Dying is not this cheerful, but we need to think it is. “The Barbarian Invasions” is a movie about a man who dies about as pleasantly as it’s possible to imagine; the audience sheds happy tears. The man is a professor named Remy, who has devoted his life to wine, women and left-wing causes, and now faces death by cancer, certain and soon. His wife divorced him years ago because of his womanizing, his son is a millionaire who dislikes him and everything he stands for, many of his old friends are estranged, and the morphine is no longer controlling the pain. By the end of the story, miraculously, he will have gotten away with everything, and be forgiven and beloved.

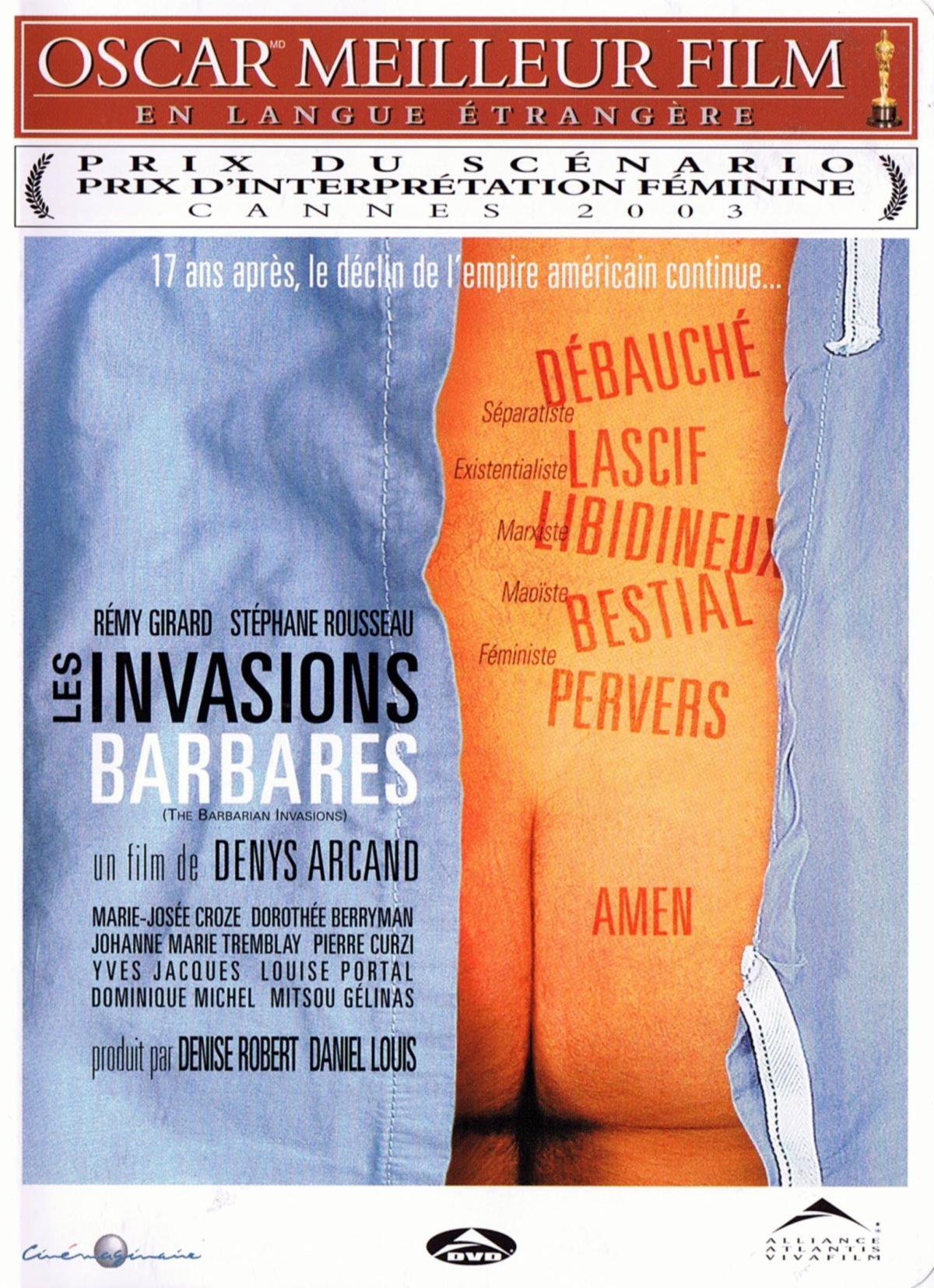

The young embrace the fantasy that they will live forever. The old cling to the equally seductive fantasy that they will die a happy death. This is a fantasy for adults. It is also a movie with brains, indignation, irony and idealism — a film about people who think seriously, and express themselves with passion. It comes from Denys Arcand of Quebec, whose “The Decline of the American Empire” (1986) involved many of the same characters during the fullness of their lives. At that time they either worked in the history department of a Montreal university or slept with somebody who did, and my review noted that “everybody talks about sex, but the real subject is wit … their real passion comes in the area of verbal competition.”

When people are building their careers, they need to prove they’re better than their contemporaries. Those who win must then prove — to themselves — that they’re as good as they used to be. Whether Remy was a good history professor is an interesting point (his son has to bribe three students to visit his bedside, but one of them later refuses to take the money). He certainly excelled in his lifestyle, as the lustiest and most Falstaffian of his circle, but every new conquest meant leaving someone behind — and now, at the end, he seems to have left almost everyone behind.

We’ve all known someone like Remy. Frequently their children don’t love them as much as their friends do. We have a stake in their passions; they live at full tilt so we don’t have to, and sometimes even their castaways come to admire the life force that drives them on to new conquests, more wine, later nights. His former wife Louise (Dorothee Berryman) calls their son Sebastien (Stephane Rousseau) in London, where he is a rich trader, to tell him his father is near death, and although he hasn’t spoken to the old man in a long time, Sebastien flies home with his fiancee Gaelle (Marina Hands).

