“He is survived,” the obituaries sometimes say, “by his longtime companion.” The phrase is taken by everybody to mean “lover,” but newspapers prefer the euphemism, and only in the age of AIDS have they even finally admitted that homosexuals do not live, or die, alone.

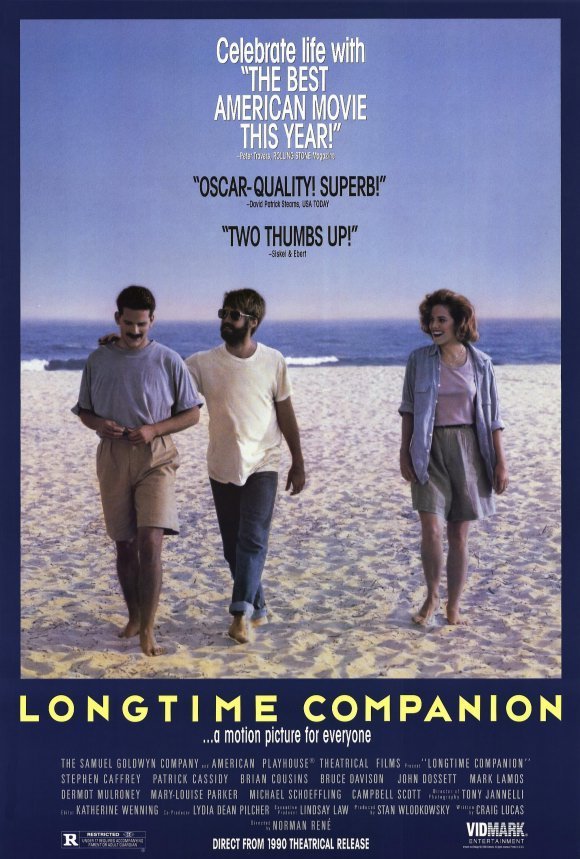

Norman Rene’s “Longtime Companion” is a film that begins on the day when an obscure story in the New York Times first mentions a disease that seems to be striking homosexual men, and it ends after AIDS has profoundly affected all of their lives – mostly, but not entirely, for the worse.

That first small cloud on the horizon was a story about a “gay cancer” that doctors were reporting among some of their homosexual patients. Within a few months, the Village Voice was providing in-depth reporting on the “gay plague,” which eventually was named AIDS. But at the beginning, the characters in the story have difficulty in believing that a disease could seem to single them out.

The movie has been written by Craig Lucas as a series of scenes, sometimes separated by months or years, in the lives of several ordinary homosexual men, and it is the very everyday quality of their lives – work and home, love and cooking and weekends – that provides the bedrock for this film. The emphasis is on the notion of “longtime.” During the course of the movie some characters will fall in love and others will break up, but most of them will be steadfast in their friendships and they will stand by each other in a series of crises. Of course others simply disappear when AIDS arrives to interfere with their personal priorities, but not everyone is a saint, and some of the events in this film require, or inspire, a quality of sainthood.

The movie is told in chronological order, so that at every moment we know as much as the characters do about AIDS. At first they can’t believe it at all. Then they can’t believe it could strike anyone they know – or themselves. Then they begin to ask themselves uneasy questions about less-than-prudent episodes in their lives: Are long-forgotten indiscretions about to come back and take a deadly toll? Is AIDS the revenge of the past? When a friend gets sick, it is hard to ask what the matter is, easy to pretend it is “something else.” A friend loses weight, and inevitable questions arise. Lovers ask each other hard questions about fidelity, and do not always get honest answers. One by one, over the period of years, the circle of friends grows smaller. Of course many will survive, but there seems to be no sensible pattern in who is chosen, and no guarantee that a man will not care for his friend only to need help himself before long. Few films have done a better job of illustrating the virtue of “visiting the sick” – that cardinal act of mercy most neglected in an America that likes to let hospitals take care of that sort of hard work.

The central scene in the film – one of the most emotionally affecting scenes in any film on dying – involves Bruce Davison as the lover of a dying man. The struggle has been long and painful, but now it is almost over, and what Davison has to do is hold the hand of his friend and be with him when he dies. The fight has been so brave that it is hard to end it. “Let go,” Davison whispers. “It’s all right. You can let go now.” The scene plays for a long, quiet time, and it is about the absolute finality of death, but it is also about why we are alive in the first place. Man is the only animal that knows it will die. This scene shows how that can be the source of courage and spiritual peace.

One of the particular strengths of “Longtime Companion” is that it does not identify its characters only through their sexual preferences. It would seem bizarre to watch a movie in which heterosexual men were defined only by the fact that they like to sleep with women – but many films about gays have made the opposite error, and limited their characters as a result. “Longtime Companion” is about friendship and loyalty about finding the courage to be helpful and the humility to be helped.