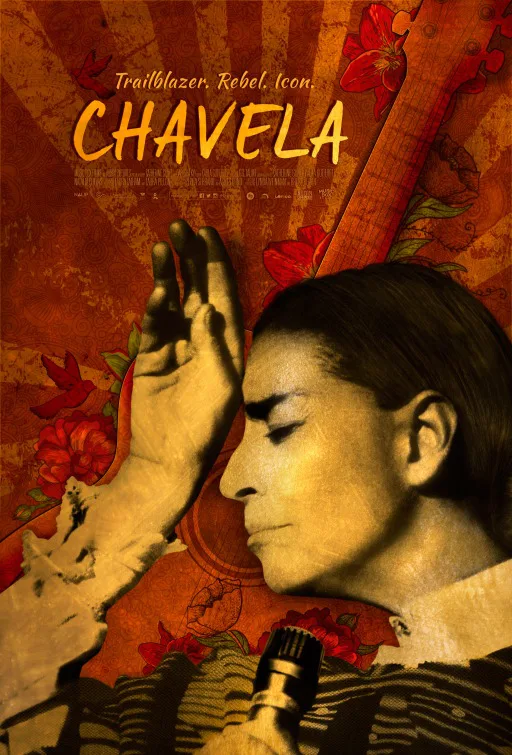

In 1991, filmmaker Catherine Gund sat down with Mexican music icon Chavela Vargas, leading to a candid interview about many parts of her inspirational life. Decades later, Gund (along with co-director Daresha Kyi) has unearthed the footage and tried to create a full, albeit inconsistent documentary starting with the material, as a type of educational tribute to the rebellious lesbian and famous ranchera singer.

As it tells Chavela’s story mostly chronologically aside from that 1991 interview (up until her death in 2012), the fascinating details of her life are touched upon, presenting a legacy that captivated her fans in more ways than one. Gund and Kyi paint a curious image of Chavela’s queer sexuality within a homophobic Mexican art scene, openly resisting the feminine images of a ranchero singer, but forced to be the most macho of anyone in order to be viewed as powerful. In movies, she was portrayed as the ultimate ladykiller, and took on that presence in real life, boasting an androgynous but irresistible presence, while fraternizing with the heaviest of male boozehounds. All of this was before she publicly announced that she was a lesbian, at the age of 81. With a presence that some described as masculine, Chavela’s was a life that vividly proved gender to be a mere social construct, decades before that concept would even be recognized in public discourse. When director Pedro Almodovar is shown in the third act gushing about her work, (which he has featured in his films, in addition to his close friendship with Chavela) it’s but one of example of her trailblazing influence.

Her private life is given a curious examination, and not just in the passage where she talks about her relationship with Frida Kahlo, or people talk about her reputation that Chavela slept with “all of Mexico.” In one striking passage, a lover claims to have been the one who helped her stop drinking, as opposed to Chavela’s initial public claims that it had to do with mysticism. We get a vibrant idea of this intoxicating effect she had on people, but also that of her fascinating desire to be alone. The concept of solitude is a reoccurring lover that people mention, and it completes the poetry about an artist who loved so intensely that she became permanently restless, an island unto herself. It’s the talking head access that seems like the documentary’s biggest addition to her legacy, with people’s accounts continuing her own prowess as being unpredictable. As we get to know her from this movie, she can feel more like the dreams or reflections of the film’s interview subjects than just an ordinary human being.

There’s a strong, necessary focus that the movie has with the somber, delicate sounds of ranchero music, contextualizing Chavela’s placement as someone who changed the game by bringing another level of emotion to it in her performances. A few minutes spent on the songwriter Jose Alfredo Jimenez creates a history of the art form, and also a contrast to what Chavela did when she took Jimenez’s music and turned the ballads of loneliness and longing to mountainous declarations. Footage of Chavela’s full voice crooning her songs, (“as if she were going to die,” someone aptly notes) makes up for roughly a quarter of the documentary’s running time, but you understand how her emotive intensity made these songs linger, and spoke to people beyond words. Lyric text accompanies these videos in the same way “Amy” did with Amy Winehouse’s lyrics, but it has a flat type of effect here. Watching her trembling face and her grasping hands as she sings does not give enough to the story, as much of a powerhouse it represented.

Despite focusing on a definitively interesting artist, “Chavela” nonetheless shares its passion at a languid pace and without her bold artistic values. Eventually the slow zooms into black and white pictures—a common documentary aesthetic, of course—start to take away the filmic rhythm, and the overall impact is lessened. A documentary that starts with a gold mine of personal footage then shows its understandably limited historical resources, but that doesn’t excuse the choice of ugly visual transitions (one fuzzy, non-rendered image slowly fading into another) or the way in which stock footage is used as elementary connective tissue.

Gund and Kyi’s film succeeds as a belated obituary, if to get newcomers to understand her importance, or to provide those familiar with her work a type of celebration across decades. Chavela is presented as a grandiose enigma, the kind that inspires more research afterward and seeking out her music, but the film is too ordinary to feel like it does her legacy complete artistic justice.