Echoes of Folk Horror, “The Babadook,” and even “Under the Skin” weave through Benjamin Barfoot’s chilling study of the denial that often unfolds after the sudden loss of a loved one. When someone we care about dies unexpectedly in something like a car crash, it fractures reality, an idea that horror has leaned into for years. There’s a whole subgenre, especially lately, of what could be called “Grief Horror.” Still, Barfoot avoids the traps of this classification by valuing imagery over explanation, leading to a film that might confuse some people but haunt them nonetheless.

The young Rupert Turnbull is excellent as Isaac, a boy who suffers the unimaginable loss of his father, James (Charles Aitken), only a short time after losing his mother. Now orphaned, he’s essentially stranded at home deep in the countryside with a stepmother named Laura (Julia Brown), who makes it clear that she never planned on being a single mother. She fell in love with a man and accepted her role as a stepmom, but now everything has changed, and she’s not sure if she even wants to be Isaac’s legal guardian, considering turning him over to the state and life in foster homes. She drinks to numb the pain and turns to a divorced friend named Robert (Nathaniel Martello-White) for comfort.

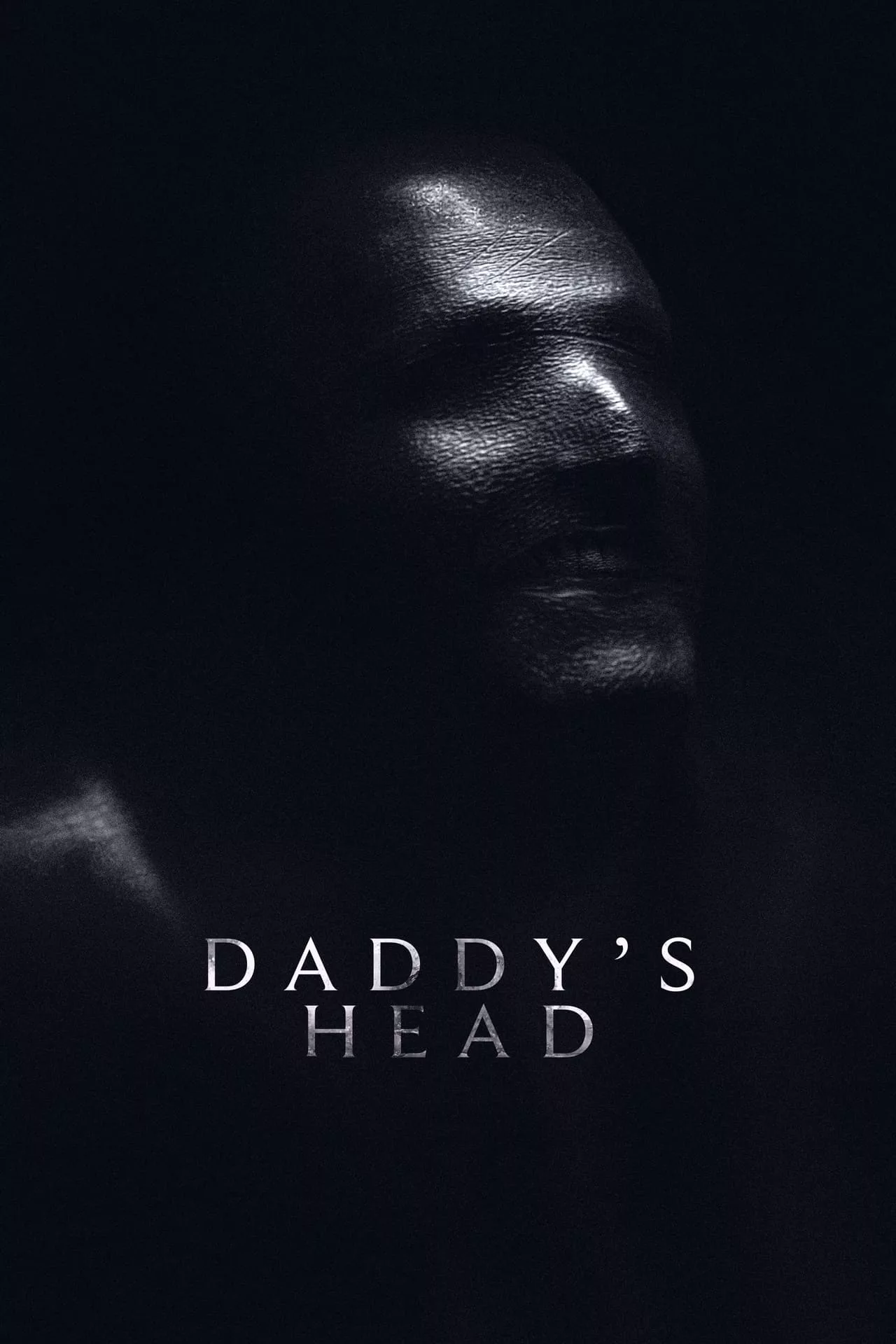

Into this emotionally damaged landscape drops something impossible, perhaps quite literally. With smoke in the woods and lights at night, there’s a reading of “Daddy’s Head” that what unfolds for James and Laura is alien in nature, but one of the reasons I admire the film is its refusal to connect all of its dots. Suffice it to say that Laura and Isaac come back from James’s funeral to find something under the table. It zips out of the room and through a window into the miles of foreboding woods surrounding them.

Laura presumes it was an animal, but Isaac starts to see this dark creature in the most unexpected places, including an AC vent in his room in the film’s most terrifying sequence. Everyone finds what looks like a witch’s home in the woods, adding to the fable/folk aspects of Barfoot’s story. Thousands of years of storytelling make it clear that nothing good lives in a place like that, but Isaac refuses to give up on his investigation for one major reason: Whatever this thing is, it has Daddy’s head.

The lengths to which we will go—or the denial that we’re willing to embrace—to spend more time with a deceased loved one has been a foundational theme of horror since the beginning. What’s the price to pay for reversing death? Barfoot plays with this theme in a way that feels emotionally raw, ably assisted by great performances from Turnbull and Brown. The young Isaac provokes our empathy for his situation without ever resorting to melodrama and sells the blend of terror and hope gripping his character. He knows this isn’t right. But it’s Dad! And Brown conveys the weight of grief over her new responsibility as a mother, warped further when she starts to suspect that Isaac may hide a murderous secret himself.

Clearly, there’s a lot to unpack in “Daddy’s Head.” Still, it all works primarily because of Barfoot’s oversight of the film’s sharp technical elements, including fantastic production design, cinematography, and editing. While I wish he had one or two fewer jump scares and a bit more refined CGI, what works here is the film’s overall mood more than individual moments. Most effectively, Barfoot and his team turn this cold, remote estate into a character—returning to it provides none of the standard warmth of a happy home. We can feel the chill in the air. He uses recurring imagery well, often employing circles and straight lines that make the haphazard fluidity of the monster and its home feel more anarchic and threatening. It doesn’t belong in this space. Even if it has Daddy’s head.

This review was filed from the world premiere at Fantastic Fest. It debuts on Shudder on October 11th.