The first five minutes of Halina Rejn’s “Babygirl” tell you everything you need to know about Romy (Nicole Kidman), or at least everything relevant to her ensuing erotic adventure. Romy and her husband Jacob (Antonio Banderas) have sex, and it appears to be a mutually ecstatic experience. She then sneaks down the hallway to watch porn in the bathroom, finishing herself off in secret. This appears, on the surface, to be familiar erotic thriller territory, where unruly sexual impulses threaten to topple a “perfect” marriage (even though we’ve literally just seen that it is not perfect). Because “Babygirl” opens this way, we do not have to suffer through interminable scenes where Romy and Jacob are presented as a perfect couple, busy with work and children, unaware of the danger inside the perimeter of the proverbial white picket fence. “Babygirl” is savvier than that. It’s also funnier than that. Reijn is going after something a little bit deeper than “woman’s happy homelife destroyed by her uncontrollable sexual desires.”

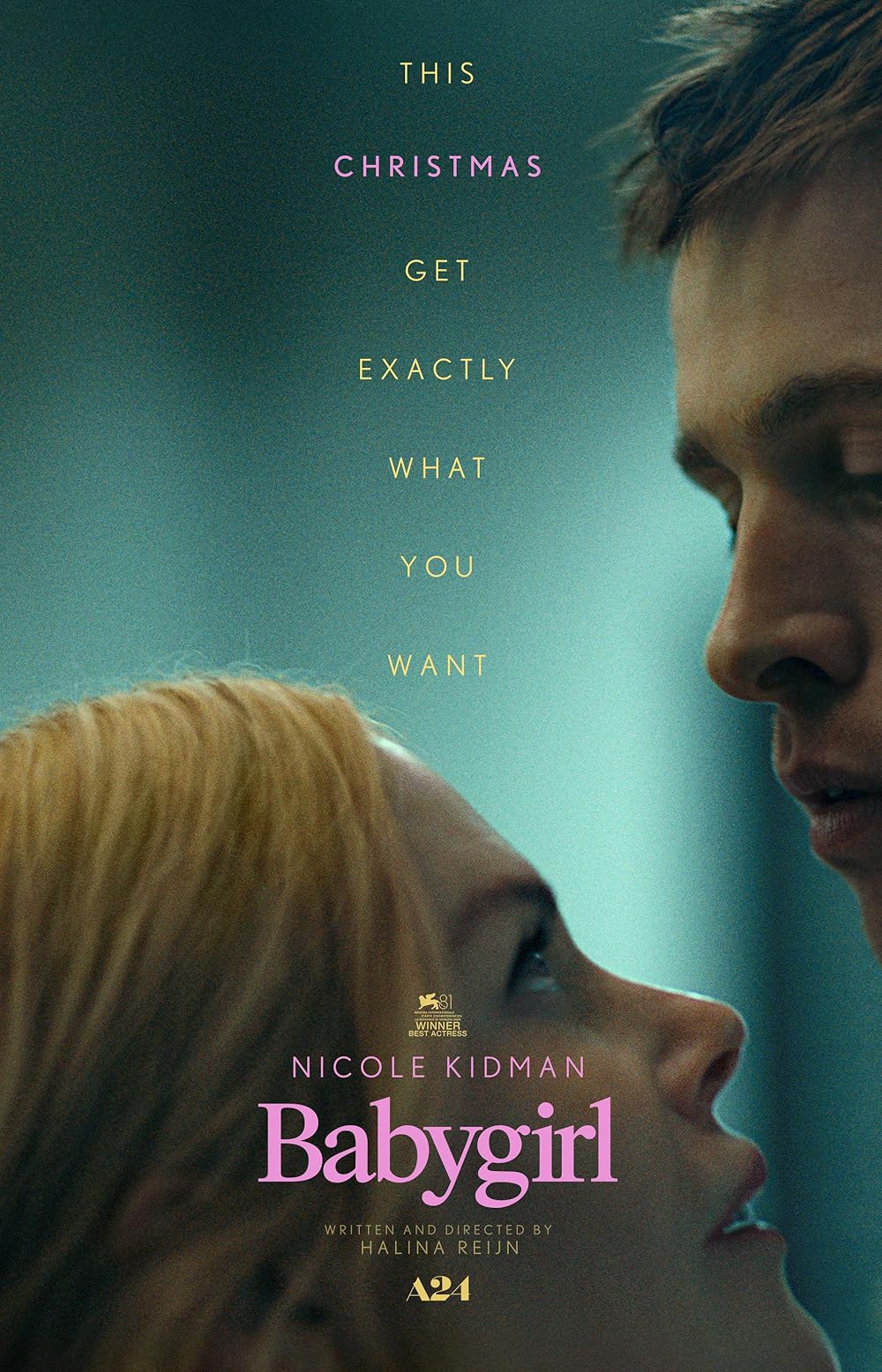

Romy is the founder and CEO of a company that develops robotics for warehouse delivery systems, removing the need for humans. Jacob is a theatre director rehearsing a production of Hedda Gabler, which is not coincidentally a urtext for women trapped in unhappy marriages. When characters have metaphor-heavy jobs, you know there’s trouble in paradise. “Babygirl” wastes no time. Romy first sees Samuel (Harris Dickinson) on a crowded city sidewalk, taking control of an off-leash dog. She is riveted by his calm, firm gestures. Later that day, he is part of the cluster of interns brought into her office. He looks at her with a disturbing lack of subservience. He looks at her like he’s an equal. His presence and his attitude throw her off.

In their initial one-on-one interaction, Samuel tosses out the observation that he thinks she likes to be told what to do. The moment is shocking. His comment is so inappropriate it knocks the wind out of her. He senses the truth she’s been hiding and goes right for it, speaks right to it. He’s not manipulative. He’s straightforward. This is such unexpected behavior from an intern she can’t gather up a defense. Besides, she’s into it, and he knows it. Soon, she’s addicted to this thing with Samuel, all while being at war with her impulses. She doesn’t understand sex as a game involving explicitly stated consent. It’s totally foreign to her. Samuel has to explain the concept of consent to her. And let me tell you, his definition is better than Christian Grey’s. Samuel gets it.

Marlene Dietrich once observed, “In America, sex is an obsession. In other parts of the world it’s a fact.” This explains a lot about America’s schizophrenic relationship to sex, and how this is reflected in American cinema. Our current cinematic moment is bafflingly sexless, which inhibits all kinds of genres, not just erotic ones. Juvenile sex humor is sometimes allowed. “Fifty Shades of Grey” was deceptive. Yes, there was kinky sex, but it was “legitimized” by a wedding ceremony, showing a puritanical need to put a container around “dark sexual impulses.” The absence of sex is evidence of the obsession with it. If sex is just a “fact,” however, then it doesn’t have the same threatening power. In “Babygirl,” both “obsession” and “fact” are in operation. To Romy, sex is an obsession. To Samuel, sex is a fact.

