“Chelsea Girls” must be believed to be seen. Like so many other elements of Andy Warhol’s world, it has little intrinsic worth. You must have the faith before you go into the theater; you must be, as the used car dealers say, “pre-sold.” If you aren’t, this film will not win you over on its own terms, as a great film can and should. It will simply lie there before you on the theater wall, winking first with one screen, then the other.

For what we have here is 3 1/2 hours of split-screen improvisation poorly photographed, hardly edited at all, employing perversion and sensation like chili sauce to disguise the aroma of the meal. Warhol has nothing to say and no technique to say it with. He simply wants to make movies, and he does: hours and hours of them. If “Chelsea Girls” had been the work of Joe Schultz of Chicago, even Warhol might have found it merely pathetic.

The key to understanding “Chelsea Girls,” and so many other products of the New York underground, is to realize that it depends upon a cult for its initial acceptance, and upon a great many provincial cult-aspirers for its commercial appeal. Because Warhol has become a social lion and the darling of the fashionable magazines, there are a great many otherwise sensible people in New York who are hesitant to bring their critical taste to bear upon his work. They make allowances for Andy that they wouldn’t make for just anybody, because Andy has his own bag and they don’t understand it but they think they should.

And so Warhol, month by month, looms larger in the press and in the minds of the young people who want to be part of what’s happening, whatever it is. And the really tragic thing is, hundreds and hundreds of hippies and teeny-boppers put on their uniforms and march in to see “Chelsea Girls” and think maybe they enjoyed it, or should have, and to the degree they convince themselves they will have weakened their senses of what makes a film well-made and artistically competent.

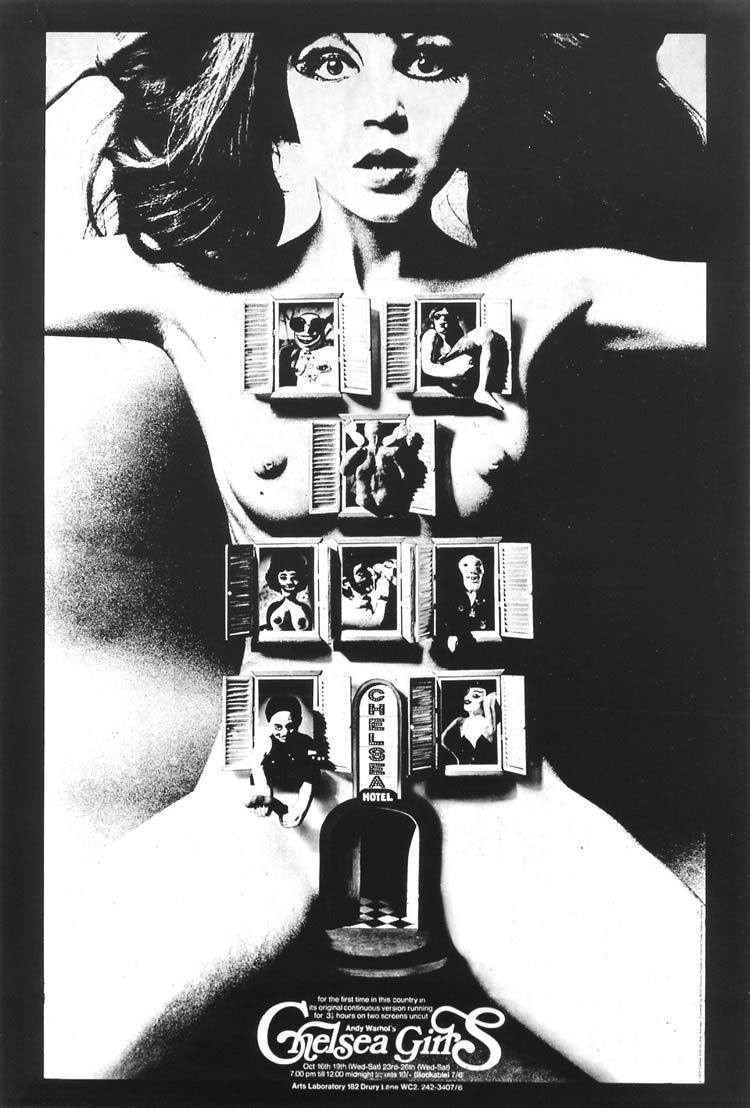

What Warhol has done here, first of all, has been to put all of the appearances of meaning into his film. It’s got to be meaningful because: it has no titles or credits; you can hardly understand the sound track; it has a split screen with two different scenes happening simultaneously; it starts out in black and white and ends up in color; the pictures go in and out of focus incessantly, almost as a reflex action; the film is often overexposed or underexposed; the zoom lens is used to zoom in on insignificant details while significant ones are ignored; all the action is improvised, and a lot of the people in the film are perverted or sado-masochistic or addicted to drugs or like to undress in front of a camera.

When you make a list like this, you realize that Warhol hasn’t missed a trick. With all of those underground gimmicks going for him, his film just has to be deep and profound and, best of all, fashionable. But the funny thing, when you stop to think about it, is that Hollywood has been using the same technique for years and years. How does Hollywood make and advertise a “great” picture? It hires the same old expensive stars, commissions a screenplay exactly like other successful screenplays, copies sure-fire box-office formulas and appeals to the tastes it has identified in its audience. Warhol is doing the same thing on an infinitesimally smaller scale. I don’t even think it’s a put-on. I think he’s serious.

So then you say, OK, he was trying to do something here. So let’s get at it. Let’s take away all the tricks and gimmicks and surface appearances and the ritual camerawork (everybody knows it isn’t a New York underground film unless it’s badly lighted and occasionally out of focus). So what do we have left?

We have one or two pretty good scenes by those rare Warhol actors not raised in the home movie tradition. We have one touching sequence, in which a young man with a Prince Valiant haircut and lots of problems tells us how much people like him, and we know, and he knows we know, they don’t. And beyond these brief good things, what else is there in the 3-1/2 hours that tells us Warhol was informed by an artistic purpose and was attempting a worthy and honest film? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Absolutely nothing at all.