In her 1968 review of “Funny Girl,” Pauline Kael wrote that “one of the great pleasures of moviegoing” is “watching incandescent people up there, more intense and dazzling than people we ordinarily encounter in life, and far more charming than the extraordinary people we encounter, because the ones on the screen are objects of pure contemplation.” Joan Crawford stepping into her gorgeously placed key light. Cary Grant entering a room, wearing a grey flannel suit. Marilyn Monroe walking across a room. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers floating around a sound stage. Louise Brooks glancing into the camera, eyes glimmering with mischief. Reveling in beauty is part of the pleasure of film.

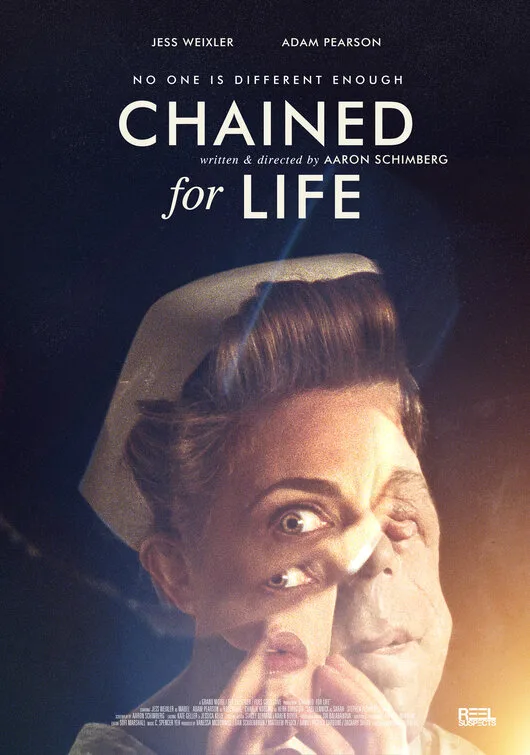

Aaron Schimberg’s “Chained for Life” opens with a lengthy quote from Pauline Kael, similar to her words on “Funny Girl,” about the beauty of actors and actresses. Even without knowing what “Chained for Life” is about, the quote acts as a preemptive finger-wagging, an anticipatory scold, setting us up for all that follows, a meaningful, moving, and often quite funny interrogation of beauty in the movies, and—by extension—how we judge one another (and ourselves) based on looks. This may sound a little bit like a dreary lecture on a well-covered topic, but “Chained for Life”—and Schimberg’s approach—turns the lecture inside out, fracturing it into various “meta” dialogues, before piecing things back together, only now imperfectly, nothing quite fitting together in the same way.

The Kael quote leads us into one of the many show-stopping shots in “Chained for Life” (cinematographer Adam J. Minnick’s work is a stunner throughout): a long take down a hospital hallway, the camera following a woman (Jess Weixler) as she peers into different rooms, finally ending up in an operating room, where a prone patient is being worked on by a doctor and nurse. The mood is gloomy and ominous. When we finally see the woman’s face, her beauty is breathtaking, all ivory skin, golden curls, red lipstick. Because Schimberg has held back a view of her face, the moment is like an old-school movie-star “reveal,” and it works as a counterpoint to the initial Kael quote. There’s something playful and ironic going on, driven home further when an off-screen voice calls “CUT” and there’s another reveal: everything we’ve seen thus far has been a movie in the process of being filmed.

The golden-curled woman is an actress named Mabel (maybe a nod to silent film actress Mabel Normand?), who, when interviewed by a reporter later, gives vaguely “inspirational” answers to the tough questions asked about the potential “exploitive” qualities of the movie she’s acting in. Her character is blind, and Mabel is not blind. How does she justify that? You can imagine how Mabel’s answer—”blindness is a metaphor,” “we all can relate” to “being blind”—would go over on Twitter. Meanwhile, Minnick’s camera floats through the “set,” showing the hustle and bustle of the crew, hearing snippets of overheard conversations (Altman is clearly a guiding inspiration for “Chained for Life”). There are occasional zooms in on this or that person, before the camera moves on like a stalker. The overheard conversations have a random quality, but they twine around the film like vines: electrolysis, “it was an all-female cast,” “It was an all-African-American cast,” circus sideshows, Orson Welles as Othello. A pompous actor (Stephen Plunkett) is heard quoting “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow … ” to the baffled still photographer (Frank Mosley), who murmurs uncomfortably, “Doesn’t ring a bell.” Later, the actor is shown proclaiming to the same still photographer, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” “Who said that?” “I don’t know.”