Their first meeting goes badly; it is a replay of Remy’s socialist rejection of Sebastien’s values and his “worthless” job. But Sebastien has learned from the financial world how to get things done, and soon he has bribed a union official to prepare a private room for his father on a floor of the hospital no longer in use. He even wants to fly his father to America for treatment, but Remy blusters that he fought for socialized medicine and he will stick with it. The movie is an indictment of overcrowded Canadian hospitals and absent-minded care-givers, but it also reveals a certain flexibility, as when the nun caring for Remy tells his son that morphine no longer kills the pain … but heroin would.

How Sebastian responds to that information leads to one of the movie’s most delightful sequences, and to the introduction of a drug addict named Nathalie (Marie-Josee Croze), who becomes another of Remy’s caregivers. Nathalie’s story and her own problems are so involving that Croze won the best actress award at Cannes 2003.

Sebastien calls up his father’s old friends. Some are Remy’s former lovers. Two are gay. One, Remy’s age, has started a new family. They gather at first rather gingerly around the deathbed of this person they had drifted away from, but eventually their reunion becomes a way to remember their younger days, their idealism, their defiant politics. Remy is sometimes gray and shaking with pain, but the movie sidesteps the horrendous side-effects of chemotherapy and uses heroin as the reason why he can play the graceful and even ebullient host at his own passing. There is a scene at a lakeside cottage that is so perfect and moving that only a churl would wonder how wise it is to leave a terminally ill man outside all night during the Quebec autumn, even with blankets wrapped around him.

“The Barbarian Invasions,” also written by Arcand, is manipulative without apology, and we want it to be. There’s no market for a movie about a man dying a miserable death, wracked by the nausea of chemo. Indeed Remy is even allowed his taste for good wines and family feasts. And what a marvel the way his wife and his former (and current!) lovers gather around to celebrate what seems to have been the most remarkable case of priapism any of them have ever encountered. They are not so much forgiving him, I think, as envying his ability to live on his own terms and get away with it. His illusions are all he has, and although they were deceived by them, they don’t want Remy to die without them. As a good friend of mine once observed, nobody on his deathbed ever says, “I’m glad I always flew economy class.”