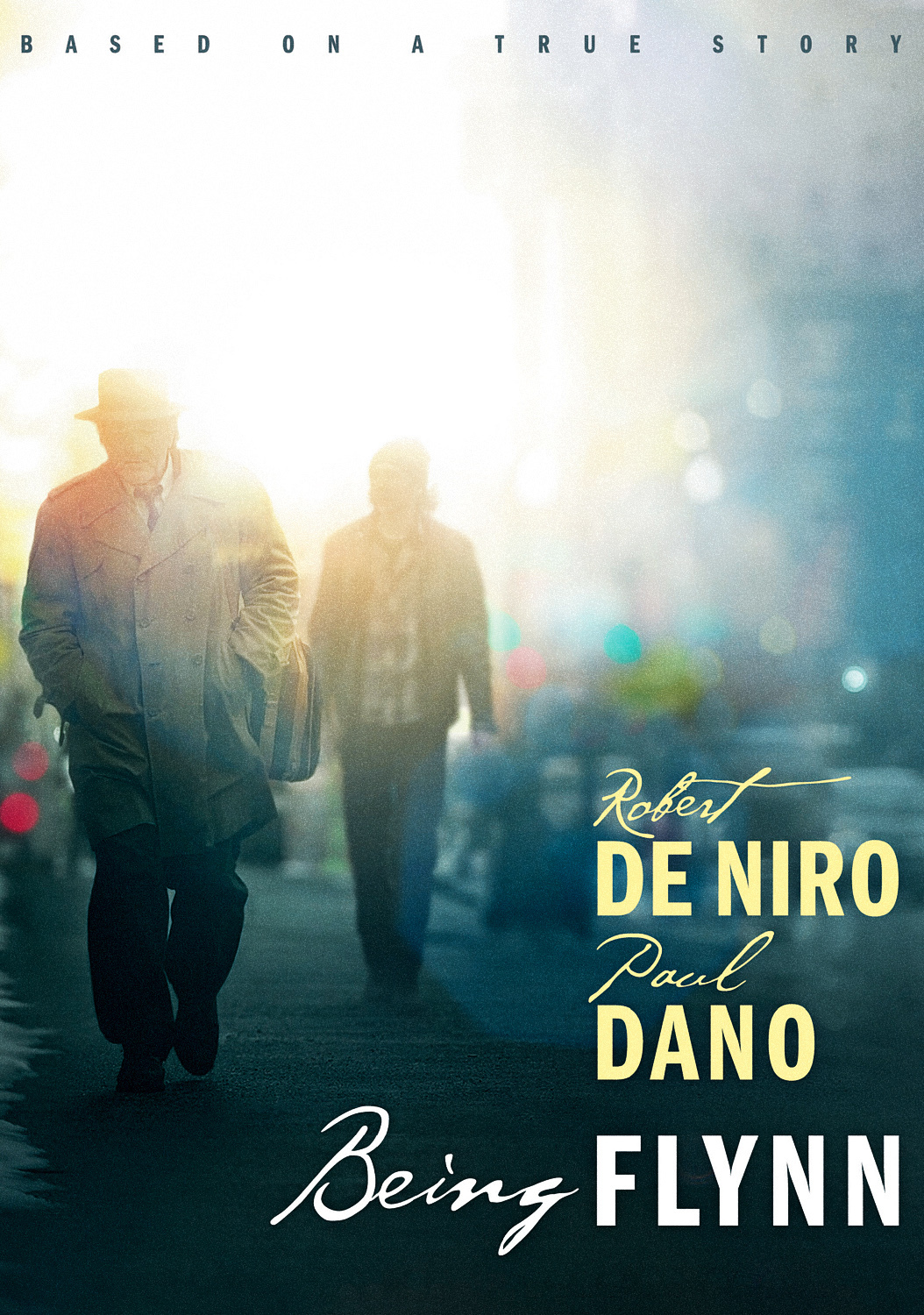

An early shot in “Being Flynn” shows Robert De Niro behind the wheel of a Yellow Cab, and the ground shifts beneath the movie. To summon up his most iconic role must represent De Niro’s faith in this film. I can understand why he felt that much faith in the project, but I’m not sure the film deserves it.