Through this, a plot emerges. The movie they’re filming is helmed by an autocratic German director (Charlie Korsmo), and rumors swirl that 1.) he is not even German and 2.) he was “raised in a circus.” The pretentious fictional film (“it’s called ‘God’s Mistakes’ in German” someone is overheard saying) is the story of a mad scientist doctor and his evil nurse sidekick operating on their disabled patients, removing their disabilities so they can re-enter society. The cast and crew of “God’s Mistakes” await the arrival of a bus full of people with various physical disabilities, who have been cast in small roles for “authenticity” purposes. When Mabel finally meets her co-star, a man with neurofibromatosis named Rosenthal (played by Adam Pearson, so memorable in Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin“), she is perfectly friendly although she refuses to make eye contact. He admits to her in a forthright manner that he’s having trouble memorizing his lines, and he hopes she can help him. The conversation morphs, and Mabel morphs, too, eventually looking at him dead-on to take him through an impromptu acting lesson. Both actors stare straight at the camera, as Mabel coaches him in the basics of calling up different emotions. At one point, Rosenthal asks her to portray “empathy.” Mabel, skilled at crying to show “sadness” or laughing to show “happiness.” is stumped. Empathy is a tough one.

This is an example of the myriad ways “Chained for Life” works. It makes its points, but it keeps looping back into “meta” territory, the film-within-a-film structure calling to mind Tom DiCillo’s “Living in Oblivion” (one remembers Peter Dinklage’s fictional character’s temper tantrum in “Living in Oblivion” over being hired for “a dream sequence”), Altman’s brutal Hollywood satire “The Player” or Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Beware of a Holy Whore.” There are unmistakable connections, too, with Tod Browning’s still-controversial 1932 film “Freaks,” populated by actual sideshow performers, many of whom had physical disfigurements (Browning, like Herr Director in “Chained for Life”, came from a circus background). The title, “Chained for Life,” has multiple layers, too, a reference to the 1952 exploitation film of the same name, starring the conjoined twin sister-act The Hilton Twins (loosely based on the Hilton’s real-life experiences). Schimberg’s 2009 short film “Late Spring: Regrets for our Youth” detailed an operation to fix his cleft palate, and he has spoken often about his own experiences with being bullied due to what he looked like.

The inexperienced newcomers in the cast of “God’s Mistakes”—a “bearded lady,” a giant, “Siamese twins” (“I thought Siamese twins had been phased out,” murmurs the clueless Mabel), Rosenthal, and others—can’t stay with the rest of the cast and crew because the hotel isn’t accessible, so they sleep in the hospital where they’ve been filming, where patients reside in another wing. Nobody questions this. The newcomers aren’t really a part of the project. At first “Chained for Life” stays with what’s going on in the hotel with the able-bodied, banishing the disabled characters to the background, but Schimberg turns that on its ear.

Every moment contains its opposite, every line has its shadow side (or light side). Schimberg is dazzlingly inventive. There’s a long scene with a cracked mirror, turning a woman’s face into a Picasso, one of Herr Director’s pretentious flourishes. There’s a great scene lampooning bad direction when poor Rosenthal is told (by the director’s off-screen voice) to “step into the light,” and Rosenthal can’t get it right, doesn’t understand the difference between “walking into the light” and “stepping into the light.” The frustrated director says, “It’s like Orson Welles in ‘The Muppet Movie.'” But even this goes beyond a one-note joke. What Rosenthal is being asked to do is “reveal” himself like a monster in a horror movie, or Dracula emerging from the shadows. There’s the scene, and then there’s the commenting on the scene, a balancing act which Schimberg and his amazing cast maintain throughout.

The movie “fakes you out” left and right with cinematic tropes, complicated by backstage dramas, the real-life relationship developing between Mabel and Rosenthal, and the fact that a killer with facial scars is on the loose in the area where they’ve been filming (scars clearly short-hand for evil). “Chained for Life” addresses the issue of representation in film, and how disabled characters and actors are treated, but it goes wider than that into the attitudes, in general, towards those with disabilities, or who don’t conform to some established unfair “norm.” Schimberg’s touch is very light, but the film reaches the depths, not despite his light touch, but because of it.

“Chained for Life” is more than a polemic. There’s a free-floating absurdist mood established, humorous and self-referential, allowing space for the audience to not just feel, but think. This is no small feat.