There’s a 1950s genre of films that asked to be decoded through a gay lens. They undermined the conventional view of straight, middle-class American life, inviting the irony of outsiders (homosexual or not). Their glamorous, overwrought heroines were role models for the emerging camp sensibility. Douglas Sirk’s melodramas (among them “Imitation of Life,” “Written on the Wind” and “All That Heaven Allows”) are at the head of this category, and Todd Haynes’ “Far From Heaven” (2002) was a film that moved Sirk’s buried themes into the foreground. What made Sirk a great director is that his stories were sappy in a way that was subversive to the restrictive values of the time.

The whole point, though, was that his movies never copped to what they were doing. They didn’t wink or nudge or engage in Wildean double entendres (well, maybe sometimes, as when Rock Hudson is told it’s time to get married and says, “I have trouble enough just finding oil”). Sirk was as sincere about his surface story as he was about his subtext, and that’s why his movies still function as real melodrama and not as camp. The strength of “Far From Heaven” is its complete earnestness; it isn’t a 2002 satire of Sirk, but wants to be the 1957 movie he couldn’t make. We can smile at the story’s hysteria about homosexual and interracial romance, but those were not laughing matters in the 1950s, and the movie honors that.

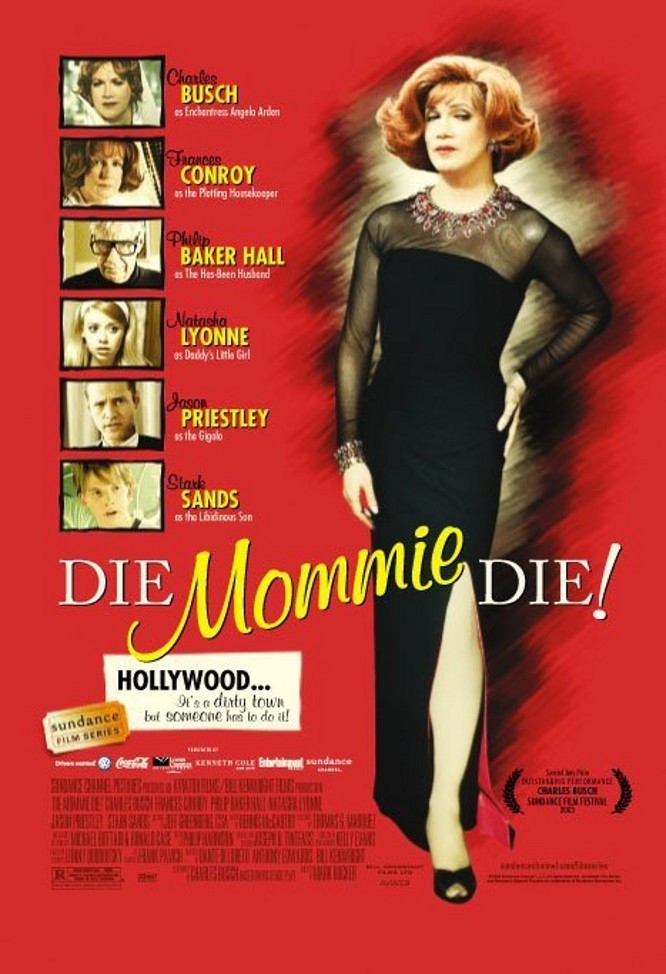

The problem with “Die, Mommie, Die,” a drag send-up of the genre, is that it spoils the fun by making it obvious. While it is true that late in their careers Joan Crawford or Bette Davis sometimes seemed like drag queens, they were not, and would have been offended by the suggestion. The lead in “Die, Mommie, Die” is Charles Busch, a professional drag queen, and the whole point of the movie is precisely that he is a drag queen.

There is a crucial difference between a drag queen and a female impersonator. Impersonators want to be “read” as women, and may sincerely think of themselves as women. That would seem to be the case with Jaye Davidson’s character in “The Crying Game.” The drag queen, on the other hand, wants you to know he is a man. Charles Busch is in that category; he looks like a man in drag, and that’s the point. The performance consists of a send-up by a gay man of a straight woman, and the story is a lampoon of cherished heterosexual conventions.

It is also, of course, a comedy, and I know I’m getting awfully serious about something that intends to be silly and trashy. But I’m trying to explain to myself why it didn’t work, and I think it’s because drag queens are no longer funny just because they’re drag queens; we’ve lost the nervousness about gender that once made us need to laugh at a man in drag. The material started out as a play, and probably worked better then, because a simpatico audience could make it an event.

The story stars Busch as Angela Arden, a failed singer married to a failing Hollywood producer named Sol Sussman (Philip Baker Hall). He makes bad movies but has lost the touch of making a profit on them. During his latest debacle in Europe, she’s had an affair with the young stud Tony Parker (Jason Priestley). Now she wants a divorce from Sol, but nothing doing: “We’re a famous couple, Angela, and we’re going to stay together.” Completing the Sussman household are their maid Bootsie Carp (Frances Conroy), their slutty daughter Edith (Natasha Lyonne), and their gay pothead son Lance (played by an actor whose name may really be Stark Sands, although that sounds like a retro product of the Rock-Troy-Tab name generator).

Angela has a singing engagement in a third-rate resort. Sol cancels it in a fit of rage. Angela strikes back. Sol has been complaining loudly (and, because this is the great Philip Baker Hall, convincingly) about his constipation, and so she poisons his suppository, ho, ho. Many complications ensue, all provoking Angela to run amok through the gamut of emotions.

Some of the dialogue and many of the gags are in fact funny. But the movie’s reason for being is Busch’s drag performance, and I didn’t find anything funny because he was a man in drag. What was funny worked despite that fact. A woman in the role might have been funnier, because then we wouldn’t have had to be thinking about two things at once: The gag, and the drag.

Imagine a very good actor who is also a very good juggler. You admire his versatility, but during “Hamlet” you’d want him to put down his balls during the soliloquies.