De Niro plays Jonathan Flynn, in his own estimation one of the three greatest American writers (the others: Mark Twain and J.D. Salinger). He claims publishers have been bidding fortunes on his work in progress, but we follow his decline: He loses his apartment, loses his cab and is reduced to hanging out in the well-heated lobbies of buildings.

We learn about him from his son, Nick Flynn (Paul Dano), who also intends to be a great writer; there are two voiceovers in the film, one by Jonathan, one by Nick, although Nick may be writing his father’s narration. There is a real Nick Flynn, who first told this story in a 2005 memoir, Another Bull**** Night in Suck City (asterisks mine). Whether his real-life father was a writer I’ve been unable to determine, but we know his parents were divorced when he was young, his mother killed herself when he was 22, and he actually did go to work in a homeless shelter, where he met his father for the first time when the old man turned up looking for a room for the night.

If you want to be a writer and something like that happens to you, it’s inevitable that it will turn up in a book. By all accounts, the memoir is a powerful piece of work. Throughout the film, Nick’s subtext is: Am I doomed to be a failure like my dad? Nick tells us his father was mostly absent during his childhood — in prison for bad check writing. His mother (Julianne Moore) explains this to the boy as well as she can. Alcohol is the problem of the father, cocaine becomes the problem of the son. Assuming such a life doesn’t kill you, it reads nicely in those little authors’ biographies on the insides of dust jackets: The author overcame drug addiction and worked in a homeless shelter before winning a Guggenheim.

What’s admirable about “Being Flynn” is that it doesn’t cave in to the standard Hollywood redemption formulas, with the father redeemed and the son inspired. It’s more complicated than that. Jonathan Flynn perhaps has mental problems or simply likes to prevaricate; does he really believe in his greatness? As for the son, his childhood memories seem limited to repeated games of catch and rummaging through a box full of letters that Jonathan sent from prison. Julianne Moore plays a loving mother, but not much is done with the character.

Paul Dano is an actor who can be distant and mystifying. He makes it interesting. He sometimes approaches a scene with passive aggression. He understands the material, he understands the character, but he isn’t going to do the heavy lifting for us. In films like “There Will Be Blood,” “The Ballad of Jack and Rose” and “Meek's Cutoff,” he plays the silent dissenter to the dominant characters.

In “Being Flynn,” Nick uses his writing to express feelings he isn’t forthright about in life. When Jonathan unexpectedly materializes, he’s at a loss, and his feelings are the subject of the film. De Niro’s father is a man who has run out of options. There is no longer anyone who much cares if he’s telling the truth. Nick, however, has a girlfriend named Denise (Olivia Thirlby) who cares for him and sees that he needs to be doing something. She works at the homeless shelter and persuades him to give it a try. She perhaps instinctively spots Nick as one of those “writers” for whom it’s hard work, not writing every day.

I’m happy that the film didn’t settle for the Hollywood redemption formula, but ambivalent that it leaves us in suspension. Neither character is ready to have his chance meeting result in anything definite. Jonathan seems doomed. That would be the film’s easy way out, but it isn’t sure which way it should take. In a sense, director Paul Weitz (“About a Boy“) has the same kind of passivity that works for Dano: He’ll take us so far and leave us.

Robert De Niro has been through a bad patch lately. His contemporary Al Pacino has moved from one success to another by going out of his way to choose challenging projects (“You Don’t Know Jack,” “The Merchant of Venice“). De Niro, perhaps absorbed in his Tribeca enterprises, has seemed to drift. He and Weitz worked together on “Little Fockers,” not a high point for either one. Now here is a much more ambitious film that almost but not quite justifies the hope inspired by that shot of a Yellow Cab.

Note: The incomparable Lili Taylor, seen in the homeless shelter, is Nick Flynn’s real-life companion.