“Postcards from London,” directed by Steve McLean, has a lot of interesting ideas in it. It’s a survey course in Art History, as filtered through the perspectives of five art-mad male escorts. McLean, a multi-media artist, whose only other feature was 1994’s “Postcards from America,” an adaptation of the memoirs of AIDS activist/filmmaker/performer David Wojnarowicz, creates a swoony romantic vibe in “Postcards from London,” using frankly artificial sets to suggest the underworld of London’s hustler scene. The film is best when it doesn’t take itself too seriously. Unfortunately, for the most part it takes itself very seriously.

“Postcards from London” shows the journey of Jim (Harris Dickinson), a naive boy from Essex who travels to London looking for “mystery and possibility,” as he tells his uncomprehending parents. Once in the big city, he is taken under the collective wing of four adorable male escorts (Jonah Hauer-King, Alessandro Cimadamore, Leonardo Salerni, and Raphael Desprez), who train him in their profession. They call themselves “raconteurs,” telling Jim that post-coital conversation is the real commodity: “In a society as atomized as ours, people crave intimacy. And that’s the service we provide.” Wide-eyed Jim commits to his course of study, reading books about painting and sculpture, until he’s ready to start entertaining clients.

But there’s a problem. When Jim stares at a great work of art, he goes into spasms of awe and then faints. Upon awakening, he finds himself actually in the painting which caused the convulsion. (These sequences, where McLean has his cast re-create great works of Caravaggio and Titian, etc., against a velvety-black background, are the best in the film.) The raconteurs take Jim to an eccentric doctor who diagnoses him with the rare condition known as Stendhal Syndrome. (Stendhal Syndrome is not just the title of a horror movie directed by Dario Argento, it is an actual thing, named after the 19th-century author who described vividly his experience visiting the Basilica of Saint Croce: “I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call ‘nerves’. Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.”) Jim is devastated at the diagnosis: how can one be a raconteur if one can’t even look at art without swooning?

