“Extraordinary Measures” is an ordinary film with ordinary characters in a story too big for it. Life has been reduced to a Lifetime movie. The story, based on fact, is compelling: Two sick children have no more than a year to live when their father determines to seek out a maverick scientist who may have a cure. This is “Lorenzo's Oil” with a different disease, Pompe disease, although it fudges the facts to create a better story.

The film centers on two dying children, ages 9 and 7. In real life, most children with Pompe die before age 2, and those in the real story were 15 months and 7 days old when they got sick, and 5 and 4 years old when they began treatment.

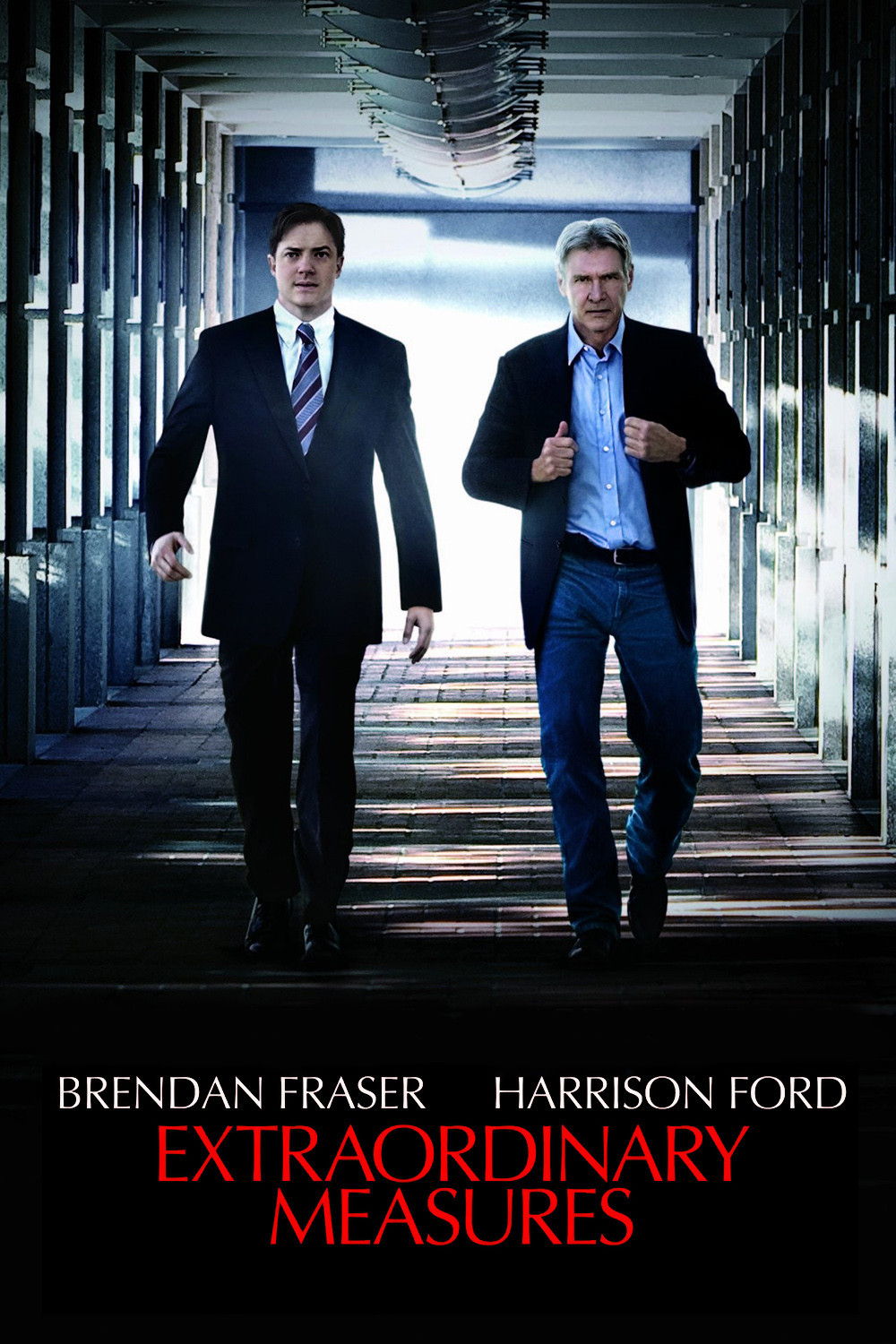

With children that young, the drama would have focused on the parents. By making Megan Crowley (Meredith Droeger) a wise and cheerful 9-year old, “Extraordinary Measures” improves her as a story element. Her father is John Crowley (Brendan Fraser), an executive at Bristol-Myers Squibb. Her mother is Aileen (Keri Russell). Neither character is developed any more deeply than the story requires. Their personal relationship is defined by their desperation as the deadlines for their children grow nearer.

Crowley discovers on the Internet a professor at the University of Nebraska named Dr. Robert Stonehill (Harrison Ford). He’s working on a controversial cure for Pompe that the medical establishment rejects, and when he won’t return messages, Crowley impulsively flies to Nebraska to confront him.

Dr. Robert Stonehill doesn’t exist in real life. The Pompe cure was developed by Dr. Yuan-Tsong Chen and his colleagues while he was at Duke University. He is now director of the Institute of Biomedical Science in Taiwan. Harrison Ford, as this film’s executive producer, perhaps saw Stonehill as a plum role for himself; a rewrite was necessary because he couldn’t very well play Dr. Chen. The real Chen, a Taiwan University graduate, worked his way up at Duke from a residency to professor and chief of medical genetics at the Duke University Medical Center. He has been mentioned as a Nobel candidate.

I suspect Dr. Chen might have inspired a more interesting character than “Dr. Stonehill.” The Nebraskan seems inspired more by Harrison Ford’s image and range. He plays the doctor using only a few spare parts off the shelf. (1) He likes to crank up rock music while he works. (2) He doesn’t return messages. (3) He’s so feckless he accidentally hangs up on Crowley by pulling the phone off his desk. (4) He likes to drink beer from longneck bottles in a honky-tonk bar and flirt with the waitress. (5) “I’m a scientist, not a doctor,” he says. He’s not interested in Pompe patients, only the chemistry of the disease.

This becomes tiresome. Later he becomes invested in the Crowleys, but of course he does. They hope to fund a high-tech startup and deal with venture capitalists whose scenes are more interesting than many of the medical ones. Contrast this with the character of Augusto Odone, played by Nick Nolte in “Lorenzo’s Oil” (1992) — a self-taught parent who discovers his own cure for a rare nerve disease. Ford is given no lines that suggest depth of character, only gruffness that gradually mellows.

The film also fails to explain that the cost of the medication is $300,00 a year for life, which limits its impact in the United States because many American insurance companies refuse to pay for it. According to Wikipedia, “The vast majority of developed countries are providing access to therapy for all diagnosed Pompe patients.”

Make no mistake. The Crowleys were brave and resourceful, and their proactive measures saved the lives of their children — and many more with Pompe. This is a remarkable story. I think the film lets them down. It finds the shortest possible route between beginning and end. It also sidesteps the point that the U.S. health-care system makes the cure unavailable to many dying children; they are being saved in nations with universal health coverage.