This year’s “The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed,” written and directed by Joanna Arnow (who also stars) is about a “submissive” woman, and it shows how it’s really tough to find a dom who is not also a psycho, or just a jerk pretending to be a dom. The tone of Arnow’s film is extreme deadpan, whereas “Babygirl”‘s tone is that of a comic-opera, but the frankness with which these things are discussed in both films is a breath of fresh air.

Kidman plays Romy at a fever pitch, and she is very effective. But Harris Dickinson is the real star here. If Samuel wasn’t portrayed in the exact right way, the whole delicate thing would fall apart. The performance is not really a “revelation” because Dickinson has been distinguishing himself from the moment he arrived back in 2017 in Eliza Hittman’s “Beach Rats” (2017). In Steve McLean’s “Postcards from London,” Dickinson showed his willingness to appear in experimental material and, most importantly, to be objectified by the camera (and others). He was the “object of desire” in that film, as well as in Xavier Dolan’s “Matthias and Maxime,” where his aggressively hetero behavior hinted at protesting too much. With “Triangle of Sadness,” he played a male model, leaning into what was already obvious. In all films, he brought to the table a calm sense of being aware of what he looks like, aware people are looking at him, and he is fine with allowing it. This is a very rare quality in male actors. Richard Gere had it. In “Scrapper,” one of my favorite films of 2023, Dickinson played a young guy who abandoned his daughter at birth and returned when she was 12. Even though you could judge the character, he was such an open-faced, big, goofy guy it was hard to be mad at him. Dickinson has reached another exciting level with “Babygirl.”

We get only a few glimpses of Romy’s childhood. She grew up in what she calls a “commune cult,” and does EMDR therapy a couple of times a week. Trauma is implied but not explained. Since this element is barely developed, it felt unnecessary and didn’t really add to any understanding of Romy’s motivations. To repeat, everything you need to know about Romy happens in the first five minutes.

Cristobal Tapia de Veer’s original score is symphonic and often gigantic, creating a portentous mood, which somehow manages to avoid self-seriousness. The needle drops are memorable, particularly the use of INXS’ “Never Tear Us Apart” and the scene where a shirtless post-coital Samuel, holding a glass of Scotch, dances around the posh hotel room to George Michael’s “Father Figure,” his movements slow and languid, aware he’s on display, dancing to please himself, and knowing he’s pleasing to her. The moment is mesmerizing.

“Babygirl” is a high-wire act. It’s a small miracle the film works as well as it does.