“Sharp Corner” is about a couple with a young son who leave the city and move into a house in the country. The price was favorable. On their first night, they find out why. The house is maybe a hundred meters away from a tight turn in a two-way road that cuts through tall fields. There’s a sign before the turn, warning drivers that it’s sharp. But the sign is obscured by vegetation, and even if it wasn’t, speeding drivers still might not be able to slow down in time to prevent a wreck.

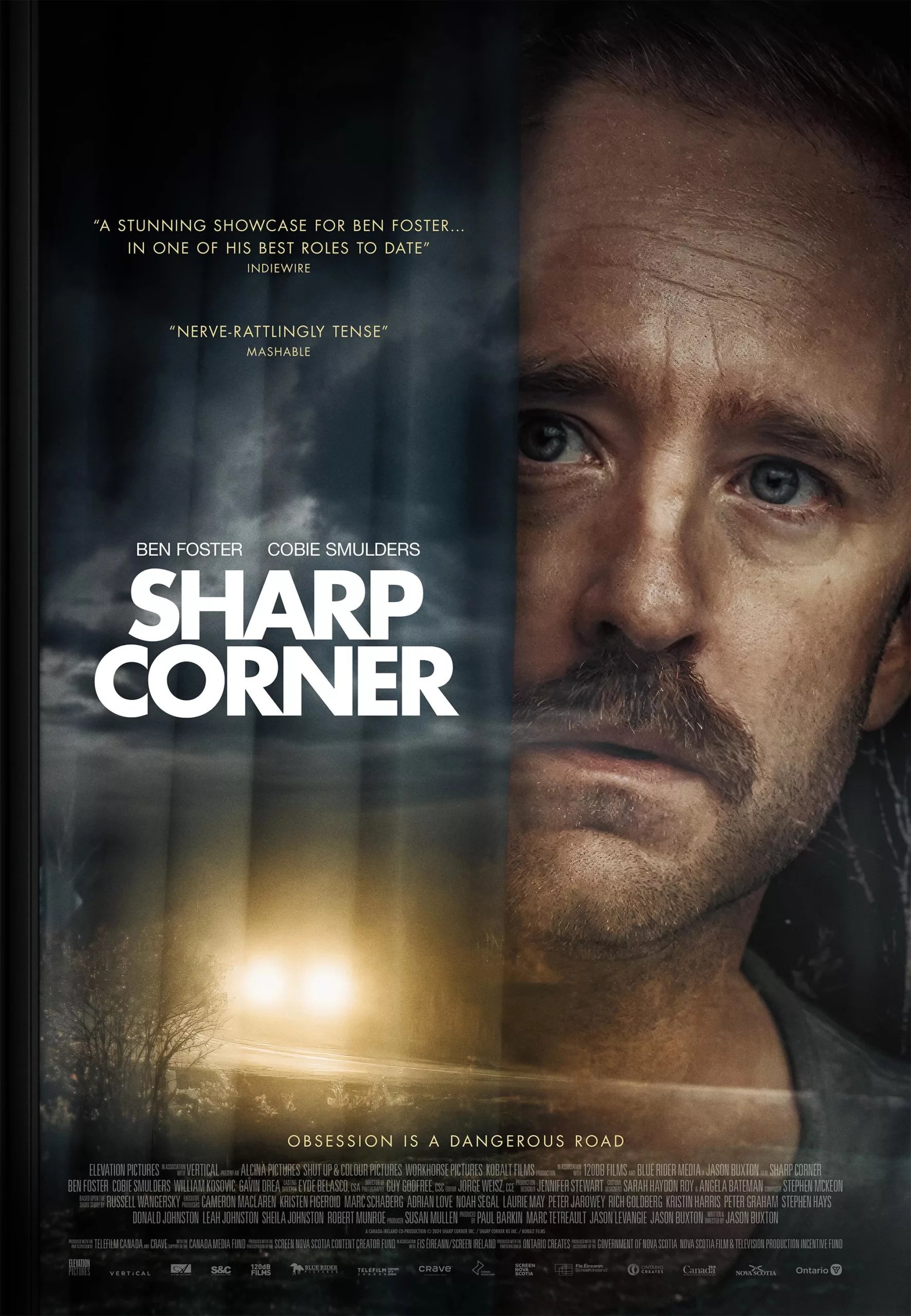

The first crash traumatizes the family. Then there’s another. The corner is a death trap. Each crash or near-miss drives the family further apart and destroys the sense of safety that a home is supposed to confer. The father, Josh McCall (Ben Foster), becomes obsessed with the idea of training to prepare for the next crash so he save anyone who survives. The mother, Rachel (Cobie Smulders), endures the stress as long as she can, then starts agitating to sell the house and move someplace else. The son, Max (William Kosovic), starts the story as a well-loved, privileged little boy, sweet if a tad spoiled, but he internalizes the violence as well, to the point of using toys to re-stage crash scenes in miniature.

You might be thinking, “It sounds very thoughtful and dramatic and I’m sure it’s a good movie, but no thanks.” That’s understandable. This movie goes to very dark places, especially as the focus tightens on Josh and we watch him change before our eyes, and not in a comforting way. The impulse to want to try to save everyone is recognizably human and the sign of a person who—whatever other flaws they possess—has redeeming qualities and could be a hero under certain circumstances. The main problem for Josh is that he starts trying to build his entire life around the possibility, or inevitability, of the next crash, attending CPR classes, inquiring about buying his own training dummy, and attending the funeral for one of the victims.

