Sometimes there are movies that strike you in a certain way, that haunt your memory and provide some of the terms with which you view your own life. For Steven Spielberg and Richard Dreyfuss, “A Guy Named Joe” must have been a movie like that. Released in 1944, it starred Spencer Tracy as a pilot who dies in combat and is assigned by heaven to return to earth to inspire the younger pilot (Van Johnson) who will take his place. The kicker is that Tracy also has to stand by helplessly and watch while Johnson falls in love with Tracy’s girlfriend (Irene Dunne).

Dreyfuss says he has seen “A Guy Named Joe” at least 35 times.

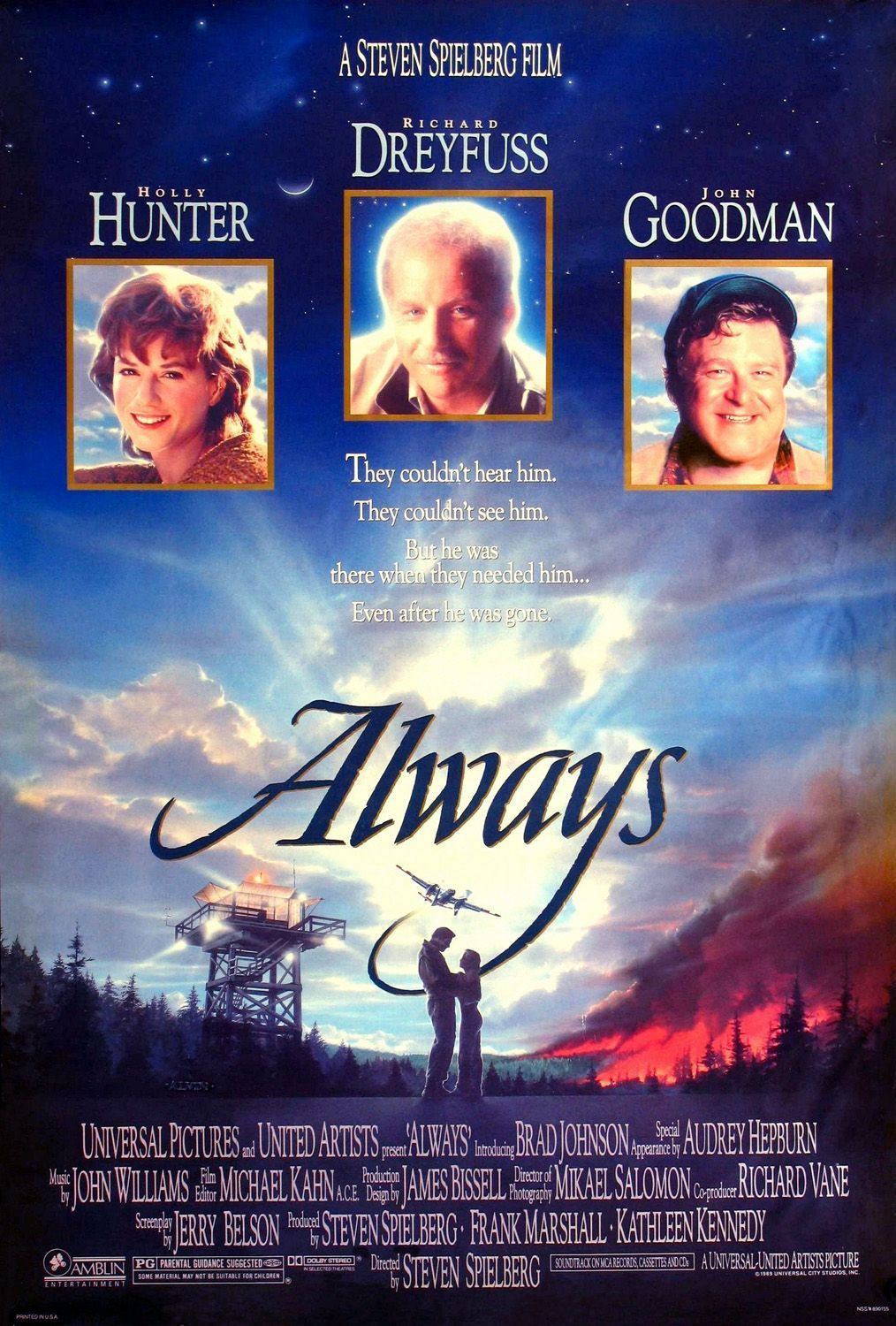

Spielberg watched it again and again on the late show when he was a kid, and it was one of the films that inspired him to become a movie director. When Spielberg and Dreyfuss were making “Jaws” in 1974, they quoted individual shots from the movie to each other – and finally, in 1989, they got to make it themselves. The remake is called “Always,” and it takes place now instead of then and the pilots are fighting forest fires instead of enemy planes, but the basic ideas are all still in place. They do not, unfortunately, add up to much; this is Spielberg’s weakest film since “1941.” Dreyfuss stars as a guy named Pete, who fights fires in the Pacific Northwest and spends his off-duty hours romancing a cute forest service air traffic controller (Holly Hunter). Pete is a guy who likes to take chances, and there are cliff-hanging scenes early in the movie where he runs out of gas and glides to a landing and when he nearly crashes into a blazing forest fire. His best pal is a pilot named Al (John Goodman), who also likes to take chances and crashes into some burning trees one day, setting his plane on fire. Pete the daredevil goes into a dive and puts out the fire on Goodman’s plane by dumping chemicals all over it, but then Pete’s plane crashes and he wakes up in a heavenly forest grove presided over by an angel (Audrey Hepburn).

That sets up the second act of the movie, in which poor Pete has to come back to earth and be an invisible inspiration for the youngster (Brad Johnson) who has replaced him. And he has to watch, impotently, as the kid and Pete’s former girl fall in love. There is a lot of pathos to be exploited here somewhere, but I didn’t feel much.

