From his son’s point of view, Edward Bloom’s timing is off. He spent the years before his son’s birth having amazing adventures and meeting unforgettable characters, and the years after the birth, telling his stories to his son, over and over and over again. Albert Finney, who can be the most concise of actors, can also, when required, play a tireless blowhard, and in “Big Fish,” his character repeats the same stories so relentlessly you expect the eyeballs of his listeners to roll up into their foreheads and be replaced by tic-tac-toe diagrams, like in the funnies.

Some, however, find old Edward heroic and charming, and his wife is one of them. Sandra (Jessica Lange) stands watch in the upper bedroom where her husband is leaving life as lugubriously as he lived it. She summons home their son, Will (Billy Crudup). Will, a journalist working in Paris, knows his father’s stories by heart and has one final exasperated request: Could his father now finally tell him the truth? Old Edward harrumphs, shifts some phlegm, and starts recycling again.

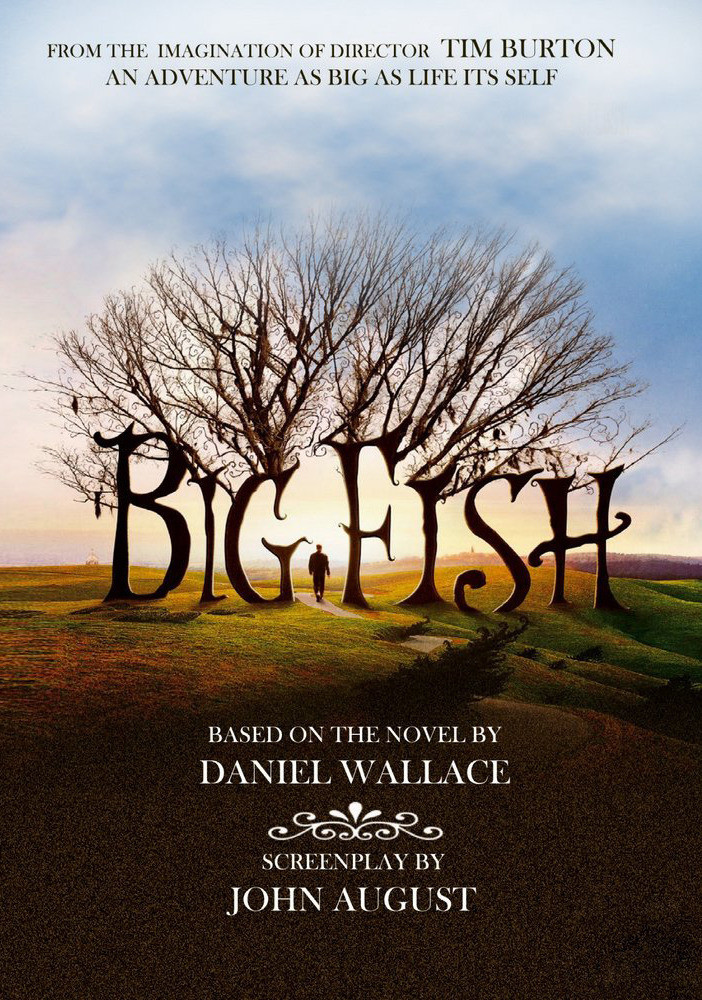

Tim Burton directed the movie, and we sense his eagerness to plunge into the flashbacks, which show Young Edward (Ewan McGregor) and Young Sandra (Alison Lohman) actually having some of the adventures the old man tirelessly recounts. Those memories involve a witch (Helena Bonham-Carter) whose glass eye reflects the way her visitors will die, and a circus run by Amos Calloway (Danny DeVito), where he makes friends with characters such as Karl the Giant (Matthew McGrory).

One day as Edward walks under the Big Top, he becomes mesmerized by his first glimpse of Sandra, and time crawls into slo-mo as he knows immediately this is the woman he is destined to marry.

There are other adventures, one involving a catfish as big as a shark, but it would be hard to top the time he parachutes onto the stage of a Red Army talent show in China, and meets Ping and Jing, a conjoined vocal duo sharing two legs. Now surely all these stories are fevered fantasies, right? You will have to see the movie to be sure, although of course there is also the reliable theory that things are true if you believe them to be so; if it worked for Tinker Bell, maybe it will work for you.

Because Burton is the director, “Big Fish” of course is a great-looking film, with a fantastical visual style that could be called Felliniesque if Burton had not by now earned the right to the adjective Burtonesque. Yet there is no denying that Will has a point: The old man is a blowhard. There is a point at which his stories stop working as entertainment and segue into sadism. As someone who has been known to tell the same jokes more than once, I find it wise to at least tell them quickly; old Edward, on the other hand, seems to be a member of Bob and Ray’s Slow Talkers of America.

There’s another movie opening right now about a dying blowhard who recycles youthful memories while his loved ones gather around his deathbed. His wife summons home their son from Europe. The son is tired of the old man’s stories and just once would like to hear the truth from him. This movie is course is “The Barbarian Invasions” by Denys Arcand, and it is one of the best movies of the year. The two films have the same premise and purpose. They show how, at the end, we depend on the legends of our lives to give them meaning. We have been telling these stories not only to others but to ourselves. There is some truth here.

The difference, apart from the wide variation in tone between Arcand’s human comedy and Burton’s flamboyant ringmastery, is that Arcand uses the past as a way to get to his character, and Burton uses it as a way to get to his special effects. We have the sensation that Burton values old Edward primarily as an entry point into a series of visual fantasies. He is able to show us a remarkable village named Spectre, which has streets paved with grass and may very well be heaven, and has catfish as big as Jumbo, and magicians and tumblers and clowns and haunted houses on and on.

In a sense we are also at the bedside of Burton, who, like Old Edward, has been recycling the same skills over and over again and desperately requires someone to walk in and demand that he get to the point. When Burton gives himself the guidance and anchor of a story, he can be quite remarkable (“Ed Wood,” “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” “Sleepy Hollow“). When he doesn’t, we admire his visual imagination and skillful techniques, but isn’t this doodling of a very high order, while he waits for a purpose to reveal itself?