“Look into my eyes so you know what it’s like to live a life not knowing what a normal life’s like.”

Among its many cathartic functions, art provides us with a safe space to articulate our experiences of trauma that we’d normally avoid discussing out loud. Few recent films have portrayed this as indelibly as Destin Daniel Cretton’s 2013 masterwork, “Short Term 12,” which was based on the writer/director’s own experiences of working with troubled teens at a foster care facility. The scene quoted above in which young Marcus (Lakeith Stanfield) performs his achingly personal rap song about not having a place in the world has more power than the entirety of “Foster Boy,” Youssef Delara’s frustrating new courtroom drama. There’s no question the picture is fraught with good intentions. It was produced by Peter Samuelson, who runs a nonprofit that provides foster children with college readiness programs, and it was written by Jay Paul Deratany, a lawyer with an impressive legacy of targeting foster care negligence. A skim through the film’s official site offers ample insights into the insidiously corrupt for-profit foster care industry, which views the wrongful placement of children in abusive homes as an incentive for making more money.

This urgent material is obviously worthy of being given the filmic treatment, but as Roger Ebert famously wrote, it’s not what a film is about, but how it is about it. Naming this movie “Foster Boy” is as misleading as naming Peter Farrelly’s widely maligned Best Picture-winner “Green Book,” since both films fail to truly be about what their titles suggest. It’s reasonable to assume that the main character of Delara’s film would be Jamal (a woefully underutilized Shane Paul McGhie), a man wracked with PTSD from the years of abuse he endured in nightmarish foster homes that robbed him of his childhood. He intends on suing the social services corporation that willfully turned a blind eye to his suffering while lining their pockets in the process. Alas, Judge Taylor (Louis Gossett Jr.) deems Jamal unfit to represent himself in court, and decides on the spur of the moment to assign corporate lawyer Michael (Matthew Modine) to work for him pro bono. It’s not long before Michael’s scenes dominate the screen time, rendering Jamal’s wrenching backstory—glimpsed only in disjointed flashbacks—as an afterthought.

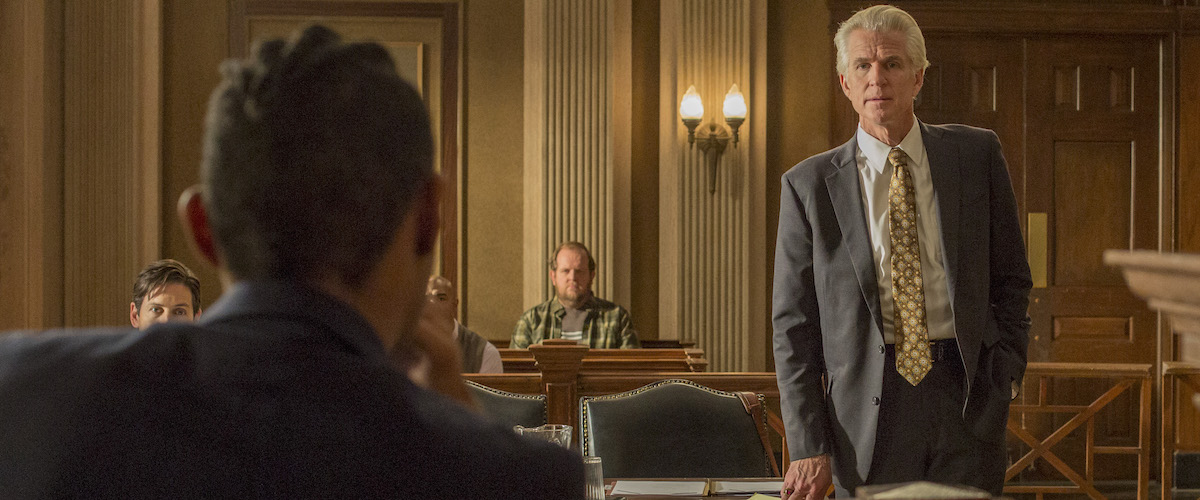

Yes, this is yet another contrived would-be crowdpleaser about an insufferable white man whose unlikely bond with a Black man inspires him to become a better person. Though I don’t recall the word “racist” being uttered once throughout the course of the picture, that is what Michael unmistakably is from the get-go, as he dismisses Jamal as a “thug” purely on the basis of his appearance, while condescending to a Black colleague, Keisha (Lex Scott Davis), after ignoring her for months. Michael also has a curious form of OCD he demonstrates in his first scene, as he adjusts four white cups on his kitchen counter, an illustration of white privilege worthy of a Wayans Brothers comedy. This becomes an inadvertently amusing running gag when we later see him adjusting a painting in his ex-wife’s home without being asked. Even more perplexing is Michael’s ineptitude as a lawyer, which makes one wonder how he obtained such high-powered corporate clients in the first place. He initially puts forth no effort to understand or empathize with Jamal, tossing him on the witness stand and badgering him with sensitive questions until the poor soul snaps. So spiteful and sloppy is his courtroom conduct that he even forgets to authenticate documents before introducing them as evidence.

And yet, we’re supposed to grow to like Michael because his prejudice is contrasted with that of the villains at social services, who are portrayed as broadly as the evil liberals in “God’s Not Dead.” Only when confronted by their sociopathic vice president of claims, Pamela (Julie Benz), does Michael abruptly change his tune, arguing that “kids aren’t products,” as if taking on this case will suddenly redeem him for all the soulless corporations he’s defended in the past, enabling him to amass his fortune. In light of the profound reckoning with our nation’s history of systemic racism that has characterized this year, triggered in part by a pandemic that has primarily impacted people of color, it’s especially dated to have a white lawyer deliver an Atticus Finch-style speech where he comforts his Black client by “wrapping him with” the U.S. Constitution, a document replete with loopholes that ensure racial subjugation. Rather than explore the complex challenges of being Black in America, the film spends far too much time focusing on the hackneyed plot developments that lead to Michael’s endangerment. In order to dissuade him from continuing with the case, Pamela and her sinister henchmen resort to the mischief of any run-of-the-mill shadow organization: they strip Michael of his corporate clients, jam his phone, try running him over with a car, etc. They even manage to stick Jamal in the same cell as his rapist, an eye-rolling twist that would’ve been more potent had either character been sufficiently developed in the script.

By the time we finally arrive at the moving scene where Jamal opens up about the crimes committed against him, performing verses he had written in journals as a mode of coping with the trauma, it is too little too late. In a maddening flourish, Jamal’s tearful monologue is accompanied by the hokey swell of a non-diegetic score, a layer of artifice that does little more than distract from how effective an actor McGhie is in conveying his character’s raw agony on his own terms. After a pat resolution in which all the formulaic cogs click into place at the expected time, we are faced with a title card informing us that of the half a million children currently in foster care, over forty percent of them will end up “homeless, incarcerated or die within three years of leaving the foster care system.” These children are sorely deserving of having this injustice be addressed in a film that doesn’t upstage their plight with the hollow heroics of a white savior. Had the filmmakers put forth the effort to view the story through Jamal’s eyes, they may have had a worthy cinematic counterpart to their noble off-camera achievements.

In theaters & VOD on September 25th