EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is part of of “MZS 30,” a series of reprints that amount to a cross-section of Matt Zoller Seitz’s thirty years as a film critic. They are reprinted in their entirety with introductions contextualizing them in their time and place, and critiquing them from the standpoint of where the writer is today.

Thirty years ago this week, the firefighting action movie “Backdraft” opened. I had just started my first professional journalism job at Dallas Observer, a weekly newspaper in my hometown of Dallas. “Backdraft” was the first paid review I ever wrote.

At the time, I was employed as a calendar editor at Dallas Observer for $250 a week. There were no benefits save for the experience itself—which, as it turned out, was priceless. My main job at the Observer was rewriting press releases to give them a bit of sass and entice people into attending the events described therein. I also got to do other kinds of writing, including reported news stories and features, but until this piece got published, I hadn’t been able to convince my bosses to let me review movies for them.

I guess in theory I was still a college student. I got the calendar editor job in April, 1991, shortly before I failed to graduate from SMU on time as scheduled, thanks equally to my work as a student journalist and filmmaker (which I cared about far more deeply than any of my classes) and my fondness for alcohol and marijuana (ditto). Despite the last dregs of my scholarship money running out, I would end up graduating a year later, paying my tuition by writing additional pieces for the newspaper beyond the duties I was already under contract for.

The lead film critic of Dallas Observer was Southern Methodist University English professor John Lewis, a marvelous writer who invariably found ways to work in references to whatever literature he was teaching in his classes. The week that Martin Scorsese’s remake of “Cape Fear” opened, Lewis compared it to Flannery O’Connor’s “The Violent Bear It Away,” a book he was teaching in “Southern Fiction, 1900 to the Present,” a course I just happened to be enrolled in; how strange and wonderful it was to read that review in a booth at Snuffer’s, my favorite burger joint near campus, while my copy of the O’Connor novella sat on the table right next to my basket of cheddar fries. Other critics (including The Houston Post‘s Joe Leydon) floated in and out of the second film review slot, but John was the star.

By the time I started at the paper I’d been reviewing movies (and writing features and editorials) for The Daily Campus, SMU’s student newspaper, for three years, and had won various student journalism awards. After weeks of lobbying my section editor to let me review films, she gave me “Backdraft” to shut me up.

I think I did a decent job, although it’s clear in retrospect that I overrated the quality of the film, or failed to maintain any intellectual distance from it. It was a good movie with solid performances, some directorial flourishes, and a couple of fresh script ideas, but it hardly merited the enthusiasm with which I described it here. We didn’t assign star ratings at Dallas Observer, but if we did, I’d have to say that this was two-star quality writing applied to a three-star motion picture that got puffed up to implied four-star status. I was so excited to be doing the job that I got carried away.

I still do that. All the time.

“High-Tech Boyhood Fantasy”

Ron Howard’s firefighting epic “Backdraft” is an old-fashioned valentine to apple-pie heroism