“Sharp Corner” analyzes Josh’s transformation with a mix of empathy and scientific detachment. Foster’s performance anchors the character in plausible humanity. He always just seems like a guy who is going through something awful, rather than a sociological case study or a symbol of what ails modern man. The film is about a lot of things. One is what we do with the knowledge that death is coming for us and everyone we know, and we can’t anticipate or prevent it.

Foster, one of the most remarkable actors in modern film, is brilliant in what might be his most unexpected performance in years. He’s got a look that makes him a perfect candidate for playing lethally violent men, whether flamboyantly vicious (“Alpha Dog”), righteously aggrieved (“Hell or High Water”), dutiful but wounded (“Leave No Trace”), or instinctively noble in ways that the character isn’t smart or self-aware enough to recognize (“Galveston”). The character’s driving impulse here is to heal rather than damage or kill, which puts this performance on a different wavelength than a lot of the others.

Another striking difference is that, despite all the crime thrillers he’s done, Foster is believable as a guy who may never have thrown a punch in his life. Josh has a potbelly and bad posture and an awkward walk. He’s losing his hair in front. He talks softly, with a bit of a whine. His calmness can seem judgmental. Something about him makes people think he’s self-regarding even when he isn’t. His politeness can read as tactical positioning. And sometimes it is.

Josh is genuinely disturbed by the boy’s death. Josh and Rachel throw a dinner for couples from the old neighborhood. Josh tells their guests about the homemade shrine at the curve honoring the victim of the first crash the family witnessed. We even saw him poring over social media posts while he was supposed to be working in his office. But Rachel chastises him after the dinner. She accuses him of trying to present himself as morally superior by launching into a depressing monologue what was supposed to be a lighthearted evening. She calls him “smug.” Is he? Or it it just the way he comes across?

Smulders matches Foster’s exactness and focus, though she begins to recede once Josh’s manic behavior accelerates and his choices become worse. In fairness, she doesn’t know how bad he feels because he’s hiding that from her, along with his EMT training equipment. Rachel loves Josh but is starting to think she can’t live with him. He’s messing up at work and making terrible choices while caring for their son. It can’t go on like this. Are they destined to split? These knowns and unknowns are all defined, or at least hinted at, but you have to pay attention to see them. Nothing is spelled out, even in therapy scenes.

This movie has some of the most specific and believable husband-wife exchanges you’ll ever hear. They aren’t especially clever or eloquent and aren’t trying to be. They just sound like people talking, in the way that these kinds of people would talk. They keep things at room temperature, mostly, unless things are really dire. They try not to yell. They want their son to feel nurtured, in a loving and calm environment. But their dialogue is filled with passive-aggressive digs that might not be recognized as such by anyone outside of the house, like when Josh picks Rachel up from work and she’s a few minutes late and he says maybe it’s time they “bite the bullet” and buy a second car, and she instantly replies, “Are you saying that because I’m a few minutes late?” He swears that he isn’t, but we know that he is.

Apart from its meticulous deconstruction of a family coming apart, “Sharp Corner” is memorable for its thoughtful compositions, which put a lot of information into each frame at different planes of distance and let us decide where to look. The camera moves a lot, but mostly slowly, and always for a reason: to reveal or conceal something, or fill us with anxiety. Guy Godfree’s cinematography has a mid-’70s American New Wave feeling. It’s rich and clear even in dark scenes, but never ostentatiously beautiful. Every shot is about making you feel as if you live in this little world. The geometry of the shots and the deployment of sound cues are so exact, and repeated with variations so purposefully, that you begin to feel as if you live in that house and know when things are OK and when trouble is brewing. The sound design is exceptional, reveling new insights as the story unfolds. After a while, you can tell by the sound of an approaching vehicle whether it’s going too fast.

Stephen McKeon’s score is melancholy, then mournful, then turns into a magnificent lament. Horns come in and get louder as the stakes rise and the situation becomes more dire. Howard Shore’s scores for David Cronenberg and Carter Burwell’s scores for the Coen Bros. hit our sensibilities in much the same way. What’s onscreen may be small in the greater scheme, at times comically wrongheaded, but the music finds grandeur in it, even becoming a sort of ironic requiem for people whose lives have been twisted and shattered—by their own hand, a twist of fate, or both.

Have you seen “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” Steven Spielberg’s movie about workaday Midwesterners haunted by encounters with UFOs and afflicted with visions of a miracle in the making? If not, please do. Odd as it may sound, “Sharp Corners” would make a fascinating double feature with it, not because the films exactly mirror each other (though Foster does resemble the Spielberg movie’s star, Richard Dreyfuss, from some angles, and there are scenes in both where an unhinged patriarch tries to convince his family not to drive off and leave him); but because both are about people who have something random and extraordinary happen to them not once but repeatedly, and respond by throwing themselves into all-consuming projects. Roy makes sculptures to clarify his visions. Josh takes a lifesaving class and starts practicing chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Both men stay up all night staring at a bend in the road, waiting for the lights to return.

This is a quiet classic. Every choice is just right.