You can sense the love of a daughter for her parents in every frame of “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries.” It’s brought into the foreground only in a couple of scenes, but it courses beneath the whole film, an underground river of gratitude for parents who were difficult and flawed, but prepared their kids for almost anything.

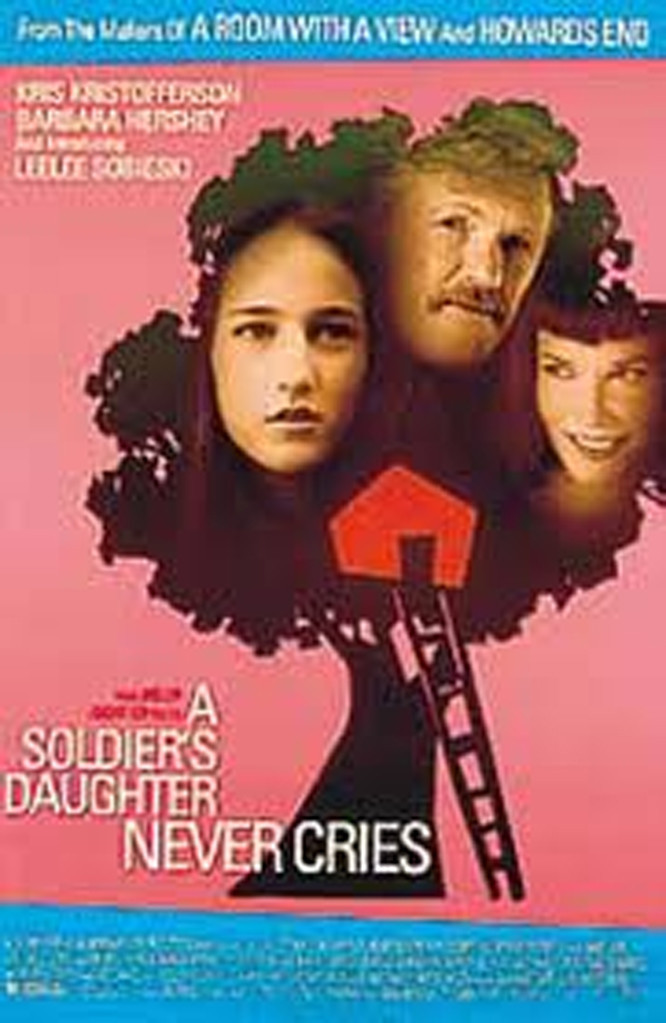

The movie is told through the eyes of Channe, a girl whose father is a famous American novelist. In the 1960s, the family lives in Paris, on the Ile St. Louis in the Seine. Bill Willis (Kris Kristofferson) and his wife, Marcella (Barbara Hershey), move in expatriate circles (“We’re Euro-trash”), and the kids go to a school where the students come from wildly different backgrounds. At home, dad writes, but doesn’t tyrannize the family with the importance of his work, which he treats as a job (“typing is the one thing I learned in high school of any use to me”). There is a younger brother, Billy, who was adopted under quasi-legal circumstances, and a nanny, Candida, who turns down a marriage proposal to stay with the family.

All of this is somewhat inspired, I gather, by fact. The movie is based on an autobiographical novel by Kaylie Jones, whose father, James Jones, was the author of From Here to Eternity, The Thin Red Line and Whistle. Many of the parallels are obvious: Jones lived in Paris, drank a lot and had heart problems. Other embellishments are no doubt fiction, but what cannot be concealed is that Kaylie was sometimes almost stunned by the way both parents treated her with respect as an individual, instead of patronizing her as a child.

The overarching plot line is simple: The children become teenagers, the father’s health causes concerns, the family eventually decides to move back home to North Carolina. The film’s appeal is in the details. It re-creates a childhood of wonderfully strange friends, eccentric visitors, a Paris that was more home for the children than for the parents and a homecoming that was fraught for them all. The Willises are like a family sailing in a small boat from one comfortable but uncertain port to another.

The movie was directed by James Ivory and produced by Ismail Merchant, from a screenplay by their longtime collaborator, the novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. She also knows about living in other people’s countries, and indeed many of Ivory’s films have been about expatriates and exiles (most recently another American in France, in “Jefferson in Paris”). There is a delight in the way they introduce new characters and weave them into the family’s bohemian existence. This is one of their best films.

Channe and young Billy are played as teenagers by Leelee Sobieski and Jesse Bradford. We learn some of the circumstances of Billy’s adoption, and there is a journal, kept by his mother at the age of 15, which he eventually has to decide whether to read. He has some anger and resentment, which his parents handle tactfully; apart from anything else, the film is useful in the way it deals with the challenge of adoption.

Channe, at school, becomes close friends with the irrepressible Francis Fortescue (Anthony Roth Costanzo), who is the kind of one-off original the movie makes us grateful for. He is flamboyant and uninhibited, an opera fan whose clear, high voice has not yet broken, and who exuberantly serenades the night with his favorite arias. We suspect that perhaps he might grow up to discover he is gay, but the friendship takes place at a time when such possibilities are not yet relevant, and Channe and Francis become soul mates, enjoying the kind of art-besotted existence Channe’s parents no doubt sought for themselves in Paris.

The film opens with a portrait of the Willises on the Paris cocktail party circuit, but North Carolina is a different story, with a big frame house and all the moods and customs of home. The kids hate it. They’re called “frogs” at school. Channe responds by starting to drink and becoming promiscuous, and Billy vegetates in front of the TV set. Two of the best scenes involve a talk between father and daughter about girls who are too loose, and another, after Channe and a classmate really do fall in love, where Bill asks them if they’re having sex. When he gets his answer, he suggests, sincerely, that they use the girl’s bedroom: “They’re gonna do it anyway; let them do it right.” “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” is not a textbook for every family. It is a story about this one. If a parent is remembered by his children only for what he did, then he spent too much time at work. What is better is to be valued for who you really were. If the parallels between this story and the growing up of Kaylie Jones are true ones, then James Jones was not just a good writer but a good man.