Dallas Observer, May 23-29. 1991

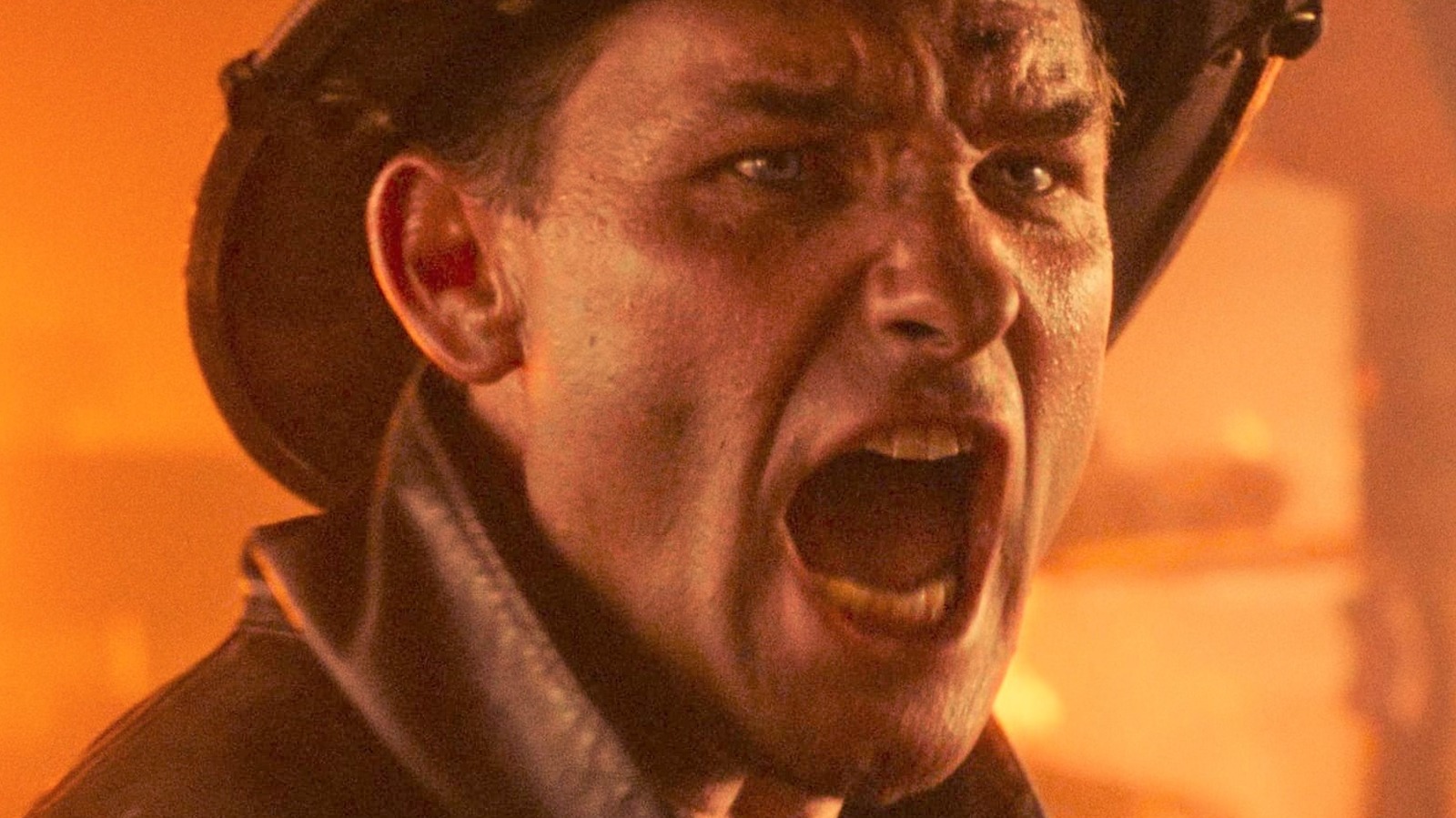

If you ever wanted to be a firefighter when you were little, “Backdraft” will cure you of it. The flame-resistant protagonists of Ron Howard’s latest film take an astonishing amount of punishment. To watch this movie, you’d think there was only one ladder truck serving all of Chicago and every blaze was a Chernobyl-level disaster. “It’s not like any other job,” says super-firefighter Stephen McCaffrey (Kurt Russell). “On this job, if you have a bad day, somebody dies.”

Not to say “Backdraft” is unglamorous, though—far from it. This movie harps on the dirty, dangerous aspects of the job in punishing detail but never lets you forget these guys are heroes. The slow-motion sainthood lavished on Russell and company is absolutely epic—so many firemen emerge from smoke clouds toting squealing women and children that it starts to feel like you’re watching a laserdisc that got stuck on the same scene—but such excess is forgivable when rendered with the conviction and skill demonstrated here. “Backdraft” is the “Top Gun” of firefighting, but in a good way; you can bake in its Norman Rockwell tableaux and inhale its clichés like bottled oxygen, but it won’t leave a morally questionable ash all over you when you exit the theater.

