Justin Lin‘s “Better Luck Tomorrow” has a hero named Benjamin but depicts a chilling hidden side of suburban affluence that was unseen in “The Graduate.” Its heroes need no career advice; they’re on the fast track to Ivy League schools and well-paying jobs, and their straight-A grades are joined on their resumes by an improbable array of extracurricular credits: Ben lists the basketball team, the Academic Decathlon team and the food drive.

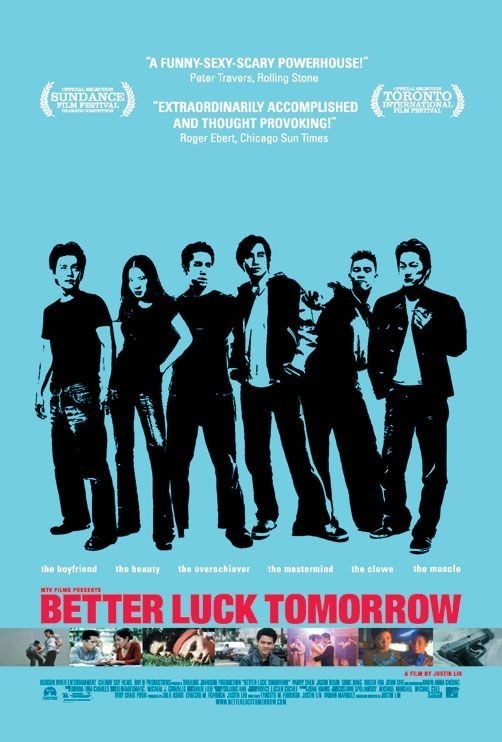

What he doesn’t mention is the thriving business he and his friends have in selling cheat sheets. Or their drug sideline. Or the box hidden in his bedroom and filled with cash. Ben belongs to a group of overachieving Asian-American students in a wealthy Orange County suburb; they conform to the popular image of smart, well-behaved Asian kids, but although they have ambition they lack values, and step by step they move more deeply into crime. How deep is suggested by the film’s opening scene, where Ben (Parry Shen) and his best friend, Virgil (Jason Tobin), are interrupted while sunbathing by the sound of a cell phone ringing on a body they have buried in Virgil’s backyard.

“Better Luck Tomorrow” is a disturbing and skillfully told parable about growing up in today’s America. These kids use money as a marker of success, are profoundly amoral, and project a wholesome, civic-minded attitude. They’re on the right path to take jobs with the Enrons of tomorrow, in the dominant culture of corporate greed. Lin focuses on an ethnic group that is routinely praised for its industriousness, which deepens the irony, and also perhaps reveals a certain anger at the way white America patronizingly smiles on its successful Asian-American citizens.

Ben, Virgil and their friends know how to use their ethnic identity to play both sides of the street in high school. “Our straight A’s were our passports to freedom,” Ben says in his narration. No parents are ever seen in the movie (there are very few adults, mostly played by white actors in roles reserved in most movies for minority groups). The kids get good grades and their parents assume they are studying, while they stay out late and get into very serious trouble.

“Better Luck Tomorrow” has all the obligatory elements of the conventional high school picture. Ben has a crush on the pretty cheerleader Stephanie Vandergosh (Karin Anna Cheung), but she dates Steve (John Cho), who plays the inevitable older teenager with a motorcycle and an attitude. Virgil is unlucky with girls, but thinks he once spotted Stephanie in a porno film (unlikely, but gee, it kinda looks like her). Han (Sung Kang) comes up with the scheme to sell homework for cash, and Daric (Roger Fan) is the overachiever who has, no doubt, the longest entry under his photo in the school yearbook.

These students never refer to, or are identified by, specific ethnic origin; they’re known as the “Chinese Mafia” at school because of their low-key criminal activities, but that’s not a name they give themselves. They may be Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, but their generation no longer obsesses with the nation before the hyphen; they are Orange County Americans, through and through, and although Stephanie’s last name and Caucasian little brother indicate she was adopted, she brushes aside Ben’s tentative question about her “real parents” by saying, “These are my real parents.” “Better Luck Tomorrow” is a coming-of-age film for Asian Americans in American cinema. Like African-American films that take race for granted and get on with the characters and the story, Lin is making a movie where race is not the point but simply the given. After Ben joins the basketball team, a writer for the high school paper suggests he is the “token Asian” bench-warmer, and when students form a cheering section for him, he quits the team in disgust. He is not a token anything (and privately knows he has beaten the NBA record for free throws).

The story is insidious in the way it moves stealthily into darker waters while maintaining the surface of a high school comedy. There are jokes and the usual romantic breakthroughs and reversals, and the progress of their criminal career seems unplanned and offhand, until it turns dangerous. I will not reveal the names of the key characters in the climactic scene, but note carefully what happens in terms of the story; perhaps the film is revealing that a bland exterior can hide seething resentment.

Justin Lin, who directed, co-wrote and co-produced, here reveals himself as a skilled and sure director, a rising star. His film looks as glossy and expensive as a megamillion studio production, and the fact that its budget was limited means that his cinematographer, Patrice Lucien Cochet; his art director, Yoo Jung Han, and the other members of his crew were very able and resourceful. It’s one thing to get an expensive look with money and another thing to get it with talent.

Lin keeps a sure hand on tricky material; he has obvious confidence about where he wants to go and how he wants to get there. His film is uncompromising and doesn’t chicken out with a U-turn ending. His actors expand and breathe as if they’re captives just released from lesser roles (the audition reel of one actor, Lin recalls, showed him delivering pizzas in one movie after another). Parry Shen gives a watchful and wary undertone to his all-American boy, and Karin Anna Cheung finds the right note to deal with a boy she likes but finds a little too-goody. “Better Luck Tomorrow” is not just a thriller, not just a social commentary, not just a comedy or a romance, but all of those in a clearly seen, brilliantly made film.