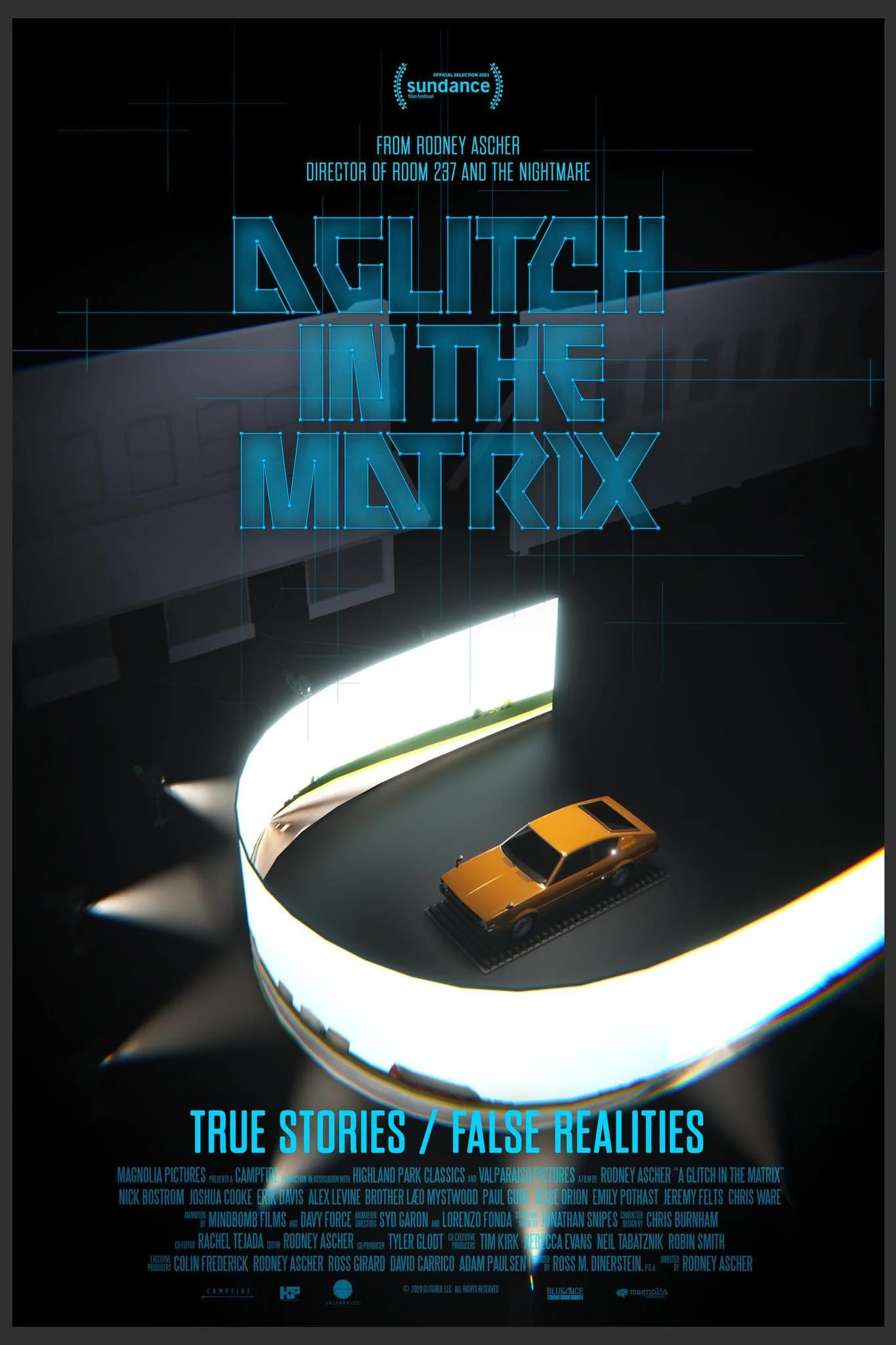

Rodney Ascher’s documentaries dream of something bigger than just sharing information—they aim to permanently rewire your brain. His debut feature “Room 237” broke down the wildest hidden messages within Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining,” so that you’ll never see that classic the same way again. His follow-up documentary, “The Nightmare,” focused on the phenomenon of sleep paralysis, with the menacing trick being that watching a movie about such a concept could indeed pass it on to viewers. “A Glitch in the Matrix” is his most ambitious rabbit hole yet, but it also proves to be his most novel, and least playfully convincing.

There are people out in the world who believe that we, as human beings, are living in a simulation. That we are avatars in a larger video game being played by something else, that coincidences in our lives are glitches as some part of construction, and that we can spot the seams of this world if we pay close attention. To these people, who base their entire life perspective on something they call “simulation theory,” movies like “The Matrix” and “The Truman Show” are more truthful to the big picture, and are texts that can be be used for reference. The same goes for the works of Philip K. Dick and their adapted movies, as Dick was a large proponent of the theory who spent a long time trying to understand his own thoughts about it.