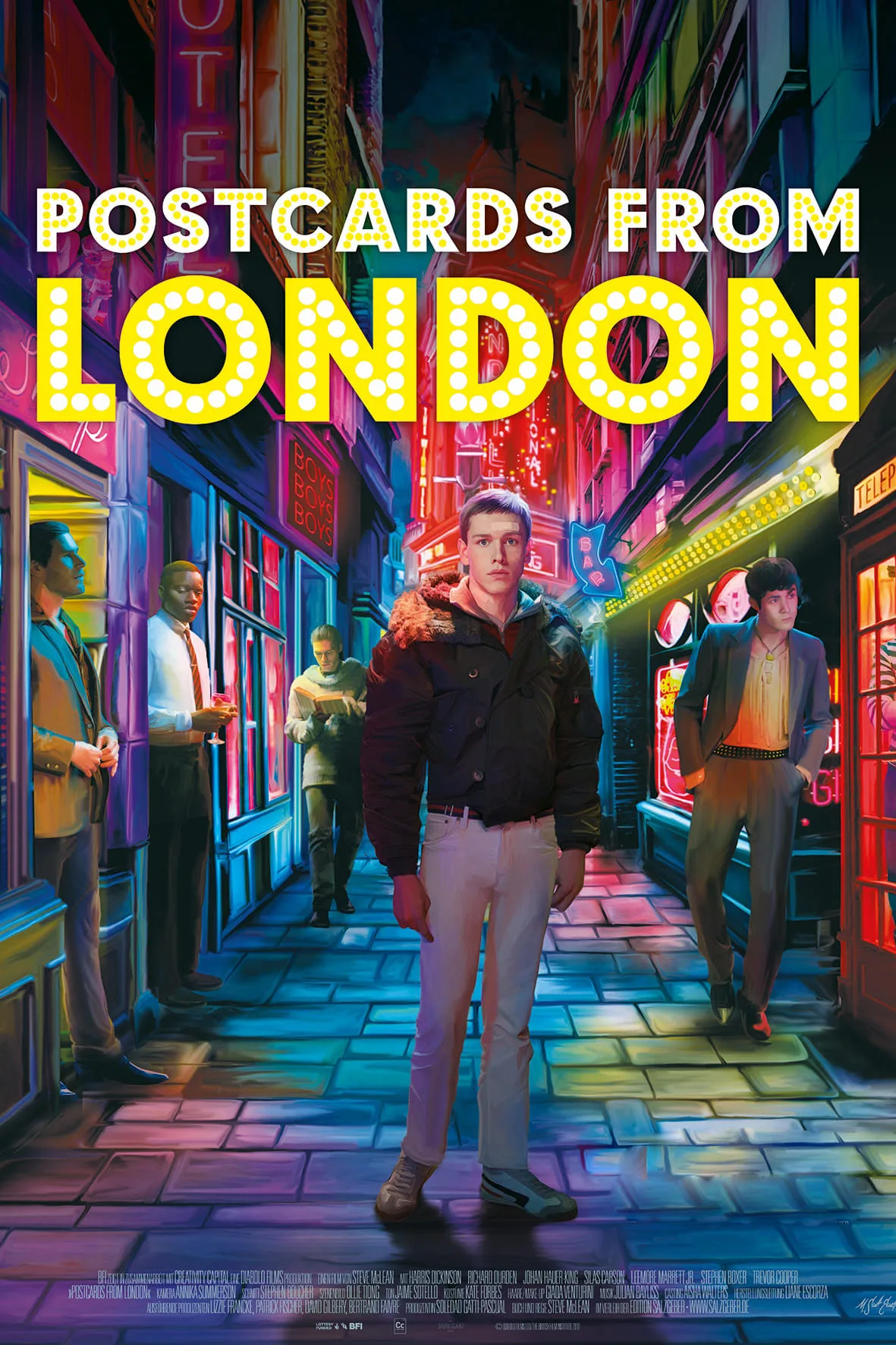

If this all sounds a little precious, that’s because it is. References fly around the screen too fast to even count, tributes to Pasolini, Oscar Wilde, Guido Reni, Francis Bacon. Godard’s “Band of Outsiders” gets a nod. The guiding star of the film is Caravaggio, who comes to life at one point (played by Ben Cura), challenging his muse to a duel. Ollie Tiong’s production design highlights the artificiality of the project. Nothing was filmed out in the real world; it all appears to take place on carefully constructed sets, a theatricalized version of London’s underworld, its alleys and bars, cheap motel rooms, rooftops bathed in neon. Inserts of neon signs are used as transitions, so often they feel like awkward placeholders. What engages McLean is ideas, but “Postcards from London” belabors the point almost to distraction (it may have worked better as a short film).

Harris Dickinson, a newcomer, first got attention for his portrayal of the closeted Brooklyn jock in Eliza Hittman’s 2017 film “Beach Rats.” Dickinson has a pale beautiful face, a semi-blank quality, and the sculpted body of a Greek God. This combination made him captivating in “Beach Rats,” which was a tactile exploration of the erotic possibilities of male bodies, the sexual energy inherent in all that tension. Dickinson’s surface was a smokescreen, a camouflage, and the same thing happens in “Postcards from London,” although here, subtext is obliterated. Hittman’s film was all subtext, and Dickinson’s particular qualities flourished in that wordless space. Here, it’s all text. Everyone talks about Jim’s beauty obsessively and he accepts the attention with equanimity. “Postcards from London” is not meant to be a psychological study, and it’s not meant to be realistic. But since Jim comes across as a wide-eyed nonentity (no fault of Dickinson’s: he plays the role as written), it’s hard to know what to think of his intellectual and artistic journey.

The film is pretty coy about sex. This may be part of the point, but it creates a semi-arch mood, tough to take in large doses. One needs only to compare “Postcards from London” to the fever-dream of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Querelle,” adapted from Jean Genet’s novel, to sense some of the problems in McLean’s approach. “Postcards from London” wears its influences on its sleeve, and it has “Querelle” written all over it. Fassbinder is name-checked in the film, as is Genet, and there are a couple of scenes in a bar reminiscent of Querelle’s entire seedy-glamorous aesthetic, where stylized sailors in white sailor hats pose around a pool table. “Postcards from London” lacks the subversive charge of Fassbinder, not to mention Genet, or any of the other artists mentioned, whose works came out of a potent blend of sex, beauty, suffering and criminality.

Every artist has to struggle to wrest his or her own work free from the influence of other artists. American poet Hart Crane did not feel free to start his own work until he had tackled T.S. Eliot, whose influence was so gigantic it silenced him (Crane confessed to poet Allen Tate, “You see it is such a fearful temptation to imitate him that at times I have been almost distracted.”) Oscar Wilde, as a student at Oxford, wrote provocative papers about the men who helped form his tastes—Walter Pater, Algernon Swinburne – before he emerged, eventually, as his own brilliant creation. Oscar Wilde served the same function for many of his contemporaries, who were so bowled over by him they feared the obliteration of their own work. (After meeting Oscar Wilde in Paris, André Gide apologized to Paul Valéry for being out of touch: “Forgive my being silent: After Wilde, I only exist a little.”)

Something like this is going on in “Postcards from London.” It’s a personal film about the artists who matter to McLean (the end credits includes a long list of painters and their works). His attempt to break free from the hold these artists have over his imagination is a work in progress, as evidenced by “Postcards,” but there’s still a lot here that’s thought-provoking.