The films of Tyler Perry have been proving themselves critic-proof since his 2005 debut feature “Diary of a Mad Black Woman.” And yet outlets such as this one keep assigning writers to review them. Partially because it’s what they do. But he has always been a creator who demands critical interest. The populist appeal of the work, its sometimes-strident quasi-evangelical moralism, its occasional theatricality (which illuminates Perry’s artistic roots); it’s all worth considering. Even when the work doesn’t satisfy certain expectations.

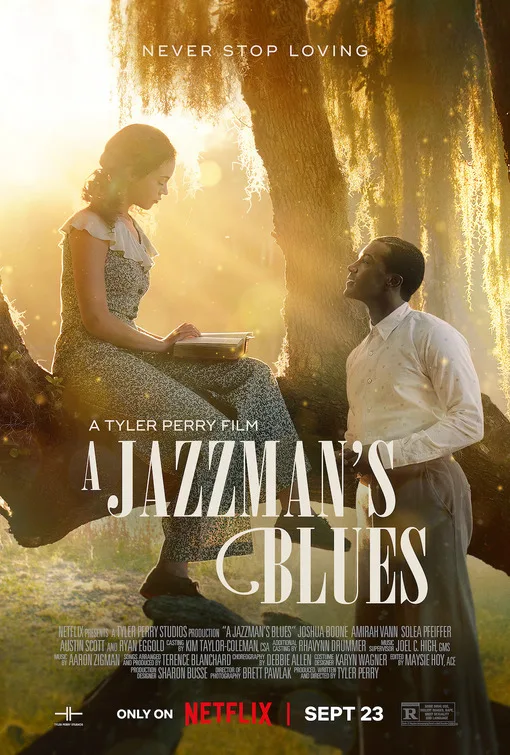

Perry’s canny moves into the Hollywood mainstream via acting roles in newsworthy pictures ranging from “Gone Girl” to “Don’t Look Up” may have expanded the audience for his directorial work. And with his recent deal with Netflix, that directorial work has gone into new territory. His new picture, “A Jazzman’s Blues,” in which Perry does not appear, is from a script he says he wrote 27 years ago. On a recent appearance on “The Today Show,” Perry said, “I had to be strategic in what I was doing before, so I had to make sure I had a hit after a hit after a hit, so this one I just wanted to take my time and do it at the right moment.” Telling this story now, he says, became imperative as Perry witnessed contemporary book banning, distortion of Black history, “the homogenizing of slavery and Jim Crow” being one aspect of that which troubles him particularly.

From its very opening shots “A Jazzman’s Blues” shows that Perry has developed a genuine fluency as a filmmaker. The story’s setup is a frame, something right out of John Grisham maybe: sometime in the not-too-distant past, a Black woman watches a political pitch on television from the current Attorney General of Hopewell, Georgia, disdaining his racist views. Nonetheless, this old woman soon turns up at the man’s office, bearing a sheaf of letters and making a request. “You want me to look into a murder that happened over 40 years ago,” says the bureaucrat in disbelief. (As it happens the woman knows everything but intends the query as a lesson.) We flashback to 1937, and a rural Black community, and a lot of unhappiness.

The sensitive, tentative young man nicknamed Bayou (Joshua Boone) comes from a family of itinerant musicians. Including a father who huffs “Boy got to learn to get tough at some point.” The fact that Boone can sing but can’t play makes him an object of contempt for that father and for Boone’s brother Willie Earl (Austin Scott); with the latter there’s a real Cain and Abel vibe going on. Good fortune smiles on Boone in the form of LeAnne (Solea Pfeiffer), an outcast of a different sort. “I can still smell the lavender and the moonshine,” Boone avers in one of his letters. For a short time the two share a secret love. She teaches him how to read. But she’s snatched away by her avaricious mother who takes her up North and marries the girl, who can pass for white, to a well-off-Caucasian. 1947 brings an unfortuitous reunion of Bayou and LeAnne. “What is wrong with these negroes down here?” asks a member of LeAnne’s new people when Bayou is so forward as to take a seat in a white family’s kitchen. “Oh, we keep ‘em in line,” responds a representative of local law enforcement.

After a few twists and turns, and a not-secret-enough return to amorous activities between Bayou and Leanne, Leanne’s mom actively tries to get Bayou lynched. The issue thus forced, Bayou flees to the North. (He had actually been doing okay at the roadhouse founded by mom Hattie.) And as time goes on Bayou’s singing starts paying off. He is the jazzman of the title, but his success as a singer doesn’t compensate for the pain of losing his love. The tensions between him and trumpet-playing Willie Earl increase, especially as Willie Earl turns to heroin. And then there’s the matter of a baby. And of an ill-fated visit back home.

While the direction maintains a smooth and often tense tone (while sometimes serving up peculiar juxtapositions, like a childbirth intercut with a “jungle”-themed nightclub dance), Perry’s script hits a lot of notes right on the nose (there’s a white jazz booker who’s a Jew who escaped the Holocaust), and why not. It also has a lot of astute observations on the psychology of racism. A scene in which LeAnne, living the life of a white woman, upbraids a dark-skinned “domestic,” is genuinely jarring. The star-crossed lovers of the movie are caught in a loop of American racism, and their existences are defined by a desire for escape. Escape is a romantic notion, and this movie has its romantic side, for sure. But underneath the trappings, including a lush score by Aaron Zigman and the near-dreamy cinematography of Brett Pawlak, there’s a genuine anger about the utter senselessness of the hate that’s defined our history.

Some critics have compared Perry to Douglas Sirk. This is a fallacious analogy that, ultimately, is a kind of insult to both filmmakers. Each of these storytellers exercise social consciousness in styles that are entirely distinct from each other. And “A Jazzman’s Blues” proves that when Perry applies himself in a particular fashion, his work can stand entirely on its own.

On Netflix today.