My reaction to “Always” resembled the critic James Agee’s merciless review of the 1944 film, which he admired less than Spielberg and Dreyfuss. “Joe’s affability in the afterlife is enough to discredit the very idea that death in combat amounts to anything more than getting a freshly pressed uniform,” he wrote, adding that Tracy “is so unconcerned as he watches Van Johnson palpitate after Irene Dunne that he hardly bothers to take the gum out of his mouth.” One of the problems with “Always” is that the cause itself seems less urgent. It’s one thing to sacrifice your life for a buddy in combat and quite another to run unnecessary risks while fighting forest fires. Another problem seems to stem from Spielberg’s love of spectacular special effects. The airplanes in this movie – World War II surplus bombers, modified to dump chemicals on fires – seem to crash and bludgeon their way through acres of blazing treetops. You’d think a collision with just one of these trees would cause a plane to crash, but the firefighters in “Always” mow through the woods like airborne Lawnboys. The effects are so spectacular, they’re not believable. All the movie’s risks seem to be the same – laughable.

The best casting in the movie is Hunter, as the air traffic controller, bringing some of the same urgency and hard-bitten impatience that made her right for “Broadcast News.” She has a no-nonsense approach that works better than the derring-do and unflappability of Dreyfuss and Goodman. The scenes where the angelic Dreyfuss watches while Hunter and Johnson fall in love are the most awkward in the film; the screenplay gives Dreyfuss flip lines like “That’s my girl, pal!” when maybe a hurt look or a silent turn away would have been more effective.

The film’s most curious quality, given the fact that it was directed by Spielberg, is a lack of urgency. Even though pilots are flying into the jaws of hell, they have an insouciance, a devil-may-care attitude, that undermines the drama. The feeling of the film is more 1940s than 1980s, which is no doubt what Spielberg was hoping for, but I’m not sure it works. Some of the dialogue seems dated, too, and a lot of it sounds “written” instead of “spoken” – as if these guys learned to talk by studying old pulp magazines. The result is a curiosity: a remake that wasn’t remade enough.