There is a pounding that starts inside the heads of certain kinds of people when they’re convinced they’re right. They know in theory all about being cool and diplomatic, but in practice a great righteous anger takes hold, and they say exactly what they think, in short and cutting words. Later they cool off, dial down, and vow to think before they speak, but then the red demon rises again in fury against those who are wrong or stupid–or seem at the moment to be.

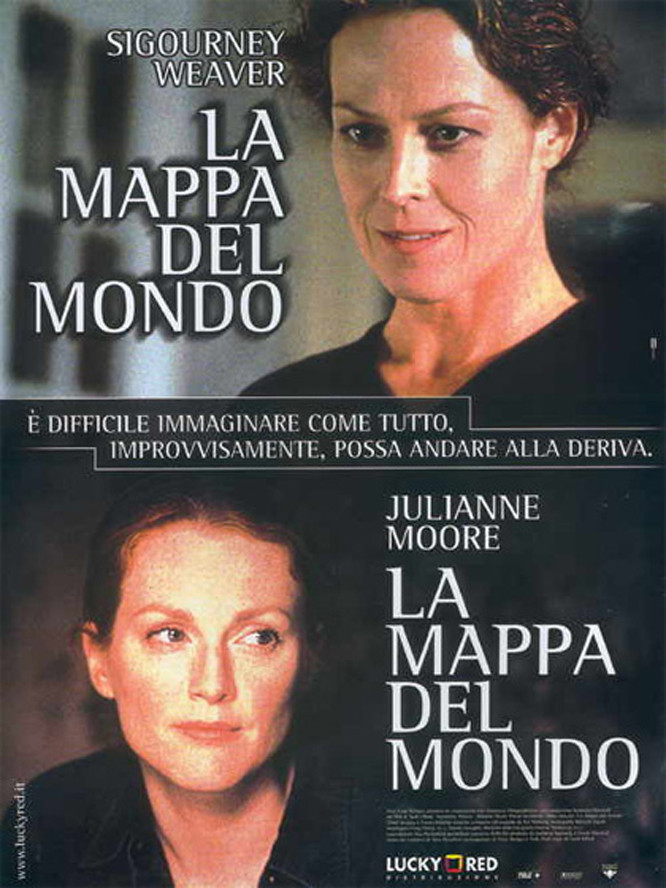

Alice Goodwin, the Wisconsin farm woman played by Sigourney Weaver in “A Map of the World,” is a woman like that. She has never settled comfortably inside her own body. She is not entirely reconciled to being the wife of her husband, the mother of her children, the teacher of her students. She is not even sure she belongs on a farm. You sense she has inner reservations about everything, they make her mad at herself, and sometimes she blurts out exactly what she’s thinking, even when she shouldn’t be thinking of it.

This trait leads to a courtroom scene of rare fascination. We’ve seen a lot of courtrooms in the movies, and almost always we know what to expect. The witnesses will tell the truth or lie, they will be effective or not, and suspense will build if the film is skillful. “A Map of the World” puts Alice Goodwin in the witness box, and she says the wrong thing in the wrong way for reasons that seem right to her but nobody else. She’d rather be self-righteous than acquitted.

This quality makes her a fascinating person, in one of the best performances Weaver has given. We can’t take our eyes off her. She is not the plaything or the instrument of the plot. She fights off the plot, indeed: The movement of the film is toward truth and resolution, but she hasn’t read the script and is driven by anger and a deep wronged stubbornness. She begins to speak, and we feel enormous suspense. We care for her. We don’t want her to damage her own case.

The plot involves her in a situation that depends on two unexpected developments, and I don’t feel like revealing either one. Neither one is her fault, morally, but bad things happen all the same. She’s smart enough to see why she’s not to blame for the first event, but human enough to feel terrible about it, anyway. And the second development is sort of a combination of the first, plus her own big mouth. Her family is terrified. Her husband doesn’t know what to make of her, and her kids don’t have the comfort of thinking of their mom as an innocent in an unfair world, because she doesn’t act like a victim–she acts like a woman who plans to win the game in the last quarter.

There are good performances all through the movie, which was directed by Scott Elliott and written by Peter Hedges and Polly Platt, based on Jane Hamilton’s popular novel. David Strathairn plays Howard, Alice’s husband, and Julianne Moore and Ron Lea play their farm neighbors–just about their only friends. When Alice spends time in prison, she gets a hard time from an inmate (Aunjanue Ellis), who senses (correctly) that this woman may have dug her own grave. And there is a small but crucial role for Chloe Sevigny, who in several recent movies (“Boys Don't Cry,” “julien donkey-boy” and the upcoming “American Psycho“) shows an intriguing range. As for Julianne Moore, see Stanley Kauffmann’s praise in a recent New Republic review, where he finds her grief “a small gem of truthful heartbreak.” The movie is not tidy. Like its heroine, it doesn’t follow the rules. It breaks into parts. It seems to be a family story, and then turns into a courtroom drama, and then into a prison story, and there is intercutting with romantic intrigue, and there aren’t any of the comforting payoffs we get in genre fiction. I’m grateful for movies like this; “Being John Malkovich” and “Three Kings,” so different in every other way, resemble “A Map of the World” in being free–in being capable of taking any turn at any moment, without the need to follow tired conventions. And in Sigourney Weaver, the movie has a heroine who would be a lot happier if she weren’t so smart. Now there’s a switch.