiser for Hailey’s legal defense–but insist the money be used for a black lawyer. Hailey turns them down, in an awkward sequence intended, I think, to equate the NAACP lawyers with figures like the Rev. Al Sharpton.

One wonders why more screen time wasn’t found for black characters like Hailey’s wife. Maybe the answer is that the movie is interested in the white characters as people and the black characters (apart from Carl Lee Hailey) as atmosphere. My advice to the filmmakers about the black people in town: Try imagining they’re white.

The ending left me a little confused. (Again, be warned I’ll discuss plot points.) A child bursts from the courtroom and tells the waiting crowd that Hailey is “innocent.” A cheer goes up. There is joy and reconciliation. But hold on. Hailey’s own defense admits he killed those men. The jury probably found him not guilty by reason of temporary insanity. But “innocent?” Maybe the device of the shouting child was used to avoid such technicalities, and hasten the happy ending.

This review doesn’t sound much like praise. Yet I recommend the film. What we have here is an interesting example of the way the movies work. “A Time to Kill” raises a lot of questions, but they don’t occur while you’re watching the film. The acting is so persuasive and the direction is so fluid that the material seems convincing while it’s happening. I was moved by McConaughey’s speech to the jury, and even more moved by an earlier speech by Jackson to McConaughey. I cared about the characters. And then I walked out, and got to thinking about the movie’s choices and buried strategies. And I read about Grisham’s attack on Stone. And I thought, let he who is without sin …