The plot elements seem assembled for maximum audience rooting potential. In a ghastly flashback to an incident that made national headlines 20 years earlier, the McCaffrey brothers watch their firefighter father perish while rescuing a child (the father, oddly, is played by Kurt Russell in dinner theater “old age” makeup). The brothers drift apart. Stephen McCaffrey follows in the old man’s sooty footsteps, collecting awards and citations, but he’s a troubled hero. His wife Helen (Rebecca De Mornay) grows weary of his psychotic devotion to duty and divorces him, and Stephen’s self-righteousness alienates his younger brother Brian (played with quiet authority by William Baldwin). Brian is a screwup drifter who chose firefighting as a last resort; he must prove himself on the job to earn his older brother’s respect and capture the affections of his childhood sweetheart, Jennifer (Jennifer Jason Leigh). It doesn’t take a MacArthur Foundation genius grant to figure out that by the story’s end, Stephen will make peace with his wife, Brian will win Jennifer’s love, and the McCaffrey brothers will booze, curse, and brawl their way back into each other’s arms.

For a while, you may wonder how “Backdraft” will beat the hobbling plot flaw of Steven Spielberg‘s “Always,” another big-budget firefighting picture awash in old-movie nostalgia: how to convince the audience to root not against a villain, but an element. Howard and screenwriter Gregory Widen do this two ways.

First, our heroes must contend with a possible arsonist who may or may not be setting the film’s most explosive blazes. Trailing the elusive firebug is arson investigator Donald Rimgale (Robert DeNiro), a gruff veteran who lights unfiltered cigarettes on smoldering rubble and fixes meddling bureaucrats with the stare of a hard-assed shop teacher. Brian McCaffrey quits riding the big red trucks to escape his brother’s domineering attention; once he starts poking through charred ruins with Rimgale, the story really gets cooking, so to speak. Arson investigation is more cerebral and less testosterone-poisoned than firefighting, and De Niro and Baldwin’s wizard/disciple interplay has real charm. Their dogged pursuit of the secrets of arson lifts “Backdraft” right when it starts to get repetitive.

The second, more impressive trick is making fire a character with its own personality and psychology. As characterized by the veterans loping through “Backdraft,” fire is a living thing, and to defeat it you must understand its allure and learn to think like it. This loopy anthropomorphism is sold to us via flame-hugging camerawork, frightening stunts, and the imaginative use of visual effects. Many times, a group of men will be trapped in a burning shaft or a crumbling room, walled in by flame, only to see it slither mysteriously back into a crack or crevice, then reappear suddenly in the damnedest places. It even has its own sound design: a low, wheezing rumble-moan, like the mighty bellows-lungs of a fire-breathing mythological beast. This creature inhales and exhales in repose, then ramps up to a searing roar when it decides to stop hiding and burst into open air. Fire is the dragon, and the firefighters are the errant knights trying to find it and neutralize it. The shock and suspense in these scenes rivals “Aliens” for sheer intensity.

Clearly, fire is bigger and more mysterious than the human mind can comprehend, although one man comes close: Donald Sutherland, face half-baked by burn scars, as a Hannibal Lecter-ish arsonist that Brian and Rimgale visit behind bars for hints on how to pursue their case. With grandfatherly amusement and giggly hamminess, Sutherland gooses “Backdraft” out of reverence and into the realm of movie magic. Behind his goofy stare and mumbo-jumbo lore, you can almost see the Spirit Of Fire.

“Backdraft” is far from flawless: there are too many shots of fire trucks racing to put out monstrous blazes, too much neo-Yoda wisdom, and too many closeups of fire damaged bodies (one firefighter suffers a wound so gratuitous it may provoke laughter from some viewers: a fall splits his belly open, and whatever that organ is that pops out, it beats like the Grinch’s heart on Christmas Day). But the repetitiveness wedges you into the characters’ mindsets, and after a while, the mix of terror and nonchalant righteousness displayed by McCaffrey and company becomes understandable. “Backdraft” captures the spectacle of America’s last unstained heroes doing their jobs with gusto: saving babies, extinguishing blazes, and facing private demons with smoke-stained apple pie grins. It’s a high-tech childhood fantasy, filmed in Super Hero-Vision. You can laugh at its piousness, but you’d have to be an arsonist to resist its aura of dread and joy.