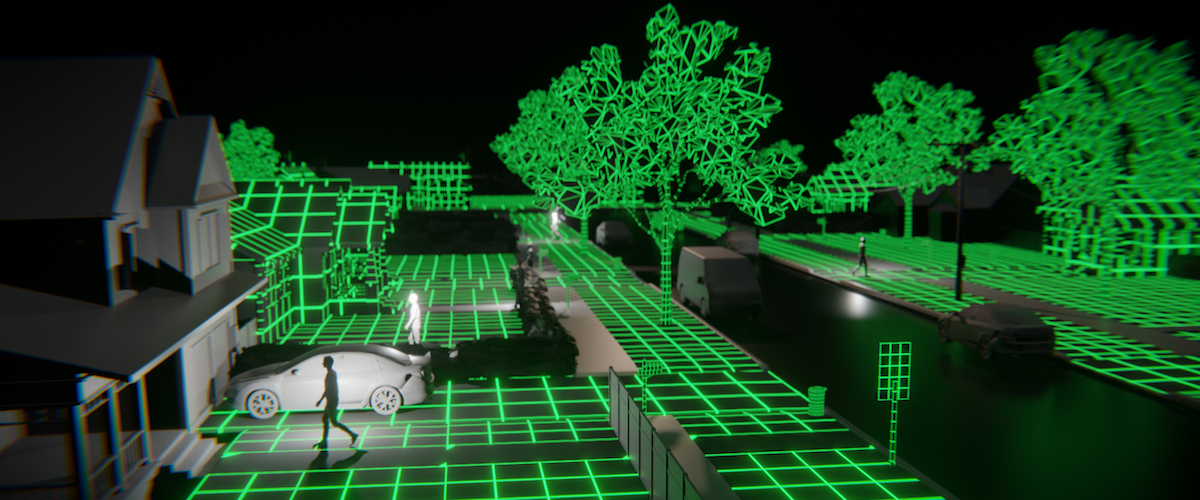

It’s unclear watching the film whether Ascher believes all of this, but it’s more that he wants to invest in this theory and pass it along. He becomes a type of interpreter for this point-of-view, using his encyclopedic pop culture knowledge to accompany elaborate different theories and relay the experiences of his select “witnesses” through gripping, trippy animation sequences. Accompanying the words of interview subjects presented as cartoonish sci-fi avatars (with shields, sharp teeth, space suits etc.,) they relay beliefs of how maybe we are just a brain in a lab, a body in a sea of pods; these talking-avatars are often well-spoken, and the documentary is in turn informative and entertaining about a concept your possible overlords may have not wanted you to consider. Ascher uses an impressive, vivid trove of pop culture clips to further illustrate the documentary’s colorful tangents, capturing our existence as a scene in “Starship Troopers,” or “Star Wars,” or a “GTA V” “funny fails” video, the latter involving 100 monotonous people being pushed off a platform in the sky by a bulldozer.

I believe that this type of skepticism is healthy. If you’ve ever lost an item that seemed to just vanish into thin air, you might too have that feeling, that no other explanation is possible than some gap in some reality swallowed up my damn mailbox key. But “A Glitch in the Matrix” does not, until much later in the movie, get behind the true type of antisocial mindset it takes to deeply see the world as a type of false reality, and the human beings around you as certain products of it. There’s a vital sociological element that’s missing about how life experience could cause someone to view existence with such a lens, and Ascher’s documentary can feel like an erratic, however meticulously illustrated “explainer” YouTube video without it.

Later on, Ascher focuses on the danger of this psychology with regards to Joshua Cooke, a super-fan of “The Matrix” who committed homicide and says over a phone call interview that he was surprised to see the violence he created not like that of the Wachowskis’ film. “A Glitch in the Matrix” goes even more out of control by recreating the experience (as if walking through a video game level, but with no bodies) as Cooke’s recollection guides us. It’s a weirdly indulgent moment that hardly adds to our understanding of the film’s larger points aside from highlighting their obvious craven side effects. Instead it prods more at an underlying idea in “A Glitch in the Matrix” that video games and movies have both given us a language to talk about these things—giving us concrete examples, like “The Matrix”—and also can be blamed as an influence on people dehumanizing others, and in some cases acting out with violence.

Within the film, Ascher has essentially also created a great video essay on Philip K. Dick, and how the simulation theory appeared in adapted films like “Total Recall,” “Minority Report,” and more. Dick had his own visceral experience and reflected upon it in different novels, informing his depiction of authority and technology—details that are succinctly shown in Ascher’s documentary. The footage of a slightly self-conscious but stern Dick reading off a speech in France about his belief in it is about the closest the doc gets to a full idea of the complex thinking behind it, and how it affects the person who carries such a philosophy.

“A Glitch in the Matrix” is so much about conveying its big idea that it misses the smaller parts—it oddly seems limited in its overall mission, documenting this mix of philosophy, sci-fi, and religion without helping us understand its believers. And yet it does inspire a healthy, atypical curiosity, not so much about whether we are indeed living in a simulation, but as to who else out there also thinks that their keys are missing due to something larger than human error.

This review was filed out of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. The film will be available everywhere February 5.