The opening sequence of “Closed Circuit,” in which viewers bear witness to London’s bustling Borough Market being decimated by a terrorist bomb at the cost of a couple hundred lives through a collection of overlapping security camera images, is so immediately compelling (even more so for the way that it presents such horrifying imagery in a way that doesn’t feel particularly exploitative) that it sets a fairly high artistic bar pretty early on in the proceedings. The trouble is that not only does the film fail to live up to the enormous promise of those initial moments, it doesn’t even try to do so for the rest of its running time. The result is a dreary and derivative thriller that is nowhere near as smart or controversial as it clearly believes itself to be.

The film is not about the investigation into the bombing; blame is quickly assigned to radicalized Turk Farroukh Erdogan (Denis Moschitto) and a trial is scheduled. The only hiccup is that some of the evidence being introduced by the government is so potentially explosive that not even the defendant himself is allowed to see it for himself. In such cases, defendants like Farroukh are allowed two lawyers—one who will defend him in public and a special advocate who defends him during the closed sessions and is allowed to look at the secret evidence, albeit under orders not to divulge said information to anyone, especially the other lawyer.

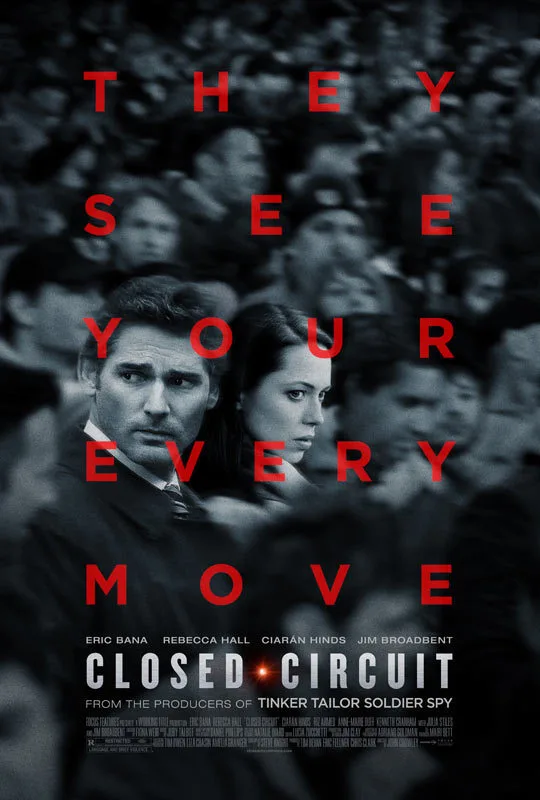

In Farroukh’s case, his public defense will be conducted by Martin Rose (Eric Bana), who snags the gig after his predecessor/mentor commits suicide under suspicious circumstances. In closed court, he will be defended by the ambitious Claudia Simmons-Howe (Rebecca Hall). It turns out that Martin and Claudia once had a brief affair that ended badly, a piece of history that should have forced at least one of them to recuse themselves from the case on ethical grounds. However, neither one wants to give up such a big case and since no one apparently noticed their former romance, they proceed with preparing for their respective trials while effectively setting themselves up for blackmail or worse.

If you have seen a movie—any movie—then you can most likely quickly surmise that nothing about the case is what it seems to be and that just by doing their jobs, both Martin and Claudia are putting themselves in extreme danger at the hands of those who will do anything to prevent their bombshell secrets from being revealed. Rather than go into plot details, I will merely mention that Jim Broadbent plays the seemingly friendly government official, Ciaran Hinds is Martin’s superior, Anne-Marie Duff plays a shadowy figure who will do anything to clean up the mess that she has made and Julia Stiles is a New York Times reporter who is smart enough to piece together a lot of the information but not smart enough to figure out what happens to reporters in movies like this who piece together a lot of the information but lack the security of above-the-title billing.

The ads for “Closed Circuit” make it sound like a smart and—thanks to the material involving closed trials featuring secret evidence and the pros and cons of constant government surveillance of the public—uncommonly topical thriller. The presence of such talents as screenwriter Steven Knight (who wrote the powerful thrillers “Dirty Pretty Things” and “Eastern Promises“), director John Crowley (who previously helmed “Intermission” and “Boy A“) and the top-notch cast would make it seem that it would have to try very hard not to be compelling.

Unfortunately, if there is one thing that the film does excel at, it is at not trying very hard. The screenplay is a shockingly contrived mess that sets up an interesting premise and then has no idea what to do with it other than invoke the same old dramatic cliches in an effort to push the plot along and wrap things up. (This is one of those movies where people just sort of guess the truth behind massive conspiracies with intuition that would make Sherlock Holmes green with envy.) Speaking of the wrap-up, the final act is so nonsensical that anyone who has stuck it out to that point will likely come away from it enraged that their investment paid off so shabbily in the end.

Most disappointingly, even though much of the publicity surrounding the film has tried to connect it with current concerns about privacy versus the need for constant surveillance as a means of protection, the movie itself merely uses the omnipresent closed-circuit cameras as a device and has no other thoughts to offer about them. (Heck, even the current fenderhead fantasy “Getaway” has more thoughts on the subject than this one.) Likewise, the stuff about secret trials fueled by closed evidence sounds both fascinating and potentially enraging but it is tossed off here as just another cheap plot device with all the power of a “Perry Mason” rerun.

There are, of course, worse movies out there right now than “Closed Circuit” but I daresay that few are as disappointing. As I suspect is the case with most viewers, I could certainly use a smart, adult thriller fueled by real-world concerns after a summer of mindless frivolities and the chance to see the perennially underrated Rebecca Hall in a lead role is a welcome bonus in my book. Sadly, both the premise and the cast are wasted on a final product that seems determined to redefine the phrase “humdrum.” Too bad—what a waste of a perfectly good opening shot.