I read Love Story one morning in about fourteen minutes flat, out of simple curiosity. I wanted to discover why five and a half million people had actually bought it. I wasn’t successful. I was so put off by Erich Segal’s writing style, in fact, that I hardly wanted to see the movie at all. Segal’s prose style is so revoltingly coy — sort of a cross between a parody of Hemingway and the instructions on a soup can — that his story is fatally infected.

The fact is, however, that the film of Love Story is infinitely better than the book. I think it has something to do with the quiet taste of Arthur Hiller, its director, who has put in all the things that Segal thought he was being clever to leave out. Things like color, character, personality, detail, and background. The interesting thing is that Hiller has saved the movie without substantially changing anything in the book. Both the screenplay and the novel were written at the same time, I understand, and if you’ve read the book, you’ve essentially read the screenplay. Nothing much is changed except the last meeting between Oliver and his father; Hiller felt the movie should end with the boy alone, and he was right. Otherwise, he’s used Segal’s situations and dialogue throughout.

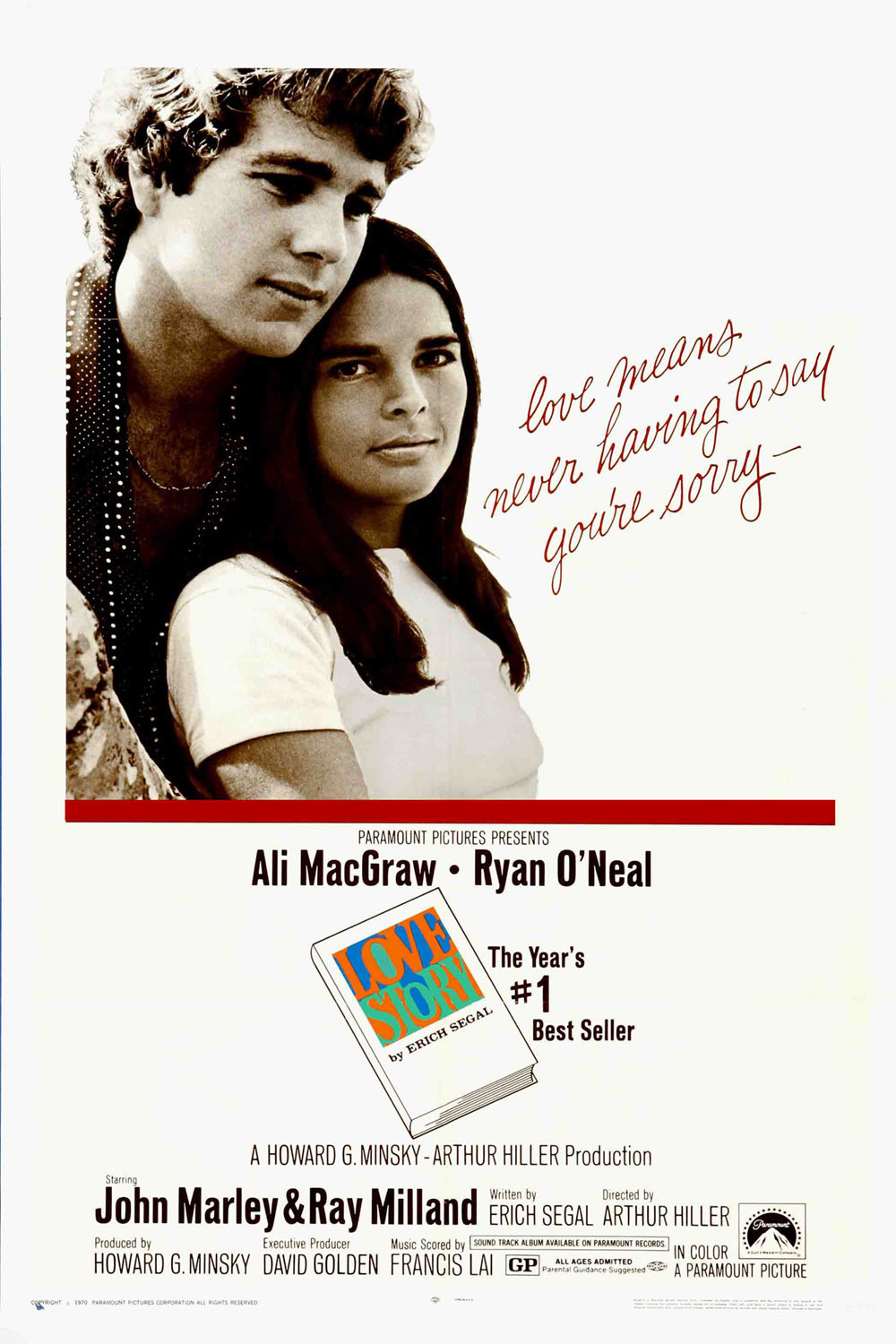

But the Segal characters, on paper, were so devoid of any personality that they might actually have been transparent. Ali MacGraw and Ryan O'Neal, who play the lovers on film, bring them to life in a way the novel didn’t even attempt. They do it simply by being there, and having personalities.

The story by now is so well-known that there’s no point in summarizing it for you. I would like to consider, however, the implications of “Love Story” as a three-, four-or five-handkerchief movie, a movie that wants viewers to cry at the end. Is this an unworthy purpose? Does the movie become unworthy, as Newsweek thought it did, simply because it has been mechanically contrived to tell us a beautiful, tragic tale? I don’t think so. There’s nothing contemptible about being moved to joy by a musical, to terror by a thriller, to excitement by a Western. Why shouldn’t we get a little misty during a story about young lovers separated by death?

Hiller earns our emotional response because of the way he’s directed the movie. The Segal book was so patently contrived to force those tears, and moved toward that object with such humorless determination, that it must have actually disgusted a lot of readers. The movie is mostly about life, however, and not death. And because Hiller makes the lovers into individuals, of course we’re moved by the film’s conclusion. Why not?