A rest stop for rare individuals. –Motto of the Chelsea Hotel

“Chelsea Walls” is the movie for you, if you have a beaten-up copy of the Compass paperback edition of Kerouac’s On the Road and on page 124 you underlined the words, “The one thing that we yearn for in our living days, that makes us sigh and groan and undergo sweet nauseas of all kinds, is the remembrance of some lost bliss that was probably experienced only in the womb and can only be reproduced (through we hate to admit it) in death.” If you underlined the next five words (“But who wants to die?”), you are too realistic for this movie.

Lacking the paperback, you qualify for the movie if you have ever made a pilgrimage to the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street in New York and given a thought to Dylan Thomas, Thomas Wolfe, Arthur C. Clarke, R. Crumb, Brendan Behan, Gregory Corso, Bob Dylan, or Sid and Nancy, who lived (and in some cases died) there. You also qualify if you have ever visited the Beat Bookshop in Boulder, Colo., if you have ever yearned to point the wheel west and keep driving until you reach the Pacific Coast Highway, or if you have never written the words “somebody named Lawrence Ferlinghetti.” If you are by now thoroughly bewildered by this review, you will be equally bewildered by “Chelsea Walls” and had better stay away from it. Ethan Hawke’s movie evokes the innocent spirit of the Beat Generation 50 years after the fact, and celebrates characters who think it is noble to live in extravagant poverty while creating Art and leading untidy sex lives. These people smoke a lot, drink a lot, abuse many substances, and spend either no time at all or way too much time managing their wardrobes. They live in the Chelsea Hotel because it is cheap and provides a stage for their psychodramas.

Countless stories have been set in the Chelsea. Andy Warhol’s “Chelsea Girls” (1967) was filmed there. Plays have between written about it, including one by Nicole Burdette that inspired this screenplay. Photographers and painters have recorded its seasons. It is our American Left Bank, located at one convenient address. That Hawke would have wanted to direct a movie about it is not surprising; he and his wife, Uma Thurman, who could relax with easy-money stardom, have a way of sneaking off for dodgy avant-garde projects. They starred in Richard Linklater’s “Tape” (2001) about three people in a motel room, and now here is the epic version of the same idea, portraying colorful denizens of the Chelsea in full bloom.

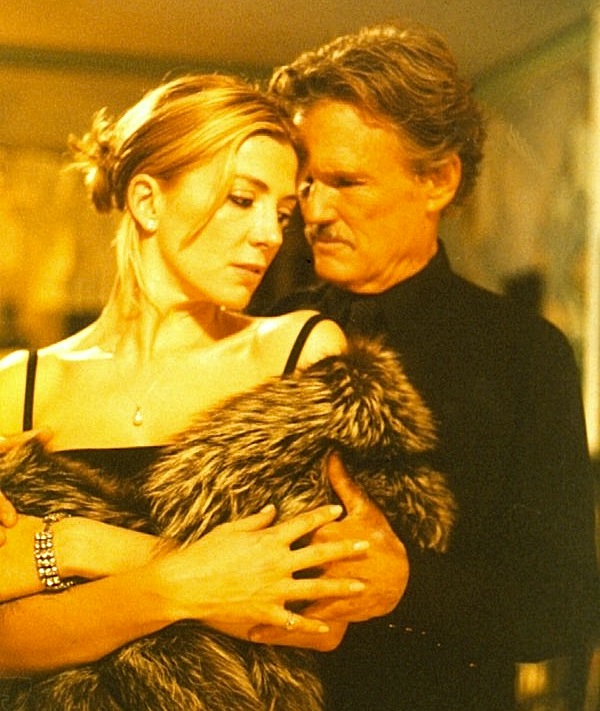

We meet Bud (Kris Kristofferson), a boozy author who uses a typewriter instead of a computer, perhaps because you can’t short it out by spilling a bottle on it. He has a wife named Greta (Tuesday Weld) and a mistress named Mary (Natasha Richardson), and is perhaps able to find room for both of them in his life because neither one can stand to be around him all that long. He tells them both they are his inspiration. When he’s not with the Muse he loves, he loves the Muse he’s with.

Val (Mark Webber) is so young he looks embryonic. He buys lock, stock and barrel into the mythology of bohemia, and lives with Audrey (Rosario Dawson). They are both poets. I do not know how good Audrey’s poems are because Dawson reads them in closeup–just her face filling the screen– I could not focus on the words. I have seen a lot of closeups in my life but never one so simply, guilelessly erotic. Have more beautiful lips ever been photographed? Frank (Vincent D'Onofrio) is a painter who thinks he can talk Grace (Thurman) into being his lover. She is not sure. She prefers a vague, absent lover, never seen, and seems to know she has made the wrong choice but takes a perverse pride in sticking with it. Ross (Steve Zahn) is a singer whose brain seems alarmingly fried. Little Jimmy Scott is Skinny Bones, a down-and-out jazzman. Robert Sean Leonard is Terry, who wants to be a folk singer. The corridors are also occupied by the lame and the brain-damaged; every elevator trip includes a harangue by the house philosopher.

Has time passed these people by? Very likely. Greatness resides in ability, not geography, and it is futile to believe that if Thomas Wolfe wrote Look Homeward, Angel in Room 831, anyone occupying that room is sure to be equally inspired. What the movie’s characters are seeking is not inspiration, anyway, but an audience. They stay in the Chelsea because they are surrounded by others who understand the statements they are making with their lives. In a society where the average college freshman has already targeted his entry-level position in the economy, it’s a little lonely to embrace unemployment and the aura of genius. To actors with a romantic edge, however, it’s very attractive: No wonder Matt Dillon sounds so effortlessly convincing on the audiobook of On the Road .

Hawke shot the film for $100,000 on digital video, in the tradition of Warhol’s fuzzy 16mm photography. Warhol used a split screen, so that while one of his superstars was doing nothing on the left screen, we could watch another of his superstars doing nothing on the right screen. Hawke, working with Burdette’s material, has made a movie that by contrast is action-packed. The characters enjoy playing hooky from life and posing as the inheritors of bohemia. Hawke’s cinematographer, Richard Rutkowski, and his editor, Adriana Pacheco, weave a mosaic out of the images, avoiding the temptation of a simple realistic look: The film is patterned with color, superimposition, strange exposures, poetic transitions, grainy color palettes.

Movies like this do not grab you by the throat. You have to be receptive. The first time I saw “Chelsea Walls,” in a stuffy room late at night at Cannes 2001, I found it slow and pointless. This time, I saw it earlier in the day, fueled by coffee, and I understood that the movie is not about what the characters do, but about what they are. It may be a waste of time to spend your life drinking, fornicating, posing as a genius and living off your friends, but if you’ve got the money, honey, take off the time.