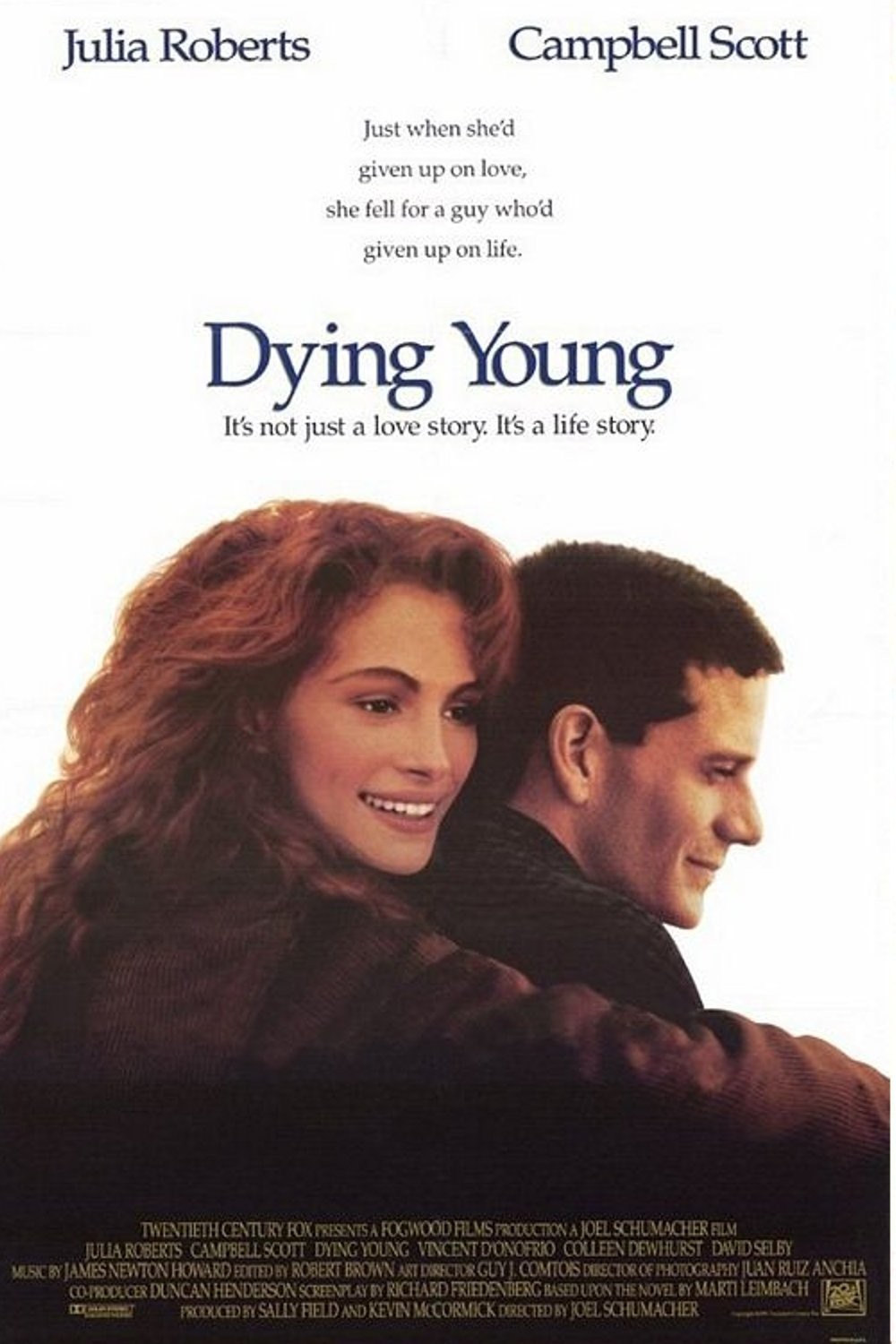

“Dying Young” is a long, slow slog of a movie, up to its knees in drippy self-pity as it marches wearily toward its inevitable ending. And when I describe the ending as inevitable, by that I do not mean that the hero of “Dying Young” actually dies young. The movie doesn’t have that much imagination.

Julia Roberts stars as Hilary, a young woman from Oakland, Calif., who answers a classified ad with a Nob Hill address in San Francisco. The ads calls for a “young and attractive” woman with “some” nursing experience, and as the young and attractive woman trudges up Nob Hill in her red miniskirt, we get the feeling that two days as a candy striper might be enough experience.

We are correct. Roberts is hired by young Victor Geddes (Campbell Scott), who has been battling leukemia half of his life and needs someone to help him get through his next course in chemotherapy. Roberts takes the job, and as her patient vomits and shivers and writhes in pain, she helps the best she can. At first she fears she’s not equal to the task, but she is, of course, and eventually the two slip away and rent a cottage in northern California, where they fall in love while he enjoys a remission.

Their love is not, however, a great romantic saga; “Love Story” was a substantially better version of the same story. One of the problems is that Victor is a drip: a whiny, manipulative martyr with the kind of flat, husky voice I always associate with Henry the serial killer. Hilary is also a little out of focus. As played by Roberts, she knows all the words but we never hear the music. Even the big dramatic moments are curiously muted, and people are forever disappearing into shadows (one of Victor’s exits looks stolen directly from “The Phantom of the Opera”).

If the plot is predictable, maybe it’s because “Dying Young” is a virtual rewrite of the formula of “Pretty Woman,” Roberts’ entertaining 1990 movie. Once again we have the rich, knowledgeable man taking the uneducated working-class girl under his arm, wining and dining her, giving her educational lectures, using his money to buy her love. Only the disease has changed, with leukemia substituting for soul sickness. The two movies have similar no-sex agreements, which are similarly broken, and moments in which the rich, smart man realizes he can learn something about himself from this simple woman of the people.

There is an agonizingly awkward subplot this time, involving Vincent D'Onofrio as a friendly local handyman. Will Roberts choose him instead of remaining loyal to her dying lover? I gather that in one early version of the movie she actually did, but audiences hated her for it, and so we get the current ending, with lachrymose pledges of eternal love followed, so help me, by a new day a-dawning.

That sunrise aside, the whole movie seems under a pall.

Disease and death need not be this funereal. Remember “Longtime Companion,” with its wonderful scenes of loyalty and courage? “Dying Young” doesn’t really feel any of its emotions – it’s a cynically constructed tearjerker that’s so artificial and contrived I felt embarrassed watching it.

It’s also sloppy filmmaking. Elements are thrown in for effect but never thought through. Exactly how does the figure of the father change so dramatically, from indifference to concern, in his two big scenes? What is the function of the butler in the story? Do Roberts and D’Onofrio feel anything at all for one another? What about that neighbor woman who turns up her nose at the young couple? Was she included for any other purpose than to be shocked, later, when Victor runs naked into the dawn? Her reaction is so predictable that as he was running I was counting the seconds until she appeared.

Many of these flaws could be overlooked if the central characters were more likable (“Pretty Woman” had gaping holes in it, but so what?). What bothered me most of all was the performance by Campbell Scott, who simply never generated enough warmth and sympathy to explain why Julia Roberts would want to love him. And Roberts herself, perhaps falling under the same depressing shroud, lacks the heart and bouncy humor that were so important to “Pretty Woman.” Dying young is one thing. These characters seem to be dying together.