The Oliver Sacks case study that inspired “At First Sight” tells the story of a man who has grown accustomed to blindness, and then is offered an operation that will restore sight. The moment when the bandages are removed all but cries out to be filmed. But to have sight suddenly thrust upon you can be a dismaying experience. Babies take months or years to develop mind-eye-hand coordination; here is an adult blind person expected to unlearn everything he knows and learn it again, differently.

The most striking moment in “At First Sight” is when the hero is able to see for the first time since he was 3. “This isn’t right,” he says, frightened by the rush of images. “There’s something wrong. This can’t be seeing!” And then, desperately, “Give me something in my hands,” so that he can associate a familiar touch with an unfamiliar sight.

If the movie had trusted the fascination of this scene, it might have really gone somewhere. Unfortunately, its moments of fascination and its good performances are mired in the morass of romance and melodrama that surrounds it. A blind man can see, and still he’s trapped in a formulaic studio plot.

The buried inspiration for this film, I suspect, is not so much the article by Oliver Sacks as “Awakenings” (1990), a much better movie based on another report by Sacks. Both films have similar arcs: A handicapped person is freed of the condition that traps him, is able to live a more normal life for a time, and then faces the possibility that the bars will slam shut again. “Charly” (1968), about a retarded man who gains and then loses super intelligence, is the classic prototype.

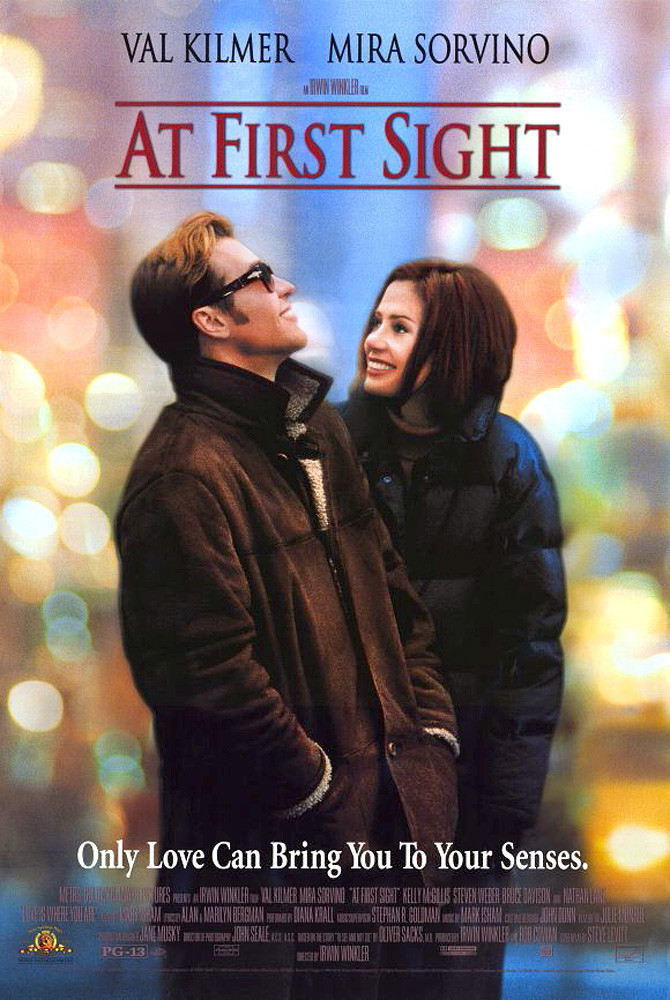

In “Awakenings,” Robert De Niro plays a man locked inside a rare form of sleeping sickness. Under treatment by a brilliant doctor (Robin Williams), the disease goes into remission, and the man, who had not been able to speak or move for years, regains normal abilities. He even falls a little in love. Then the regression begins. In “At First Sight,” Val Kilmer plays Virgil, a blind man who meets and falls in love with a woman (Mira Sorvino). She steers him to a doctor (Bruce Davison) whose surgical techniques may be able to restore his sight.

The woman, Amy, is a New York architect. She’s left an unhappy relationship: “For the last five years I have lived with a man with the emotional content of a soap dish.” She goes to a resort town on vacation and sees a man skating all by himself on a forest pond. Later, she hires a massage therapist, who turns out to be the same person, a blind man named Virgil (Kilmer). The moment he touches her, she knows he is not a soap dish. She cries as the tension drains from her.

Virgil knows his way everywhere in town, knows how many steps to take, is friendly with everybody. He is protected by a possessive older sister named Jennie (Kelly McGillis), who sees Amy as a threat: “We’re very happy here, Amy. Virgil has everything he needs.” But Amy and Virgil take walks, and talk, and make love, and soon Virgil wants to move to New York City, where Amy knows a doctor who may be able to reverse his condition.

The movie is best when it pays close attention to the details of blindness and realities of the relationship. When the two of them take shelter from the rain, he is able to sense the space around him by the sound of the rain outside. His dialogue is sweetly ironic; when they meet for a second time, he says, “I was describing you to my dog, and how well you smelled.” All of this is just right, and Kilmer and Sorvino establish a convincing, intimate rapport–a private world in which they communicate easily. But the conventions of studio movies require false melodrama to be injected at every possible juncture, and so the movie manufactures a phony and unconvincing breakup, and throws in Virgil’s long-lost father, whose presence is profoundly unnecessary for any reason other than to motivate scenes of soap opera psychology.

The closing credits tell us the movie is based on the true story of “Shirl and Barbara Jennings, now living in Atlanta.” My guess is that their story inspired the scenes that feel authentic, and that countless other movies inspired the rest. Certainly the material would speak for itself, if the screenplay would let it: Every single plot point is carefully recited and explained in the dialogue, lest we miss the significance. Seeing a movie like this, you wonder why the director, Irwin Winkler, didn’t have more faith in the intelligence of his audience. The material deserves more than a disease-of-the-week docudrama simplicity.

Footnote: For a contrast to the simplified melodrama of “At First Sight,” see “Hilary and Jackie,” which examines relationships and handicaps in a more challenging and adult way.